One of the starkest dividing lines between the two main parties at Westminster is over climate - or at least that’s what both sides would have you believe.

Remember when rain-soaked Rishi Sunak fired the starting gun on the election standing outside No 10? He boasted about how his government had “prioritised energy security and your family finances over environmental dogma and our approach to net zero”.

Sir Keir Starmer, by contrast, talked about “harnessing Great British Energy to cut your bills for good” with the “largest investment in clean energy in our history”.

The smaller parties lay claim to having serious green credentials - the Lib Dems say tackling climate change is at the heart of a new industrial strategy, and the SNP says it is “proud to have the most ambitious legal framework for emissions reduction in the world”. The Greens and Plaid Cymru say climate is at the centre of their proposals and have promised to hold Labour to account if it wins the election.

Net-zero agendas

Labour has built much of its vision for the future around its energy plans. It claims the initial £8bn of public cash over five years it has pledged to its Great British Energy company will kick-start a process of industrial renewal, reviving the economy in the loosely termed Red Wall constituencies to deliver jobs as well as secure supplies of energy and lower bills.

The Tories have been attempting to characterise this as a return to state control. It is the job of entrepreneurs to take risks and pick winners, they say; when politicians try, it ends up costing ordinary people dear.

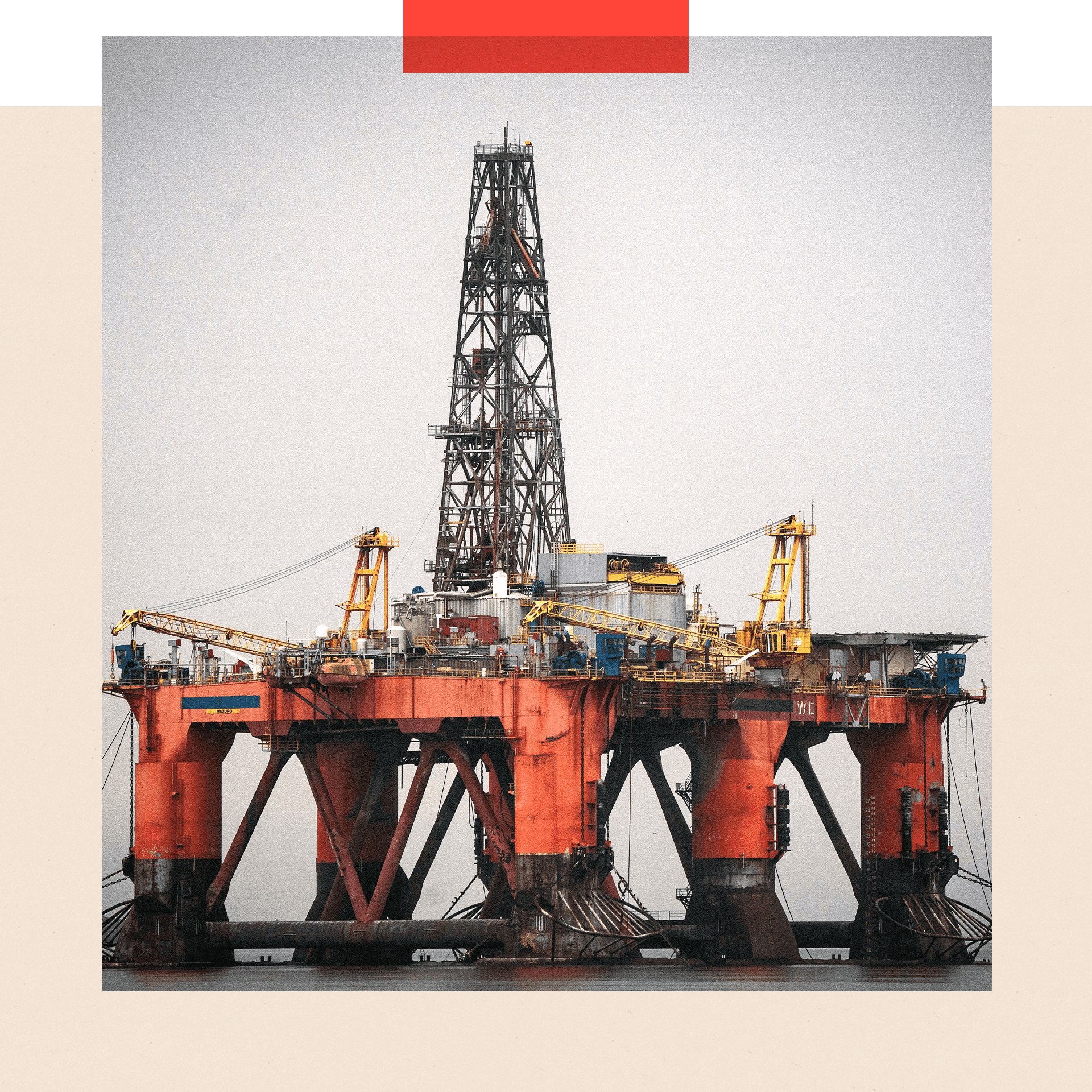

You can trust us to keep your energy bills low and protect the country from the whims of tyrants like Putin with new oil and gas from the North Sea, is the message from the Conservatives.

It sounds like there is an ocean of difference between the two main parties. But dig down into the detail of their policies and it’s a different story.

The core agenda on climate - getting the UK to net zero emissions by 2050 – has always been very much a cross-party project.

Labour introduced the Climate Change Bill in 2008 to make it a legal obligation for future governments to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050. Both parties wholeheartedly supported the proposal - just five MPs voted against it.

It was Theresa May’s government in 2019 that upped the target to 100% of emissions - net zero - supported again by a whopping cross-party majority. That is something that Energy Secretary Claire Coutinho must have forgotten when she warned against Labour’s “reckless net zero targets, external” in recent days. She was not yet an MP at the time of that 2019 vote.

Ms Coutinho has also been very critical of what she has called Labour’s “mad plans, external” to decarbonise the grid by 2030. Rishi Sunak has described the policy as “completely ridiculous”. Yet the Conservatives aim to ensure 95% of UK electricity will be low-carbon by 2030, with full decarbonisation following five years later. Squeezing out those last few percentage points of fossil fuel power will undoubtedly be the hardest, but these aren’t hugely different agendas.

And how about our vehicles? In September Rishi Sunak announced with great fanfare that his government was going to push the ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars back from 2030 to 2035. He made much less noise about the fact his government would be retaining the obligation on manufacturers to ensure 80% of car sales are electric by then. In that context, Labour’s plan to revert back to a 2030 ban doesn’t look that drastic.

On oil and gas, the Tories approved drilling on the controversial oil field, Rosebank, back in September. It is reckoned to be last large untapped field in the North Sea. The party claims that its plans to license other new oil and gas projects will help guarantee energy security – though Ms Coutinho conceded on BBC Breakfast back in November that it won’t necessarily lower bills.

Labour has said it won’t approve any new projects in the North Sea - an important symbolic gesture for the UK - but it has promised to honour all existing oil and gas licenses, including Rosebank. In Aberdeen last week, Starmer was at pains to emphasise that, under Labour, oil and gas will be part of the UK’s energy mix “for decades to come”.

And the list goes on. Both parties back a windfall tax on oil and gas companies until at least 2029, though the rates might differ by a few percentage points. Both parties say they support a massive expansion of solar power - the Tories want 70 gigawatts (GW) by 2035, Labour 50GW by 2030. Both parties want to see offshore wind continue to grow - the Tories want 50GW more by 2030, Labour 60GW, including 5GW of floating offshore wind.

There are some standout policy differences, however. A Labour government will not allow a proposed new coal mine in Cumbria to go ahead, for example. It says it will double the cash commitment to insulating the UK’s draughty homes – making our homes more energy efficient is one of the toughest climate challenges the country faces.

Labour also says it will double the amount of onshore wind to 35GW by 2030. The Tories appear to remain lukewarm about land-based turbines despite loosening the planning rules a little last year. In fact, there is only one onshore wind project under construction in England at the moment.

Sign up for our Future Earth newsletter to get exclusive insight on the latest climate and environment news from the BBC's Climate Editor Justin Rowlatt, delivered to your inbox every week. Outside the UK? Sign up to our international newsletter here.

Most of the UK’s other parties don’t stray far on climate. The Lib Dems and SNP are a bit more ambitious on net zero - they say they’ll try and get there by 2045.

Ed Davey’s party says it will accelerate the deployment of wind and solar so that 90% of the country’s electricity is generated by renewables by 2030. The SNP has said it is worried that Labour’s plans to increase the windfall tax on oil and gas operations in the North Sea mean the loss of tens of thousands of jobs.

The Green Party says its aim is move towards net zero “as fast as is feasibly possible”. It says it “will commit to cutting greenhouse gas emissions with urgency, bolster our resilience to unavoidable climate impacts, and lead the global effort in transitioning away from fossil fuels”.

Meanwhile Plaid Cymru says the “climate and nature emergencies” are the biggest threat to mankind on a global scale. It says it aims to net-zero targets in Wales by 2035 but acknowledges that success will also depend on decisions made in Westminster.

The Reform Party is the only party with a radically different approach. It says it cares about the environment but proposes ditching the net-zero target altogether and getting rid of all renewable subsidies.

Maybe this broad consensus on climate shouldn’t be a surprise - after all, there are powerful forces limiting how far the major parties are willing to stray from the green centre ground.

New figures this week showed May 2024 was the warmest in recorded history globally, meaning the past 12 months have each been the hottest on record for the time of year. The UN chief Antonio Guterres responded with a warning that climate change was “pushing planetary boundaries to the brink”.

He said it was time for leaders to “decide which side they are on” because action this decade will be key to meeting climate targets.

More from InDepth

Russia's economy is growing, but can it last?

- Published6 June 2024

Nigel Farage’s return means turbulence for the Tories

- Published3 June 2024

Prince William's role is changing - what does he really want to do with it?

- Published2 June 2024

Politicians know lots of voters care deeply about the environment and neither party wants to alienate them. At the same time, with the country’s straitened economy, parties are reluctant to be seen to be making unfunded spending commitments on anything, including green initiatives.

What is clear, though, is that climate is one of the rare policy areas where the two main parties believe underscoring their differences of approach could deliver political benefits.

With Labour much more optimistic, stressing the opportunities investing in green industries could bring for the UK, the Tories take a more cautious approach, warning about the costs and risks to the country of moving too fast.

This growing distance between the Conservative and Labour parties is causing deep anxiety in environmental circles. Rhetoric does matter and they fear that what is essentially a matter of emphasis now could fracture into significant policy divisions in future.

Top image credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think - you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.

Get in touch

InDepth is the home for the best analysis from across BBC News. Tell us what you think.