The French would dearly love to know who is the real Jordan Bardella.

The question was interesting when Mr Bardella was merely president of the country’s biggest party, the far-right National Rally (RN).

Now that he is being openly spoken of as the country’s next prime minister, it has become a matter of urgency.

In two weeks the country goes to the polls in a snap election called by President Emmanuel Macron following his humiliation by the RN at the European elections last Sunday.

If the RN has pulled off another big win after the second round of voting on July 7, then Macron will have no choice but to offer it a chance to govern. And if that happens, Mr Bardella – who shares the party leadership with Marine Le Pen – is expected to be named as prime minister.

The French all know the basics about Mr Bardella, and his lightning rise from jobless school-leaver in the northern Paris suburbs to Le Pen protégé and president of the party.

They know that he is ridiculously young, just 28, but that this seems to matter less nowadays, when experience no longer counts for much. The current president is just 46, and the prime minister 35.

They know he is perpetually neat, that he speaks well, is ultra-presentable.

But what he thinks, where he stands ideologically, what kind of person he is – these are unknowns. The French have the distinct feeling that the man they see is a package. Nicely-wrapped, but the contents are a mystery.

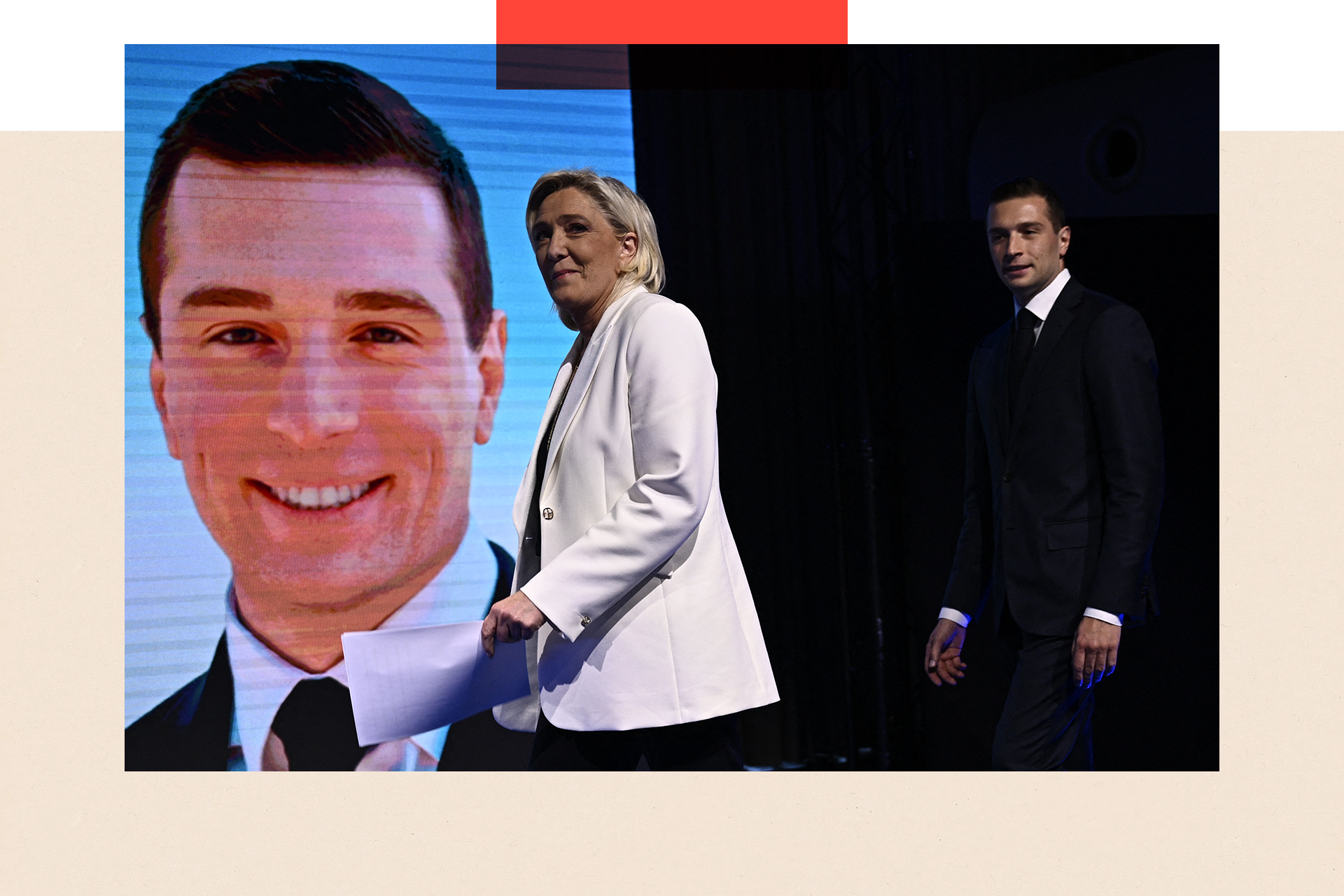

Jordan Bardella's potential was quickly spotted by Marine Le Pen

The official version of Mr Bardella – the one on the label – is a young man who grew up in a deprived estate in Seine-Saint-Denis and after living with the scourge of drugs, poverty, lawlessness and uncontrolled immigration came to believe that only the hard-right had the answer.

This is “le story-telling”, a French borrowing from the world of marketing.

As he himself has said: “I am in politics because of everything I lived through there. To stop that becoming the norm for the whole of France. Because what happens there is not normal.”

The truth is more nuanced. Mr Bardella was indeed brought up by his single mother, Luisa, in the Cité Gabriel-Péri in the town of Saint-Denis, so his experience is real enough. Both his parents are of Italian origin, and his father had an Algerian grandmother.

But Mr Bardella’s father, Olivier, who moved out when Jordan was very young, ran a drinks distribution business, and was relatively well off. He lived in the commuter town of Montmorency. And Mr Bardella did not go to the nearest state school, but to a semi-private Catholic establishment popular with the middle-classes.

“The young Bardella had a foot on either side of the tracks,” said Pierre-Stéphane Fort, the author of a critical biography of the RN president.

For a recent profile in Le Monde newspaper, the authors went back to Saint-Denis to find friends and acquaintances of the young Mr Bardella.

They found he had left little trace. Friends – of mixed racial backgrounds -- remembered that he was a fan of video games, and set up a YouTube channel to discuss the latest releases. They recalled that he had given literacy classes to immigrants after hours at his lycée when he was 16. But they did not remember any particular interest in far-right politics.

“My theory is that he looked around the political world and spotted the place where there was the best chance of climbing the ladder,” Chantal Chatelain, a teacher at his lycée, told Le Monde.

Mr Bardella joined the party at 17, and his rise was meteoric. It happened because he became part of Ms Le Pen’s outer circle.

Much at the top of the RN operates around personal relationships and clan loyalties, as it did when Ms Le Pen's father, Jean-Marie, was at the helm of the party that was then known as the Front National (FN). Mr Bardella became the boyfriend of the daughter of an old FN hand, Frederick Chatillon.

Jordan Bardella joined the Front National age 17

Within days of being introduced to Le Pen in 2017, she had named him the party spokesman. In 2019 she asked him to head the party’s candidate list at the European elections, which the RN won. He became an MEP. Then in 2022, she made him party president.

According to Pascal Humeau, a media trainer who worked with Mr Bardella for four years, Ms Le Pen spotted straightaway how the young man – with his perfect tale of banlieue hardship – would be of service to the party. She called him her “lion cub.”

But Mr Humeau is far from complimentary about Mr Bardella himself. The two parted ways after a row over money, so his testimony needs to be treated with caution. But today he describes the RN leader as a product of pure PR.

“He was an empty shell. In terms of content there wasn’t much there,” Mr Humeau said. “He didn’t read much. He wasn’t curious. He just absorbed the elements of language given him by Marine.”

Mr Humeau said he worked for months on getting Mr Bardella to shed his stiff bearing, and to smile more naturally. “I had to humanise the cyborg. My job was to get people who would otherwise hate him to say, ‘huh! for a fascist he’s nice!’”

The biographer Pierre-Stephane Fort is another critic of Mr Bardella who says there is little substance behind the personable image.

“He is a chameleon. He adapts perfectly to the environment around him,” he said. “And he is a chronic opportunist. There is no ideology there. He’s pure strategy. He senses where the wind is blowing, and gets in there early.”

Indeed, identifying Mr Bardella with any of the RN’s different courants or political clans is impossible. At different times he has been with the “social” wing, with its focus on the poor and building social housing, and the “identity” wing with its focus on race and preserving French culture. But mainly he goes where Ms Le Pen goes.

Like her, and the party as a whole, he has a general standpoint built around a tough response to crime and immigration, and has spoken of France being “submerged by migrants”. But on specifics, the answers are left deliberately hazy.

Emmanuel Macron shocked France when he called an election

On the stump with Mr Bardella, there is no denying his popularity. Young women think he is “gorgeous”, and he has a smile and a selfie for everyone. But watch for a while, and you see the smile routine coming round again rather too automatically.

And listen for a while, and you hear the same tropes and formulae coming round again too.

At a recent TV debate with the prime minister Gabriel Attal, Mr Bardella held his own, but it was obvious who was the smarter. Luckily for Mr Bardella, Mr Attal blew his advantage by adopting a constant smirk – exactly the kind of condescension that the RN feeds on.

For Ms Le Pen, the lion cub has been a huge asset, and has allowed her to broaden the party’s appeal far beyond its traditional social categories. With his TikTok habit, Mr Bardella obviously connects with the young. He regularly posts short videos of himself (which have been packaged up by a media company) to his 1.3 million followers.

He also has a good rating among graduates, pensioners and city-dwellers – segments that have proved resistant to the RN in the past.

But the question has still not been answered. Is his appeal merely the result of brilliant communication, or is this a man with the right stuff to run the country?

He is 28, never went to university, and has no experience of government. He has never held a job outside the RN, apart from a month one summer at his father’s company. Until recently, this would have made it inconceivable that he be named prime minister of France.

But do the old rules still apply?

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think - you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.

Get in touch

InDepth is the home for the best analysis from across BBC News. Tell us what you think.