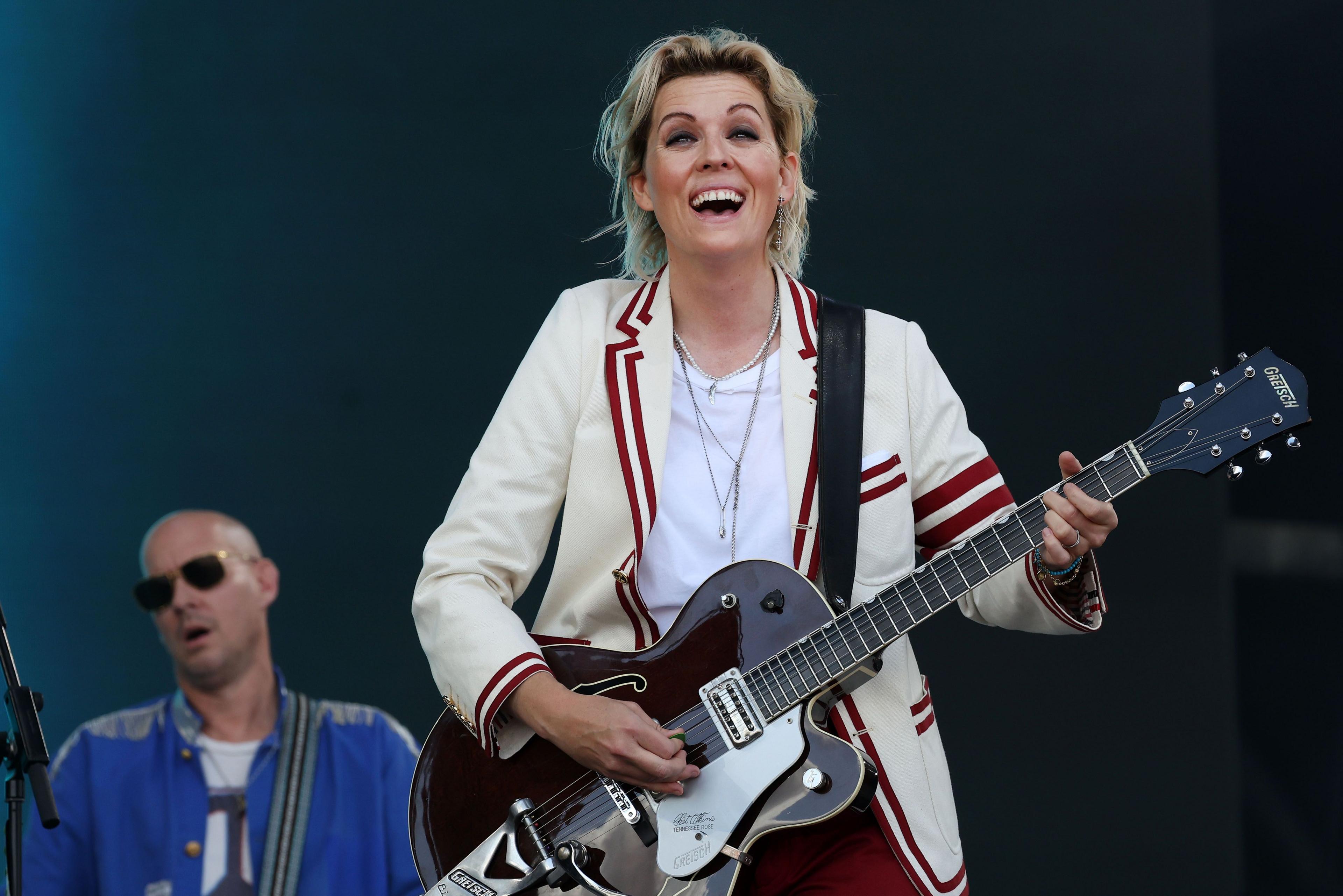

Brandi Carlile: 'Joni Mitchell is wild. She'll drink you under the table'

Carlile was a key part of Joni Mitchell's rehabilitation, sitting with her as she relearned her own lyrics after a brain haemorrhage

- Published

When Brandi Carlile was 12 years old, living in a mobile home in an isolated community 50 miles outside Seattle, she begged her parents for a piano.

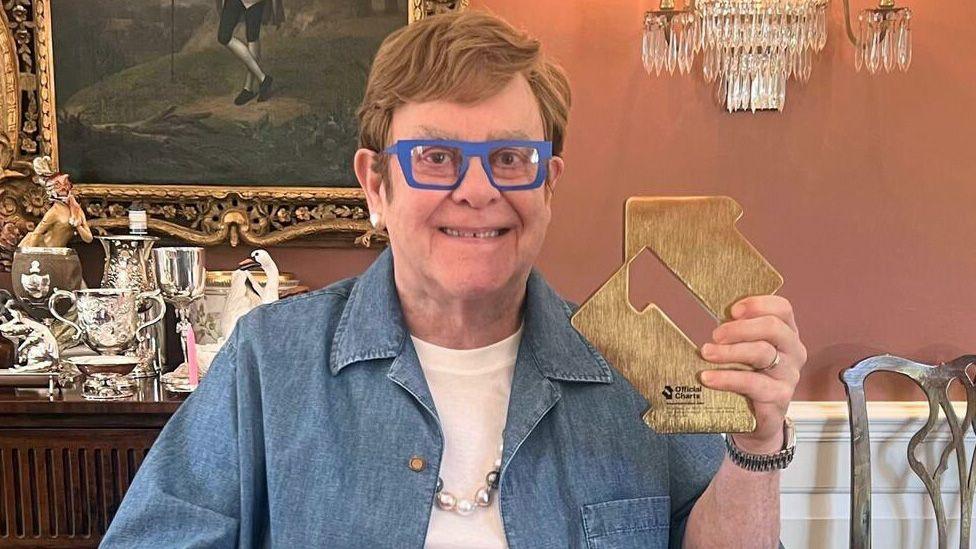

She'd fallen in love with her mum's Elton John albums and wanted to play along.

But when she broke her tiny Casio keyboard out of its Toys R Us box, she had to face an uncomfortable reality.

"I was just nowhere near talented enough," she laughs.

Instead, she put on Bruce Springsteen's Streets Of Philadelphia, dialled up the keyboard's "synth strings" setting, and pressed down two keys.

"You just hold them, all the way through the verse," she recalls. "Anyone can do it, but that's the foundation of my career."

Fast forward 32 years and Elton John is one of her best friends. In January, they released a collaborative album, Who Believes In Angels, that topped the UK charts (Carlile contributed significantly more than two notes).

The musician has also been responsible for Joni Mitchell's musical rehabilitation, coaxing the 81-year-old back onto the stage after a near-fatal brain haemorrhage.

And she's spent the last six years duetting with some of pop's biggest stars, from Miley Cyrus to Noah Kahan, while curating her annual Girls Just Wanna festival in Mexico.

All those opportunities stemmed from a single performance at the 2019 Grammys, where Carlile delivered a spine-tingling version of The Joke, an anthemic ballad for the persecuted.

"I'd played that song hundreds of times but I never could really hit that last note," she confesses now.

"But at the Grammys, I really wanted to get it right. So for days leading up to the show, I trained and I trained and I trained. And when I hit it, I could hardly finish the song. I wanted to jump up and down."

She wasn't the only one. Jaws were dropped. Eyes were popped. A star was born.

Before she'd even left the stage, Carlile's phone was blowing up with texts from people "so famous I couldn't fathom it".

"I suddenly had this river of opportunity flowing into my life, and I didn't know how long it was going to last, and so I said yes to everything," she recalls.

The star gave one of the stand-out performances at this year's Glastonbury festival, where she made her debut on the Pyramid Stage

Looking back, she reckons the eagerness to grasp those opportunities was a reaction to her childhood.

Growing up in rural America, Carlile knew she was gay, but had "never met" another gay person in her life.

Her sexuality changed her relationship with her mother.

"All the ways she thought she was going to relate to me, she couldn't," says Carlile.

"I didn't want to do make-up or learn to shave my legs or have long hair, and she was just like, 'What do I do with this child?'"

They eventually bonded over music - even forming a sort of informal tribute act to mother-daughter band The Judds.

But the sense of otherness remained, even after Carlile married and had two kids with British charity director Catherine Shepherd. So when opportunity came knocking, she felt obliged to chase it.

"I think it could be the gay thing, this kind of coyote thing, where it's like, 'Keep your eye on the prize. You're being included right now, you might not be included tomorrow. Accept everything, do everything, achieve, assimilate,'" she says.

Carlile formed a country supergroup with Maren Morris (left) and tempted Texan superstar Tanya Tucker (centre) out of retirement

Then, as suddenly as it arrived, the instinct vanished.

Last October, she flew straight from a show with Joni Mitchell to a recording session with Aaron Dessner - co-founder of rock group The National, and a key collaborator for Taylor Swift.

By the time she landed in New York, she was hungover and overwhelmed with emotion. Instinctively, she knew the comeback concerts she'd masterminded with Joni had run their course.

"I couldn't bear the thought of not sitting next to her and listening to her sing Both Sides Now again," she says. "I'd had the best damn seat in the house."

Dessner showed Carlile a few pieces he'd been working on, then left her to work in his barn. Exhausted, she went upstairs, climbed into bed, and wrote a poem that captured her mood.

"Returning to myself is such a lonely thing to do / But it's the only thing to do."

After six years of chasing opportunities, it was time to turn inwards.

"I knew I was at the end of something," she says, "and that, yes, the phone might stop ringing, but I don't want to miss out on my kids' childhood."

"When I look back on my life - my sense of serial monogamy, being raised in an addicted household, I don't think I ever have come into myself in some ways," says Carlile

The poem became the title track and north star for her new album, which wrestles with the passage of time, and the delicacy of human connection.

When Dessner started playing atmospheric synth chords in the studio, it unlocked the memory of those first musical experiments on her Casio keyboard.

"I felt 13 or 14 again, and it made me write things differently," she says. "I had this huge lump in my throat the whole time. I was embarrassed to sing the songs in front of everybody because I thought I would cry - and I did."

Listeners might need a box of tissues, too.

When Carlile played You Without Me at Glastonbury this summer, there were more than a few misty eyes, as people digested the story of a parent coming to terms with their child's independence.

"I've started to see those moments, and it's soul crushing," says the singer, whose eldest daughter, Evangeline, is 11. "But at the same time you're overwhelmed with pride."

Same-sex marriage threat

Her daughters inspired one of the record's angrier songs, too. Church And State rails against the increasing influence of conservative religious ideology on US politics.

Recorded live on election night 2024, it addresses Carlile's fear that the Supreme Court could overturn Obergefell v Hodges, which recognised same-sex marriage in 2015.

It was prompted by a dinner conversation, where Evangeline suggested the family could just get on Carlile's boat and "bebop up to Canada" if gay marriage was outlawed.

"I don't want to go to Canada," protested their youngest, Elijah.

"And Evangeline just snapped and said, 'Elijah, it's better than not having a mommy or a mama'.

"I felt so ashamed for not explaining it better. They assumed that if it ever happened, they'd be orphans.

"And then I felt so angry that something so archaic and antiquated could even be a possibility in the country I live in, let alone legitimately on the horizon."

Carlile helped to orchestrate the "Joni Jam" concert series, where Mitchell would hold court over a rotating cast of musicians, performing some of her biggest songs and deepest cuts

The album's other guiding light is Mitchell, whose strict quality control is "the reason I write a lot fewer songs," Carlile says.

She pays an affectionate but cheeky tribute to the singer on a song simply called Joni.

"She doesn't suffer fools, she won't make cups of tea, and she won't bandage bruised egos," sings Carlile over a delicately plucked guitar.

"She is a wild woman," laughs the star. "She's 83 and she will drink you under the table.

"She loves Cadillac margaritas and plain Black Jack. And she is unpredictable, untameable, unknowable sometimes, and it's amazing."

Presumably it was nerve-wracking to play Mitchell the song?

"Oh, I was quaking," she laughs. "She was sitting at her desk in her bedroom, putting butterfly clips in her hair, as Joni Mitchell does, and just listening to the song with this furrowed brow, not reacting whatsoever.

"But this big smile spread across her face after the last chorus. Then she made me wait a good minute before she nodded at me like, 'This is great.'"

One lyric, however, created a little friction.

"When I tell you I love you, and you tell me 'OK'... That's love in your way."

"When she heard that she called me an asshole!" Carlile laughs, "because she knew exactly what I meant - and you're not supposed to get Joni Mitchell. She doesn't want to be understood."

As you might expect, Carlile is full of similarly starry anecdotes.

She recalls seeing Paul McCartney at the side of the stage during her Glastonbury set ("that was a top five moment"); and spills the beans on Dolly Parton's tattoos ("I haven't seen them, but I know people who have. She can be really rugged and curse.")

So what would that lonely child, who warmed her hands around a wooden stove and struggled to play Elton John songs, think about her elevation to the highest echelons of music?

"I have a lot of affection for that girl now, in ways that I didn't at the time," she reflects.

"She would love to know that it happened and that she made it. Because I've made it beyond where I hoped, and I'm not sure what to do with that."

If Returning To Myself is the first draft of her answer, it suggests the possibilities are limitless.

With a new confidence and a new direction, Carlile is breaking into uncharted territory: Herself.

Related topics

- Published11 April

- Published10 February 2015