Labour’s first week: Eight key plans, and the challenges ahead

- Published

It’s been a busy first week for Labour, with a raft of announcements including plans to tackle prison overcrowding, get people back into work and build 1.5 million new homes.

But what are the hurdles that lie ahead?

Finding the cash for wind power

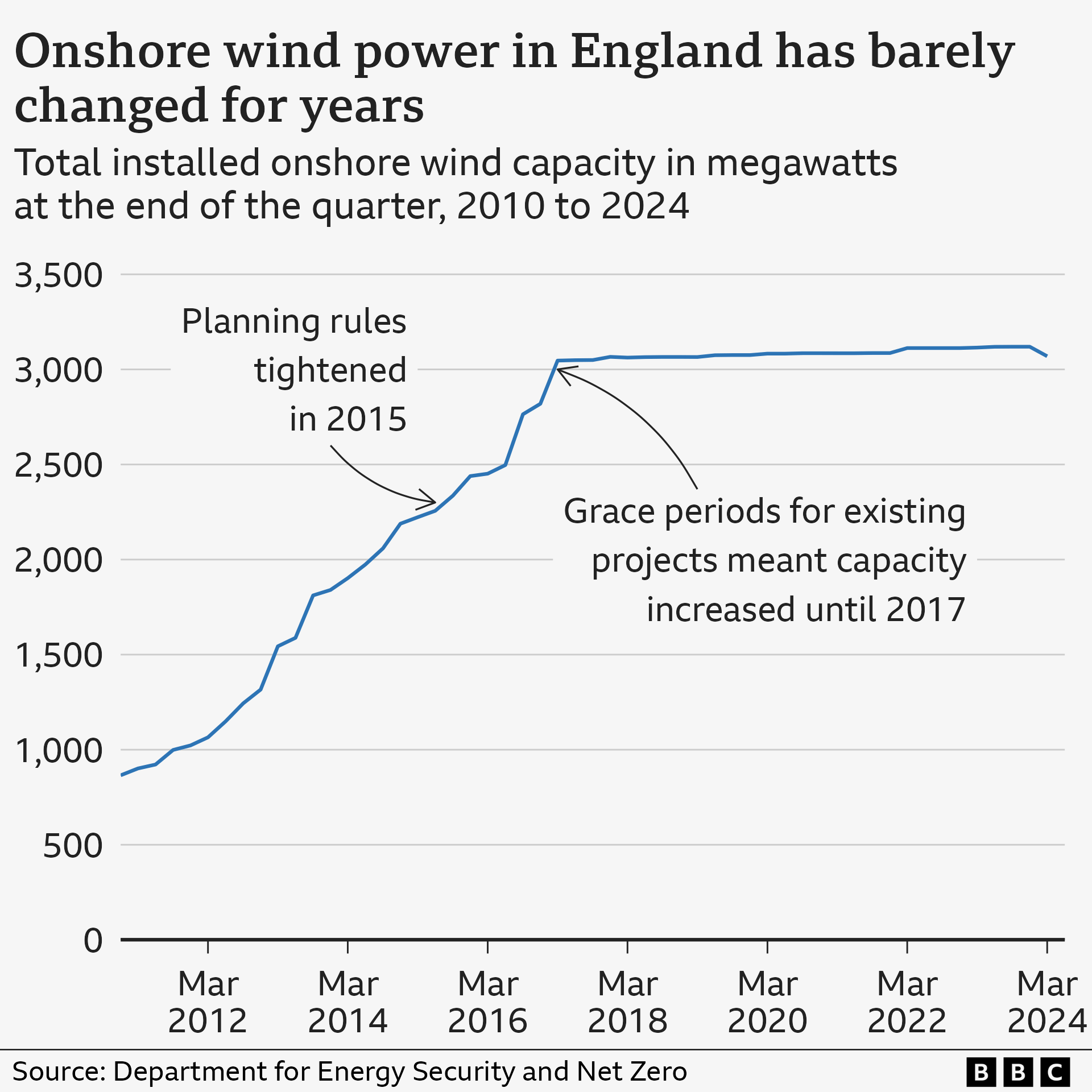

Wind is a key engine of change for Labour, who believe it will help the UK economy grow. The new government has promised big steps - doubling onshore and quadrupling offshore turbines by 2030. By removing the ban on onshore wind in England just a few days into power, Labour wants to show this is a key priority.

The announcement was welcomed by the industry, with reports of big developers such as Germany’s RWE and France’s EDF wanting to move ahead with new onshore projects. Overcoming local objections about the visual impact of land-based turbines will be vital. Community energy activists say public attitudes are changing, and the potential to offer discounts to local consumers is softening opposition.

Offshore, Labour's plans face huge hurdles, with global shortages of materials and skills. The big change that’s needed will be making offshore investments more financially attractive.

Last year, there were no takers at a government auction for new contracts to develop offshore wind, with firms saying the price set was far too low. While Labour starts with great goodwill, it will ultimately be cash that decides whether their wind promises are met.

Will new homes help first time buyers?

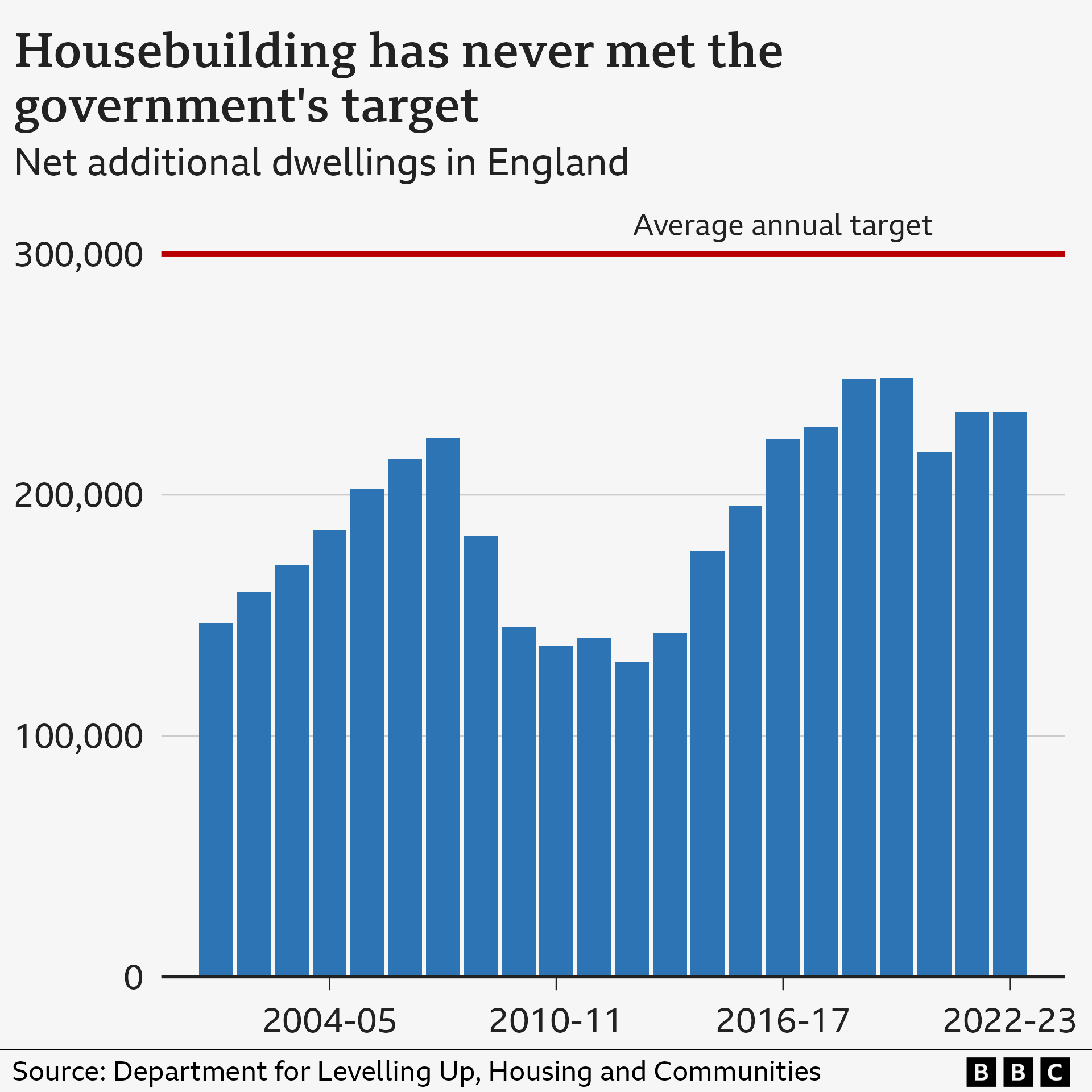

In her first speech as chancellor, Rachel Reeves vowed to "get Britain building again", to boost economic growth. Compulsory housebuilding targets ditched by the previous Conservative government are back, and Ms Reeves said the government was willing to take an “interventionist approach” to achieve them.

As stated in Labour’s manifesto, ministers want 1.5 million homes built in England in five years. That’s a daily average of 822 homes, or roughly a new housing estate, every day. But a target is one thing, and delivering a level of housebuilding not seen since the 1960s is another.

The plans will rely significantly on private housebuilders. While they may have the capacity, the market conditions and commercial justification will have to suit them. Questions have already been raised about whether a sufficiently skilled workforce is available. And strap yourselves in for some battles at local level when council planning committees face potentially stiff opposition from residents.

Perhaps the biggest questions of all for young voters is whether this will all make a first home cheaper or easier to buy.

Making a clear plan to fix the NHS

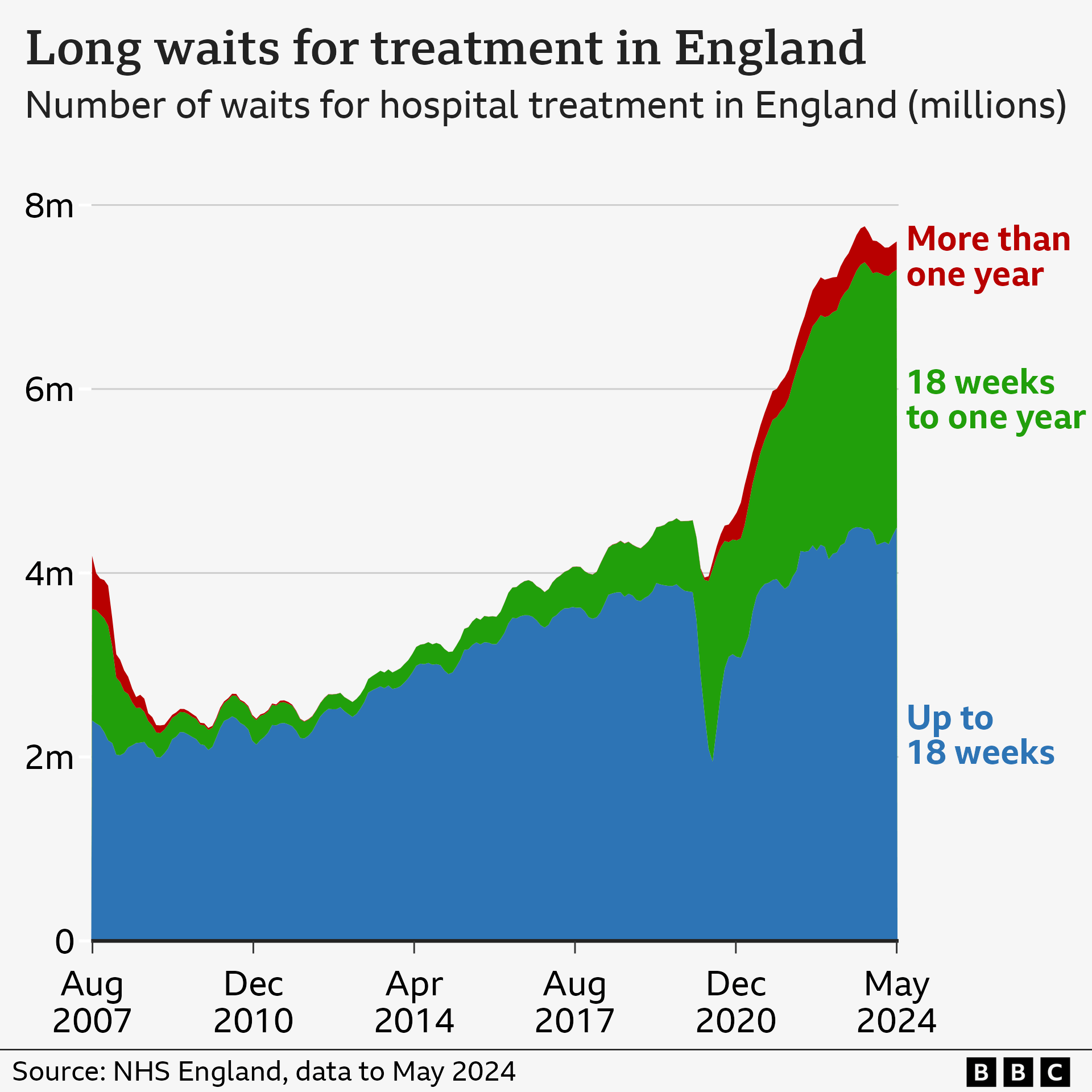

Health Secretary Wes Streeting made headlines within hours of starting, declaring the NHS "broken" because of the long waits patients face.

Tackling the backlog for hospital treatment was a key priority in Labour’s manifesto. It promised an extra 40,000 appointments and operations a week in England, by getting NHS staff to work weekends and using the private sector more.

But that will not be easy. Despite more money and staff, the NHS has struggled to increase the number of patients its sees in recent years.

Mr Streeting has not set out much more detail, except for announcing an investigation into performance led by NHS surgeon and independent peer Lord Ara Darzi. That will report back by September.

If the new government is to achieve its aim of getting waiting times back on track, a clear plan and signs of progress will need to follow quickly.

Questions over defence spending remain

Sir Keir Starmer was lucky to have a Nato summit in his first week. It gave him an early chance to meet important allies, including a one-on-one meeting with US President Joe Biden. The prime minister also met key European leaders, promising a reset in Britain’s relations with the EU. The summit allowed him to demonstrate his government’s support for Ukraine, confirming the UK would continue to provide £3bn in military aid each year.

Sir Keir announced a strategic defence review would begin next week and said his commitment to spending 2.5% of national income on defence was “iron clad”. But he faced criticism for refusing to say when or how that target would be met.

The challenge for the prime minister and other Nato allies will be how to remain united in their support for Ukraine, as not all are equally resolute. They must also plan for the possibility of a Trump presidency that could see a significant reduction in US military backing for Kyiv.

Labour manifesto: What they plan to do in government

- Published5 July 2024

Labour manifesto 2024: 12 key policies analysed

- Published13 June 2024

Who's in Keir Starmer's new cabinet?

- Published16 September

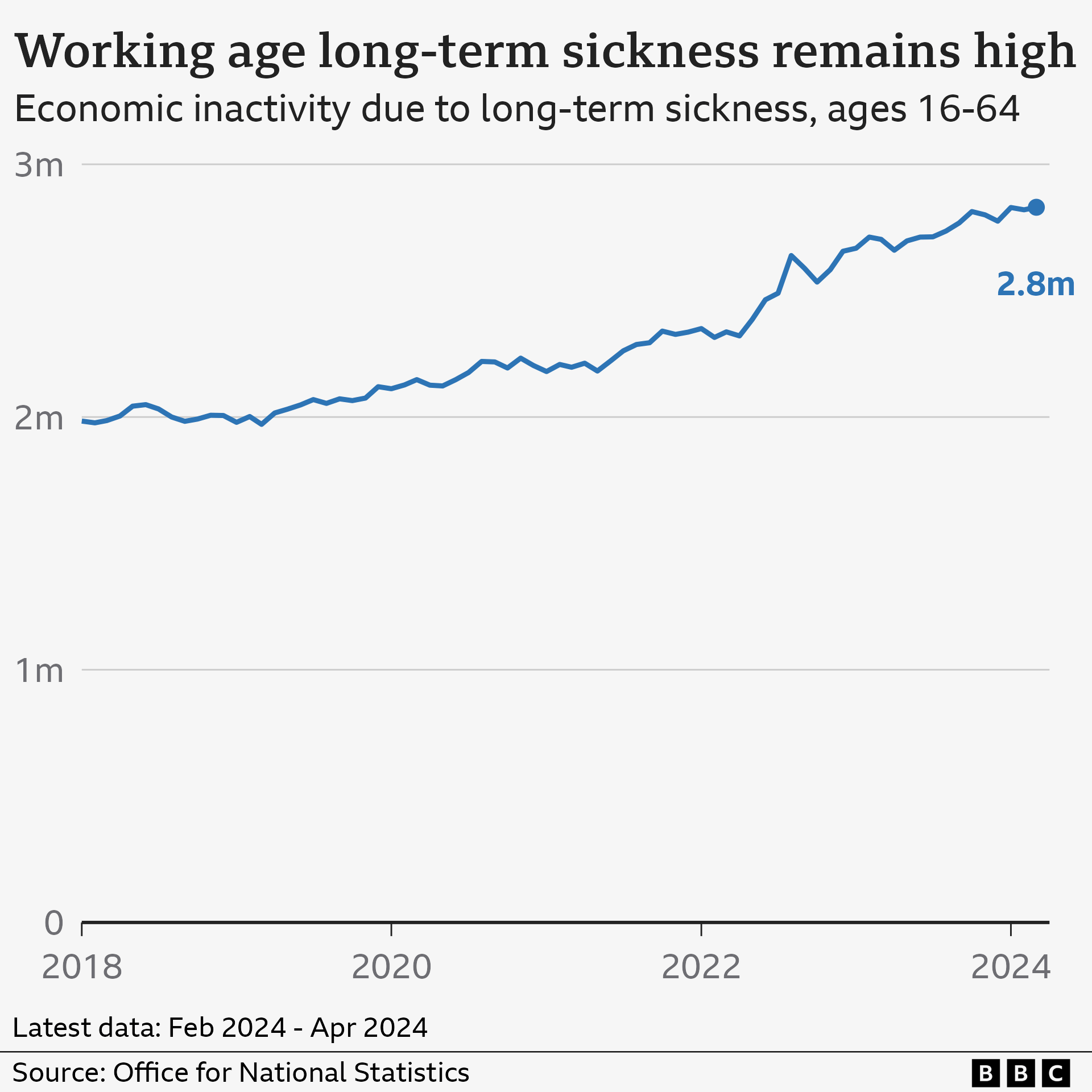

Helping people back into work

The number of people who are economically inactive due to ill health has risen by 700,000 since the pandemic, to 2.8 million. The government’s big idea to tackle rising levels of worklessness is to create a new national jobs and career service. It would be based in job centres, but with local areas able to tailor the scheme depending on their own employment needs.

Work and Pensions Secretary Liz Kendall has praised initiatives in Manchester, where the Greater Manchester Combined Authority has invested money in programmes such as Working Well. This helps people with health conditions and disabilities get “the right job, at the right time.”

The biggest challenge will be changing perceptions of job centres. For many, they aren’t places to find work and instead mean fearful encounters with officials focussed on ensuring claimants comply with benefit rules. “Take a job - any job - or you’ll lose your benefits,” has been the message the unemployed have often left with. If that image doesn’t change, the government’s plan could well be stymied.

How to deal with asylum seeker backlog?

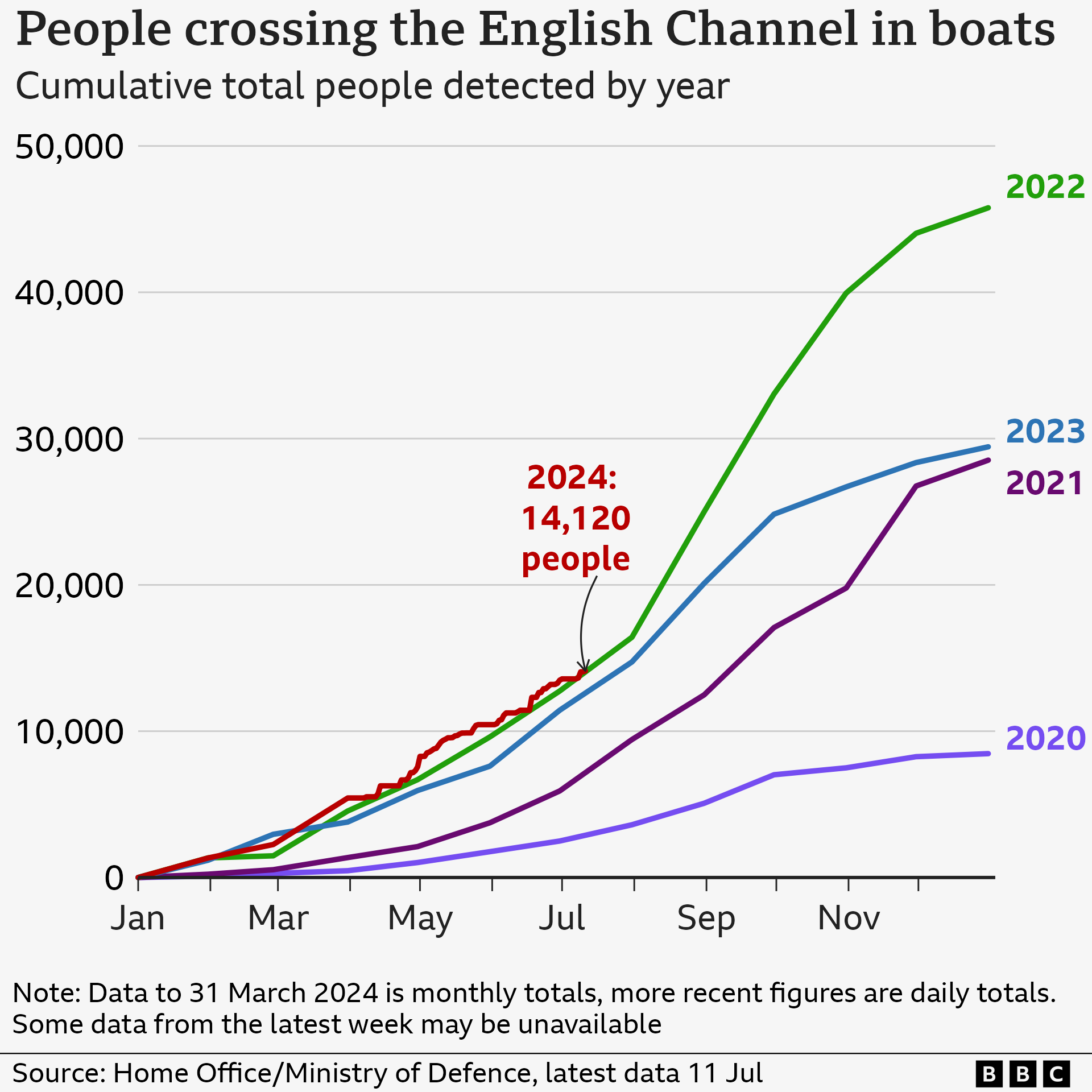

Labour’s manifesto promised to scrap plans to send asylum seekers to Rwanda and set up a new Border Security Command (BSC) to tackle the people smuggling gangs moving tens of thousands of people across the English Channel in inflatable boats.

After taking up office, the prime minister swiftly confirmed the end of the Rwanda plan, and Home Secretary Yvette Cooper said there would be “rapid recruitment of an exceptional leader" for the BSC.

Labour said the new BSC would be partly funded by diverting £75m from the Rwanda policy, set up by the Conservatives in 2022. By the end of 2023, £240m had been paid to Rwanda. However, Rwanda has said it will not be giving any money back.

The one diplomatic mistake of Labour’s first week was its failure to inform the Rwandan government before announcing the end of the joint migration policy, which angered Kigali.

Labour also promised to end the "perma-backlog" of asylum seekers whose claims are not being processed because of the Illegal Migration Act, which says people who arrive illegally cannot claim asylum. However, the new government has not said how it plans to deal with the estimated 100,000 people caught in this legal limbo.

Tough talk over water bills

Labour's so called "crackdown" on water companies includes ring-fencing money for infrastructure investment so it doesn't leak out into bonuses, dividends or pay increases. New customer panels will be able to summon water executives to answer for their performance. Compensation payments to households and businesses whose basic services are not up to standard will more than double.

But water firms have said a proposed average 21% hike in bills in England and Wales by 2030 won't be enough to address problems including sewage leaks. It is a third less than the amount they requested. They are now in a stand-off with regulator Ofwat over how much prices can rise.

What the government wants to avoid is having to nationalise a company like Thames Water, which is drowning in £18bn of debt and says it only has enough cash to last 11 months. Environment Secretary Steve Reed has warned nationalising water companies is not something it wants to do. He says it would “cost money we do not have” and slow down the process of reducing pollution levels.

Labour is talking tough, but solving the stand-off between the firms and the regulator is one of the big issues it now has to resolve.

Prison release plans not without risk

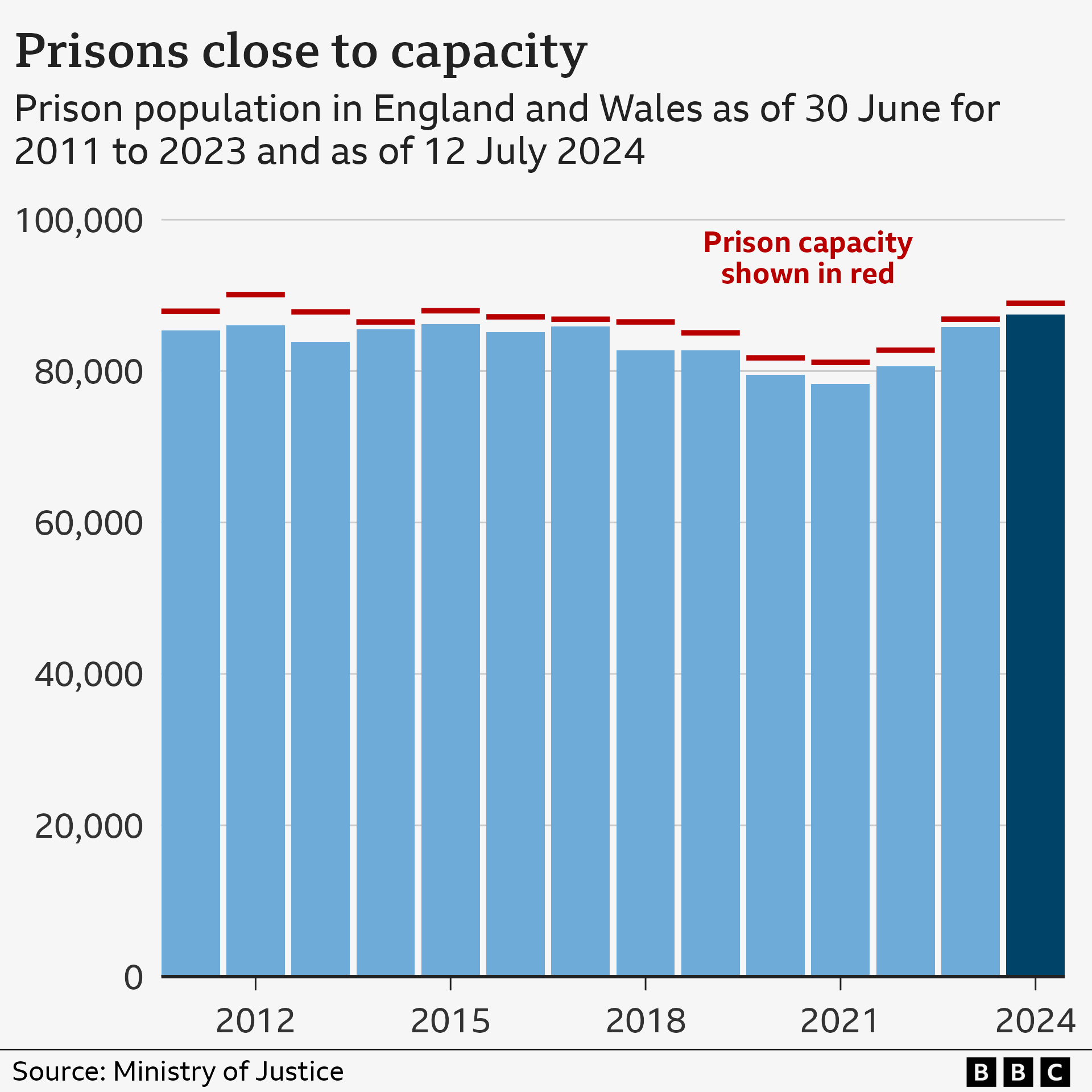

Jails in England and Wales are on the cusp of reaching full capacity and prison staff say they’re under immense pressure to find spaces that don’t necessarily exist.

The Labour government wants to continue building new prison places announced by the Conservatives, but has not said when they will be completed.

The government argues that it has had no choice but to announce it will release some prisoners early to free up urgently needed space.

But releasing inmates comes with risk. The new government could be seen as soft on crime among those who support longer and tougher sentences. And what if one of those let out early goes on to commit another more serious offence?

Ministers are going to have to be very careful who they release, with sources saying we could be looking at thousands let out in the autumn. Serious offenders such as rapists and murderers are exempt from the plans.