'I can't afford to save both twins': Sudan's war left one mother with an impossible choice

Touma's life and family have been devastated by Sudan's civil war

- Published

Warning: This piece contains details that some readers may find distressing

Touma hasn't eaten in days. She sits silently, her eyes glassy as she stares aimlessly across the hospital ward.

In her arms, motionless and severely malnourished, lies her three-year-old daughter, Masajed.

Touma seems numb to the cries of the other young children around her. "I wish she would cry," the 25-year-old mother tells us , looking at her daughter. "She hasn't cried in days."

Bashaer Hospital is one of the last functioning hospitals in Sudan's capital, Khartoum, devastated by the civil war which has been raging since April 2023. Many have travelled hours to get here for specialist care.

The malnutrition ward is filled with children who are too weak to fight disease, their mothers by their bedside, helpless.

Cries here can't be soothed and each one cuts deep.

Touma and her family were forced to flee after fighting between the Sudanese army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) reached their home about 200km (125 miles) south-west of Khartoum.

"[The RSF] took everything we owned - our money and our livestock - straight out of our hands," she says. "We escaped with only our lives."

With no money or food, Touma's children began to suffer.

She looks stunned as she recounts their old life. "In the past, our house was full of goodness. We had livestock, milk and dates. But now we have nothing."

Sudan is currently experiencing one of the world's worst humanitarian emergencies.

According to the UN, three million children under the age of five are acutely malnourished. The hospitals that are left are overwhelmed.

Bashaer Hospital offers care and basic treatment free of charge.

However, the lifesaving medicines needed by the children in the malnutrition ward must be paid for by their families.

Masajed is a twin, she and her sister Manahil were brought to the hospital together. But the family could only afford antibiotics for one child.

Touma had to make the impossible choice – she chose Manahil.

"I wish they could both recover and grow," her grief-stricken voice cracks, "and that I could watch them walking and playing together as they did before.

"I just want them both to get better," Touma says, cradling her dying daughter.

"I am alone. I have nothing. I have only God."

Survival rates here are low. For the families on this ward the war has taken everything. They have been left with nothing and no means to buy the medicines that would save their children.

As we leave, the doctor says none of the children in this ward will survive.

Across the whole of Khartoum, children's lives have been rewritten by the civil war.

Reminders of the conflict lie strewn across Khartoum

What began as an eruption of fighting between forces loyal to two generals – army chief Gen Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and RSF leader Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti – soon engulfed the city.

For two years – until last March when the army retook control - the city was gripped by war as rival fighters clashed.

Khartoum, once a hub of culture and commerce on the banks of the River Nile, became a battlefield. Tanks rolled into neighbourhoods. Fighter jets roared overhead. Civilians were trapped between crossfire, artillery bombardments and drone strikes.

It is in this devastated landscape, amid the silence of destruction, that the fragile voice of a child rises from the rubble.

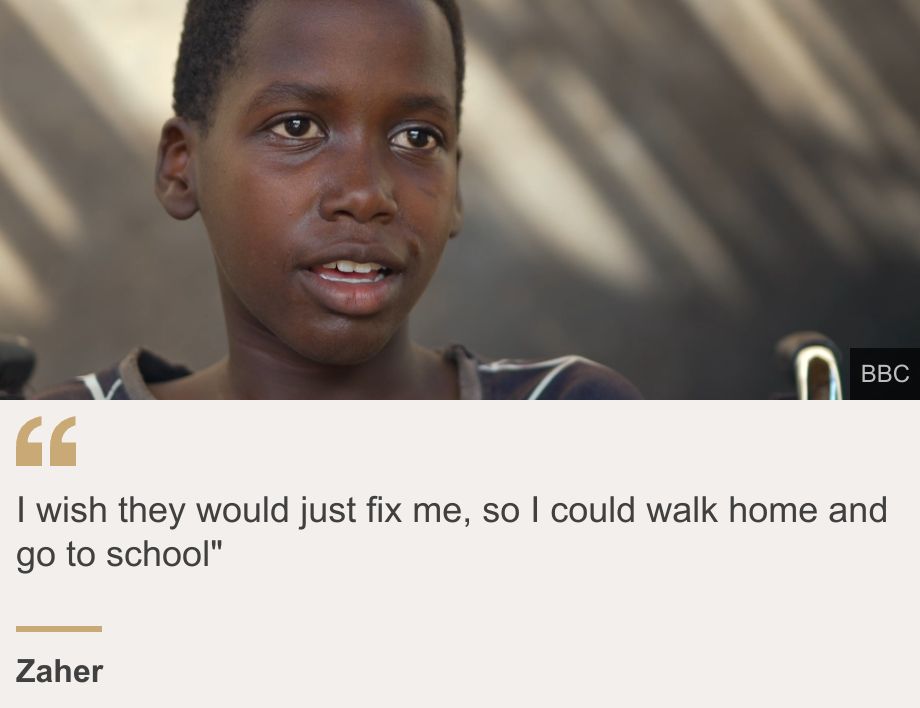

Twelve-year-old Zaher wheels himself through the wreckage, past burnt-out cars, tanks, broken houses and forgotten bullets.

"I'm coming home," he sings softly to himself as his wheelchair rolls over broken glass and shrapnel. "I can no longer see my home. Where's my home?"

Zaher still loves to play football

His voice, fragile but determined, contains both a lament for what has been lost and a quiet hope that one day, he may finally go home.

In a building now being used as a shelter, Zaher's mother Habibah tells me about what life was like under RSF control.

"The situation was very difficult," she says. "We couldn't switch on our lights at night - it was as if we were thieves. We didn't light fires. We didn't move at all at night."

She sits next to her son in a room lined with single beds.

"At any moment, whether you were sleeping or taking a shower, standing or sitting, you find them [the RSF] breathing down your neck."

Many fled the capital, but Zaher and his mother had no means to get out. To survive, they sold lentils on the streets.

Then one morning, as they worked side by side, a drone struck.

"I looked at him and he was bleeding. There was blood everywhere," Habibah says. "I was losing consciousness. I forced myself to stay awake because I knew if I passed out, I would lose him forever."

Zaher's legs were badly damaged. After hours of agony, they made it to hospital .

"I kept praying: 'Please God, take my life instead of his legs,'" she cries.

But doctors could not save his legs. Both had to be amputated just below the knee.

"He would wake up and ask: 'Why did you let them cut my legs?'" She looks down, her face filled with remorse, "I couldn't answer."

Both Habiba and her son weep, tormented by the memory of what happened to them. It is made worse by knowing that prosthetic limbs could give Zaher a chance at his old childhood, but Habiba cannot afford them.

For Zaher, the memory of what happened is too difficult to talk about.

He only shares one simple dream. "I wish I could have prosthetic legs so I can play football with my friends like I used to. That's all."

Children in Khartoum have been robbed not only of their childhoods but of safe places to play and be young.

Schools, football pitches and playgrounds are now shattered, with broken reminders of a life stolen by conflict.

"It was very nice here," says 16-year-old Ahmed looking around a destroyed funfair and playground.

Ahmed has found human remains at a playground where he is paid to tidy up

Printed on his grey, tattered T-shirt is a huge smiley face - the word "smile" emblazoned beneath it. But his reality could not be further from that sentiment.

"My brothers and I used to come here. We played all day and laughed so much. But when I came back after the war, I couldn't believe it was the same place."

Ahmed now lives and works here clearing the debris left by war, earning $50 (£37) for 30 days of continuous labour.

The money helps support him, his mother, grandmother and one of his brothers.

There were six other brothers but, like so many in Sudan who have missing family members, he has lost contact with them. He looks at his feet as he tells us he doesn't know where they are or if any are still alive.

The war has ripped families like his apart.

Ahmed's work reminds him of that nearly daily. "I have found the remains of 15 bodies so far," he says.

Many of the remains found here have since been buried, but there are still some bones lying around.

Ahmed walks across the park and picks up a human jaw. "It's terrifying. It makes me shake."

He shows us another bone and holding it innocently beside his leg, he says: "This is a leg bone, like mine."

Ahmed says he no longer dares to dream of a future.

"Ever since the war began, I have been certain that I was destined to die. So I stopped thinking about what I would do in the future."

I wish they would just fix me, so I could walk home and go to school"

The destruction of schools has put the future of children in even more jeopardy.

Millions are no longer being educated.

But Zaher is one of the lucky few. He and his friends attend school in a makeshift classroom set up by volunteers in an abandoned home.

They call out answers loudly, write on the board, sing songs and there are even a few naughty kids messing around at the back of the class.

Hearing the sound of children learning and laughing, in a country where places to be a kid are so limited, is like nectar.

When we ask what childhood should be like, Zaher's classmates answer with innocence still intact: "We should be playing, studying, reading."

But the memory of war is never far away. "We shouldn't be afraid of the bombs and the bullets," interrupts Zaher. "We should be brave."

Their teacher, Miss Amal, has taught for 45 years. She has never seen children so traumatised.

"They've been really affected by the war," she says.

"Their mental health, their vocabulary. They are speaking the language of the militias. Violent curse words, even physical violence. They carry sticks and whips, wanting to hit someone. They have become so anxious."

The damage extends beyond behaviour.

With most families stripped of income, food shortages are biting.

"Some students come from homes with no bread, no flour, no milk, no oil, nothing at all," the teacher says.

And yet, amid despair, Sudan's children cling to fleeting moments of joy.

On a scarred football pitch, Zaher drags himself across the dirt on his knees, determined to play the game he loves most. His friends cheer him on as he kicks the ball.

"My favourite thing to do is football," he says, smiling for the first time.

When asked which team he supports, the answer is immediate: "Real Madrid." His favourite player? "Vinícius."

Playing on his knees is extremely painful and could lead to more infections. But he doesn't care.

Football and his friendships have saved him. They have brought him joy and an escape from his reality. Yet, he dreams of prosthetic legs.

"I wish they would just fix me, so I could walk home and go to school," Zaher says.

Additional reporting by Abdelrahman Abutaleb, Abdalrahman Altayeb and Liam Weir

More BBC stories on the conflict in Sudan:

A pregnant woman's diary of escape from war zone: 'I prayed the baby wouldn't come'

Oil-rich Sudanese region becomes new focus of war between army and rival forces

Medics under siege: 'We took this photo, fearing it would be our last'

'Our children are dying': Rare footage shows plight of civilians in besieged Sudan city

Go to BBCAfrica.com, external for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

BBC Africa podcasts

- Attribution