Child hospital care dates from 18th Century - study

Between 1744 to 1801, some 4,163 patients aged 13 and under were treated at Northampton Infirmary and of these 56% were male and 43.3% female, records reveal

- Published

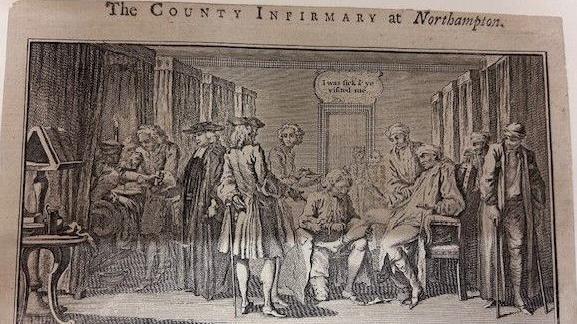

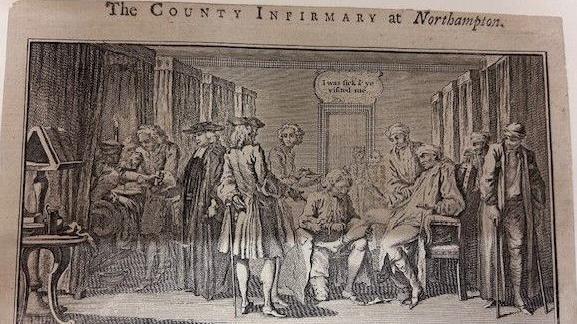

Researchers have discovered children received hospital care as far back as the mid-18th Century.

The findings are based on Northampton General Hospital's archive, which revealed up to 12% of its annual patients were children after it was founded in 1744.

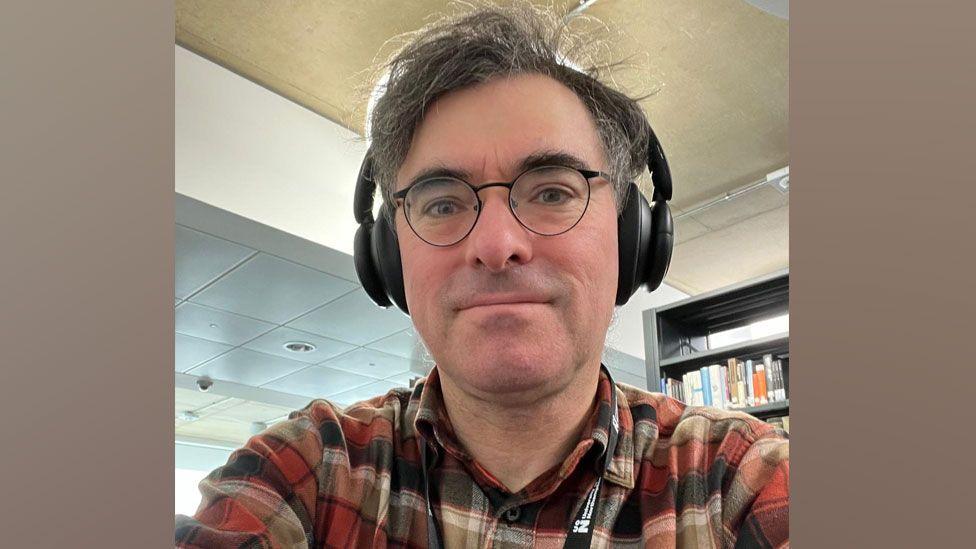

Prof Andrew Williams said this overturned the belief "children were just not admitted to hospitals at all" until specialist institutions were created in the 19th Century.

In fact, the very first inpatient admitted to what was then called Northampton Infirmary was Thomasine Grace, 13, from Stoke Bruerne, near Towcester, he said.

"She'd had scald head [ringworm] since her infancy — severe ringworm for more than a decade," said Prof Williams, a former paediatric consultant at Northampton General.

"The way you treat that is ample good quality food and because she was poor, she was malnourished, because her family couldn't have afforded the care she needed."

The hospital took children from all over the county before Kettering General Hospital opened in 1897

The project was a collaboration between the Northampton General Hospital archive, the University of Northampton and the University of Toronto Mississauga in Canada, which financially supported the students involved.

They examined the infirmary's admission register, which listed patients' full names, parishes, illnesses, who was recommending them for treatment, dates of admission and discharge and whether patients were cured.

Prof Williams, who is Northampton University's visiting professor of child health and medical history, described it as "a pretty rare document".

"We have demonstrated that more than 4,000 named children, aged 13 years and under, were treated for described conditions between 1744 and 1801," he said.

"Our research suggests that several thousands of children were annually seen in voluntary hospitals in the 18th Century regardless of regulations that in many cases banned them."

The hospital's archive volunteer Fred O'Dell said the children came from all over Northamptonshire.

Prof Williams said that after 1804 patient ages were not recorded but he thought it probable the infirmary treated more than 10,000 children up to 1852

Prof Williams said when he was training as a doctor in the 1980s and 1990s, most historians believed paediatric hospital care did not start until the creation of specialist institutions such as The Hospital for Sick Children at Great Ormond Street in London in 1852.

This was because 18th Century voluntary hospitals were usually paid for by contributions from local employers whose primary aim was to get people fit and back to work.

It was thought children were not accepted as patients so the limited resources of early hospitals could focus on that goal.

'Evolution in paediatrics'

Prof Williams said Thomasine was treated as a hospital inpatient for more than 100 days.

She went on to get married in Shoreditch in London, in March 1762.

"What is really unusual about her marriage certificate is she is able to write her name — she's not putting her 'mark'," he said.

"Almost certainly she was taught to read and write while she was an inpatient."

He suspects just as part of the infirmary's remit was to get its adult patients back to work, by teaching children to read and write it would increase their employment opportunities.

University of Northampton professor of molecular medicine, Karen Anthony, said the research "illuminated previously unknown chapters in the development of child and adolescent healthcare in the England, research that places Northamptonshire near the centre of this vital evolution in paediatrics".

Little lives—reading between the lines: insights from the Northampton Infirmary Eighteenth Century Child Admission Database has been published by Medical History, external.

Get in touch

Do you have a story suggestion for Northamptonshire?

Follow Northamptonshire news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external.

Related topics

More stories of interest

- Published24 February

- Published22 December 2023