Husband guilty in murder case without a body that shocked France

Defence lawyers said Cédric Jubillar had just found out his wife had begun an affair when she disappeared

- Published

A murder trial without a body which transfixed France has ended with 38-year-old painter-decorator Cédric Jubillar being convicted of killing his wife.

Throughout the four-week trial, Jubillar maintained his innocence but was found guilty by a jury and sentenced to 30 years in jail.

In four weeks of hearings in the southern town of Albi, the defence argued that because the body of his wife Delphine had never been found there was no certainty a crime had been committed.

But the jury of six civilians and three magistrates decided that there was enough circumstantial evidence to conclude that Jubillar was guilty of murder.

Jubillar's lawyers have said they will appeal.

"We respect the jury's decision," said defence lawyer Alexandre Martin. "Of course we're disappointed, but we knew there would be a second battle, and we will get back to work on this appeal.

"Delphine was killed by her husband's hands," said Laurent Boguet, acting for the couple's two children. It was now for Jubillar to "tell us where his wife's remains are and return them to the family".

Jubillar's lawyers Alexandre Martin (L) and Emmanuelle Franck were shocked by the verdict

With its central mystery of his wife's missing body, the case has been hotly followed across news and social media since it broke five years ago. Amateur detectives proliferated online, much to the annoyance of police and families, with theories of what happened.

It was on the night of 15-16 December 2020, in the middle of the Covid pandemic, that 33-year-old Delphine Jubillar disappeared from the house in Cagnac-les-Mines where the couple lived with their two children aged six and 18 months.

Cédric Jubillar contacted police at around 04:00 on 16 December to say he had been woken up by the crying of the younger child and discovered that his wife had gone missing.

Police and neighbours conducted extensive searches in the local area – including in its many abandoned mines – but no body was ever found.

The court heard during the trial how Cédric and Delphine's relationship had turned sour. She had asked for a divorce, and was beginning an affair with a man she met over a chatline.

According to the prosecution, on the evening of her disappearance she had told Cédric Jubillar for the first time that she had taken a lover. This led to a row – during which Delphine's screams were heard by a neighbour – and then he killed her, probably by strangling.

Jubillar was then said to have disposed of her body somewhere in the countryside nearby, which he knew well.

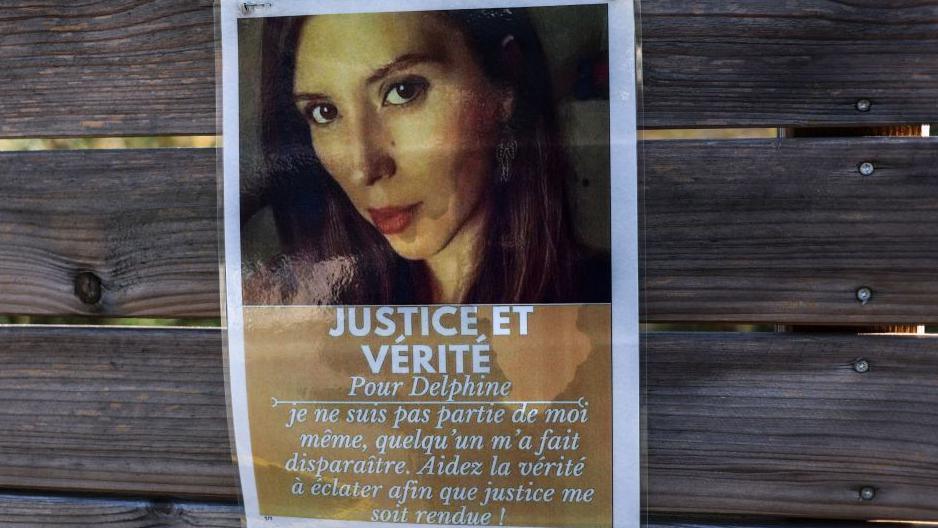

A poster of Delphine Jubillar posted on a wall some time after her death

A key piece of evidence was that Delphine's car on the street outside was facing in the opposite direction from the way she normally parked it, suggesting he had used it on the night.

Other key elements were:

a broken pair of Delphine's glasses in the sitting-room

the lack of steps recorded on Jubillar's phone pedometer, even though he claimed to have been out searching for his wife

and a statement by their son Louis about an argument between his parents taking place "between the sofa and the Christmas tree".

Psychological assessments presented Jubillar as a feckless character with a rough childhood, who smoked marijuana every day, had difficulty holding down a job and thought of little but his own personal gratification.

He was said to have shown little concern over the disappearance of Delphine – drawing money from her bank account a short time later, for example.

And there was crucial evidence from Cédric Jubillar's mother, who recalled him telling her when he first heard that Delphine wanted a divorce: "I've had enough. I'm going to kill her and bury her, and they'll never find her."

Jubillar's defence lawyer Emmanuelle Franck said none of this amounted to more than speculation – and that the accused's habits and attitudes could not be taken as signs of criminal responsibility.

"Courts do not convict bad characters. They convict the guilty," she said.

According to the defence, there were alternative explanations for all the circumstantial clues. They said witnesses had been coached by investigators, in order to corroborate the theory of guilt.

They argued that in any normal crime of passion, there were tell-tale signs left at the scene – blood, or evidence of a clean-up. But all this was absent from the Jubillar home.

His lawyers said that details told in court of Cédric Jubillar's behaviour were all irrelevant: his use of pornography, a pair of panda pyjamas with ears and tail that he was wearing when police came, and making his son Louis sit on Lego bricks as a punishment.

"Either [Cédric] is a criminal genius, or he is a bit of an idiot – you have got to decide," said Emmanuelle Franck.

The defence offered no alternative explanation for Delphine's disappearance.

Convictions for murder without a body are rare because of the difficulty of proving the existence of a crime. But they do happen, with jurisdictions in many countries concluding that circumstantial evidence alone can constitute proof.

For a guilty verdict in France, jurors need to have an "intimate conviction" that a crime has been committed – a concept that is left vague in law. If more than two of the nine jurors dissent, then the accused is found not guilty.