Bites on gladiator bones prove combat with lion

The skeleton of the young man was found during a 2004 dig in York

- Published

Bite marks found on the skeleton of a Roman gladiator are the first archaeological evidence of combat between a human and a lion, experts say.

The remains were discovered during a 2004 dig at Driffield Terrace, in York, a site now thought to be the world's only well-preserved Roman gladiator cemetery.

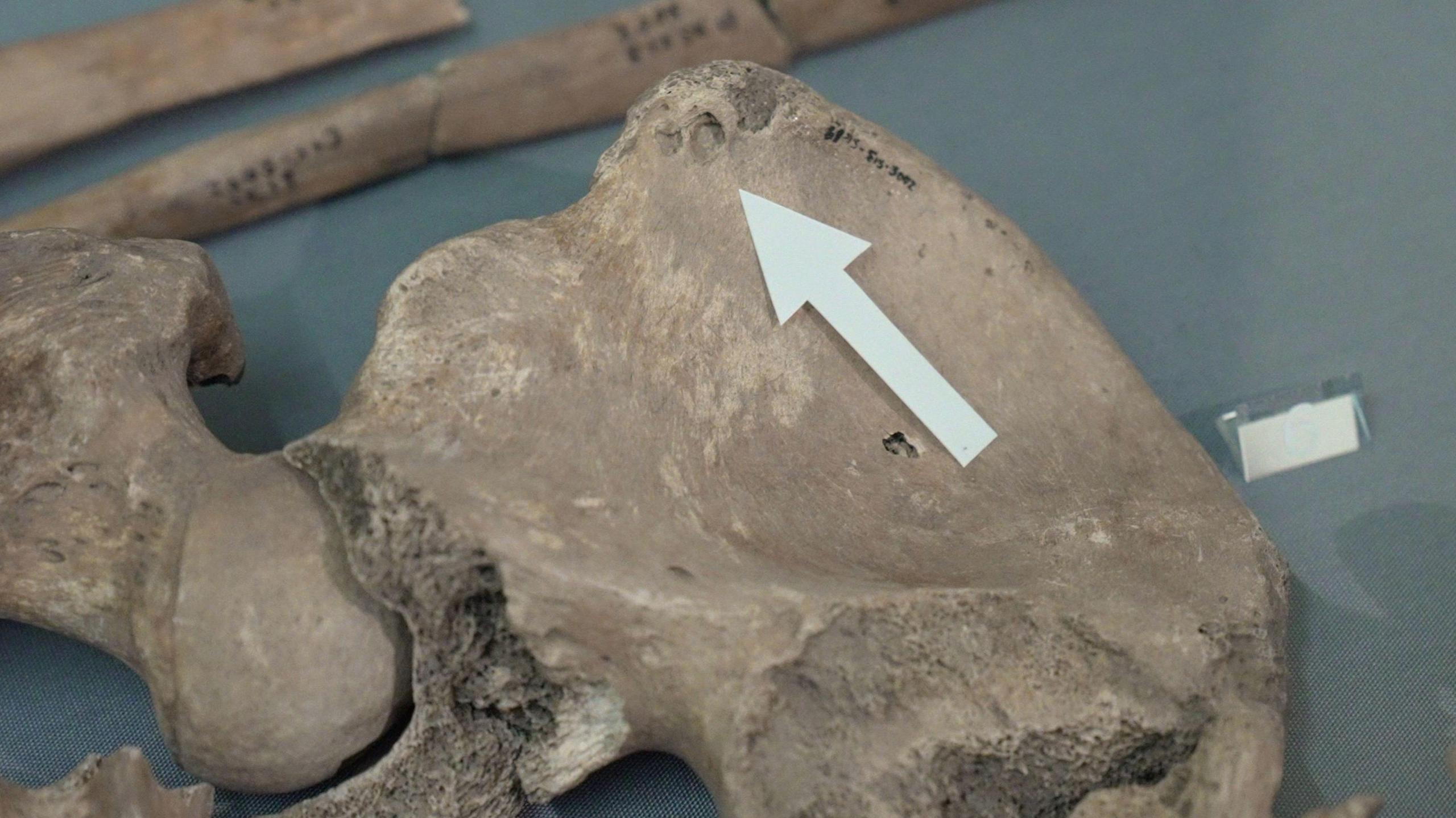

Forensic examination of the skeleton of one young man has revealed that holes and bite marks on his pelvis were most likely caused by a lion.

Prof Tim Thompson, the forensic expert who led the study, said this was the first "physical evidence" of gladiators fighting big cats.

"For years our understanding of Roman gladiatorial combat and animal spectacles has relied heavily on historical texts and artistic depictions," he said.

"This discovery provides the first direct, physical evidence that such events took place in this period, reshaping our perception of Roman entertainment culture in the region."

The bite wound was confirmed by comparing it to sample bites from a lion at a zoo

Experts used new forensic techniques to analyse the wounds, including 3D scans which showed the animal had grabbed the man by the pelvis.

Prof Thompson, from Maynooth University, in Ireland, said: "We could tell that the bites happened at around the time of death.

"So this wasn't an animal scavenging after the individual died - it was associated with his death."

As well as scanning the wound, scientists compared its size and shape to sample bites from large cats at London Zoo.

"The bite marks in this particular individual match those of a lion," Prof Thompson told BBC News.

The location of the bites gave researchers even more information about the circumstances of the gladiator's death.

The pelvis, Prof Thompson explained, "is not where lions normally attack, so we think this gladiator was fighting in some sort of spectacle and was incapacitated, and that the lion bit him and dragged him away by his hip."

Fictional depictions of gladiatorial combat with big cats have featured in films such as Gladiator starring Russell Crowe

The skeleton, a male aged between 26 and 35, had been buried in a grave with two others and overlaid with horse bones.

Previous analysis of the bones pointed to him being a Bestiarius - a gladiator that was sent into combat with beasts.

Malin Holst, a Senior Lecturer in Osteoarchaeology at the University of York, said in 30 years of analysing skeletons she had "never seen anything like these bite marks".

Additionally, she said the man's remains revealed the story of a "short and somewhat brutal life".

His bones were shaped by large, powerful muscles and there was evidence of injuries to his shoulder and spine, which were associated with hard physical work and combat.

Ms Holst, who is also managing director of York Osteoarchaeology, added: "This is a hugely exciting find because we can now start to build a better image of what these gladiators were like in life."

Malin Holst said the discovery was "hugely exciting"

The findings, which have been published in the Journal of Science and Medical Research PLoS One, also confirmed the "presence of large cats and potentially other exotic animals in arenas in cities such as York, and how they too had to defend themselves from the threat of death", she said.

Experts said the discovery added weight to the suggestion an amphitheatre, although not yet found, likely existed in Roman York and would have staged fighting gladiators as a form of entertainment.

The presence of distinguished Roman leaders in York would have meant they required a lavish lifestyle, experts said, so it was no surprise to see evidence of gladiatorial events, which served as a display of wealth.

David Jennings, CEO of York Archaeology, said: "We may never know what brought this man to the arena where we believe he may have been fighting for the entertainment of others, but it is remarkable that the first osteoarchaeological evidence for this kind of gladiatorial combat has been found so far from the Colosseum of Rome, which would have been the classical world's Wembley Stadium of combat."