The battle to save China's rare snub-nosed monkey

Watch: The BBC visits golden snub-nosed monkeys at Shennongjia National Park, China

- Published

Until the 1980s people roamed the mountains of Shennongjia in central China hunting monkeys for their meat and fur.

Poor farmers were still clearing vast areas of trees, and as their environment collapsed around them, so did the local population of golden snubbed-nosed monkeys, dropping below 500 in the wild.

This was the situation when new graduate Yang Jingyuan arrived in 1991, still in his early 20s.

"The monkeys' home was being destroyed by logging so their numbers were going down fast," he says. "Now it's being protected, and the monkey figures are really improving."

These days Professor Yang is the director of the Shennongjia National Park Scientific Research Institute and probably no one knows this species better than he does.

Professor Yang took the BBC into the forest to meet the rare monkeys

Prof Yang, 55, has spent his entire working life trying to understand and protect this endangered sub-species of snub-nosed monkeys, which exist only in these mountains in Hubei province, and he took us into the forest to meet them.

I asked if it was true that he now understood what many of their noises meant.

"Yes," he said. "Yeeee is telling others the area is safe. They can come over. Wu-ka means it's dangerous. Be careful."

And, sure enough, there he was making various noises as the monkeys came down out of the trees, holding our hands, touching us and checking out the humans.

The monkeys are found in the mountains of Shennongjia in central China

As we sat down on the ground to put them at ease, he said that these animals have a very complex social structure.

With baby monkeys jumping into my lap and crawling over us to see what was going on, Prof Yang explained how their groups break down.

One male head of a family group might have three to five wives, plus their children. Then families come together to form a larger band that could be more than a hundred.

Bachelor males form their own groups, which at times stand guard. Females have "affairs" behind their husband's backs, causing tension and fights break out not only when a male takes control of a family from an existing male head but when an entire "tribe" of monkeys battles with another for control of territory.

Six-year-old females know when it is time to leave their family and join another so as to prevent inbreeding and the animals – which live until around 24 years old – also know when it is time for them to die.

Near the end of their lives, we were told, they find a quiet place by themselves and go out alone. The rangers said the spots were so secluded that, over decades, they had never been able to find a monkey's body after this had happened.

That these unique animals can now exist in this way over an area of 400 square kilometres (155 square miles) is very different to how it was.

Finding the animals is difficult due to their speed

Though the national park was created in 1982, one 49-year-old ranger who grew up in the area, Fang Jixi, said that it took many more years for struggling farmers to stop destroying this environment.

"People were very poor in these mountains and hunger was a real concern. There was no concept of protecting wild animals," he said.

"Even after logging was banned there were still people illegally felling timber. If they didn't cut down trees, how would they have money? There were also people secretly hunting here to survive. It was only after a long period of building awareness that the consciousness of local farmers changed."

Part of this awareness was bringing these farmers on board to become protectors of the forest rather than wreckers of it.

"When the change occurred it was the scientists who told us you can actually come and work with us. You can have a job here to help the animals," Mr Fang said.

Now he is part of a team that patrols the hills, keeping an eye out for poachers and, most importantly, looking for where the monkeys are so that researchers can study how and where they sleep, forage and give birth.

Finding them can be difficult because the animals can cover an area through the treetops in minutes that a human would need an hour to walk.

What's more, these fascinating primates are not naturally so open to human interaction, especially given how dangerous such contact could have been in the past.

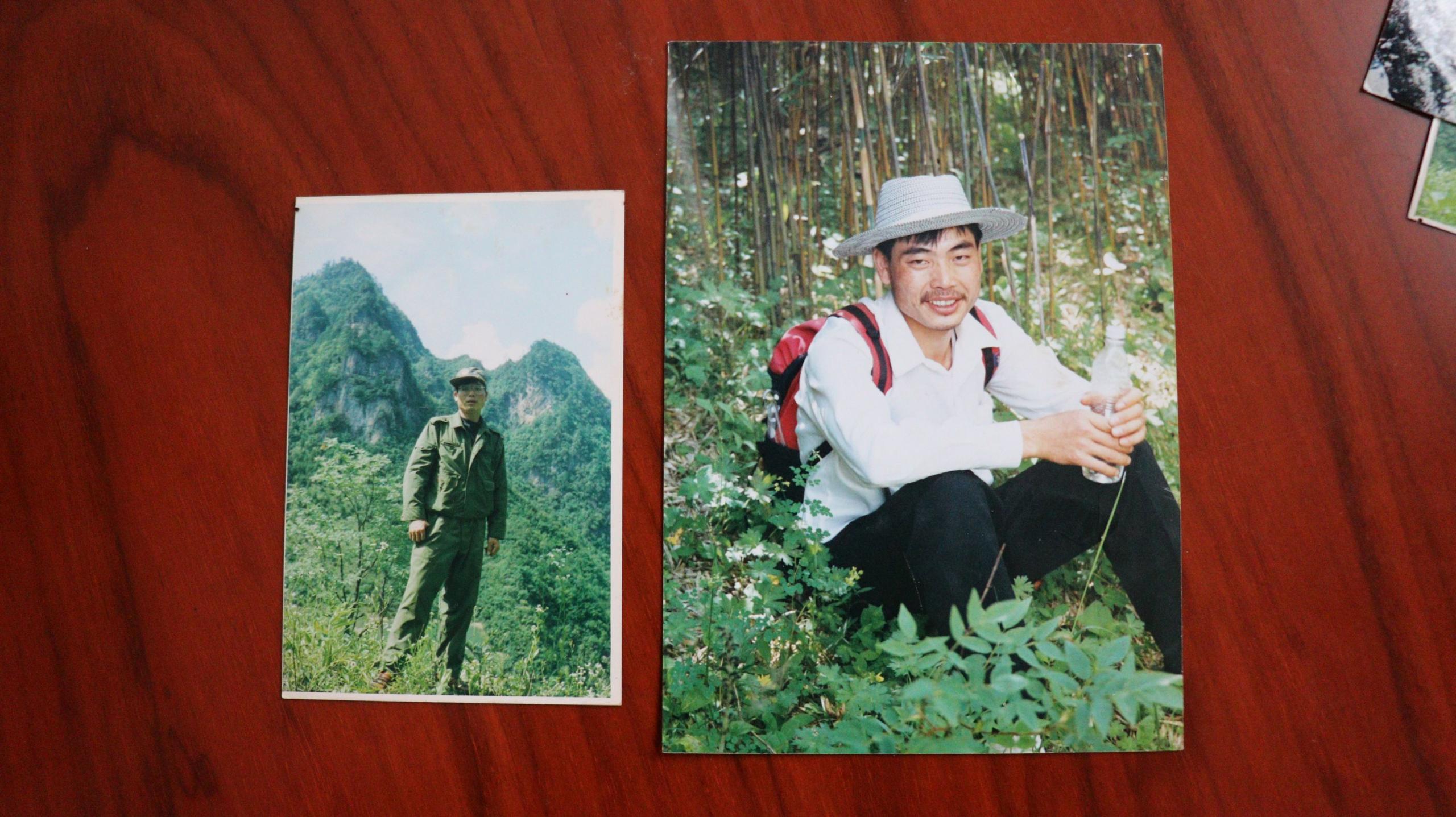

Prof Yang, pictured here in the 1990s, has spent his entire working life trying to protect the monkeys

It took a massive effort to turn this around.

The big push on preservation came in 2005 when Prof Yang and a small group of others formed a specialist study team.

In order to make contact with the specific group of monkeys we were sitting amongst in the forest, the team spent an entire year approaching them.

"They were very afraid of us at first. When they saw us from far away they all fled," said Prof Yang.

But – month by month – distances of 800 metres became 500 metres, then 200 metres until the animals allowed the team to be amongst them.

"I was so excited because finally they had become my friends. Every day we could be together and communicating," he said.

Old photos from the early days of Prof Yang's team show bare hills with tree cover of around 60% but when we put up a drone, from the top of a mountain, we could see that the reports of tree coverage currently at around 96% appear to be accurate.

The beauty of this place has naturally brought tourists in and millions of visitors have come through in recent years.

But, while the tourists can travel around many parts of the national park, dedicated monkey protection zones are off limits to all apart from approved staff members.

There are now roughly 1,600 monkeys and it is hoped that number will continue to rise

We were taken along a rugged mountain path in one of these zones.

We passed the camera and transmitter gear which had been set up to observe not only monkeys but black bears, boar and many other wild species in Shennongjia.

Then, from a breath-taking vantage point, shown a valley where farmers once lived but have now been moved to other locations to help protect the ecosystem.

We later spoke to one man who said he was happy to have left this remote, underprivileged existence. With the government support he got for the move, he and his family were running a guest house and much happier.

All this effort has been a tough road for Prof Yang's team, made even harder by the fact that the female golden, snub-nosed monkeys are so slow to reproduce, with only one child at a time, every two years. Also, not all their children survive.

Yet the 500 monkeys figure has now become more than 1,600 and they are hoping that this will pass 2,000 within 10 years.

"I'm very optimistic," said Prof Yang. "Their home is now very well protected. They have food and drink, no worries about life's necessities and, most of all, their numbers are growing."

Related topics

- Published20 August

- Published7 August