The builder who photographed distant galaxies

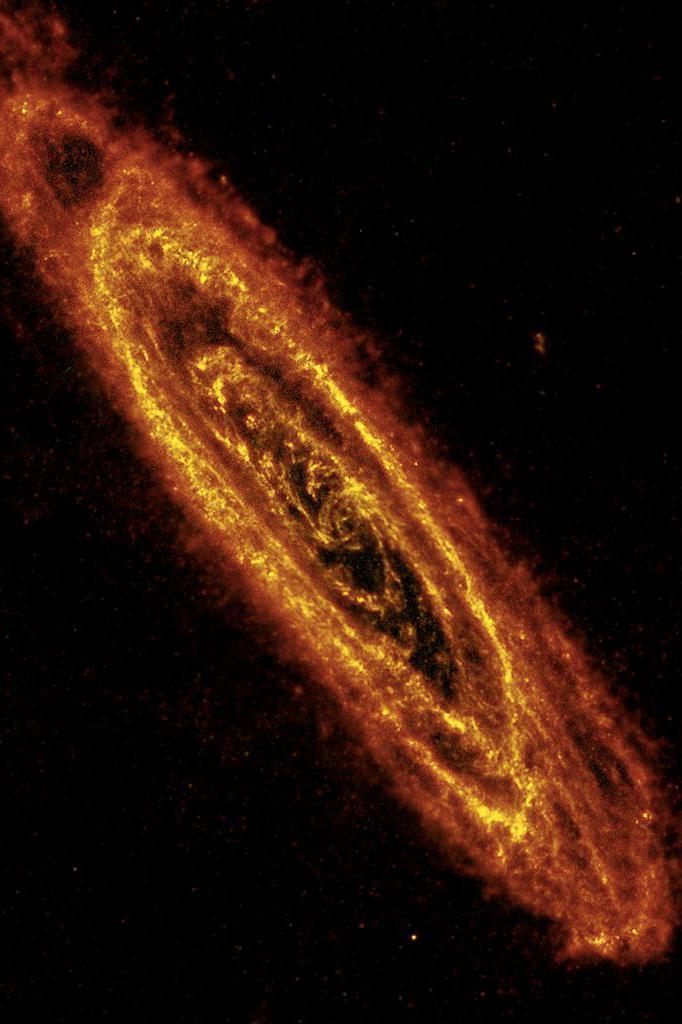

Isaac Roberts was the first person to take a clear image of our nearest large galaxy, Andromeda, 2.5 million light years away

- Published

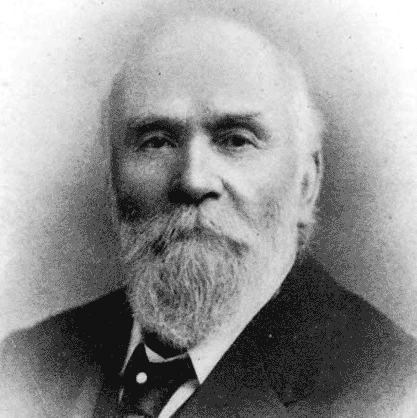

A successful builder by day and traversing the sky by night, Isaac Roberts took the first clear photograph of Andromeda, the closest galaxy to our Milky Way.

Mr Roberts, born in 1829 and the son of a farmer at Groes-bach Farm near Denbigh, took the photograph in 1888, revealing its distinctive spiral structure and mysterious dark lines to a doubting world.

He worked as a builder in Liverpool, having moved there aged seven, then spent the latter part of his life as a neighbour of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle at Crowborough in Sussex.

But his telescope revealed far more mysteries than Sherlock Holmes could ever have dreamt.

Isaac Roberts demonstrated the spiral structure of galaxies

According to W.A. Evans, writing in a 1969 edition of the Denbighshire Historical Society Transactions, Mr Roberts became a Sunday School teacher and "made strenuous efforts to make up for his early lack of education by attending the Liverpool Mechanics Institute classes in geology, chemistry, electricity and astronomy".

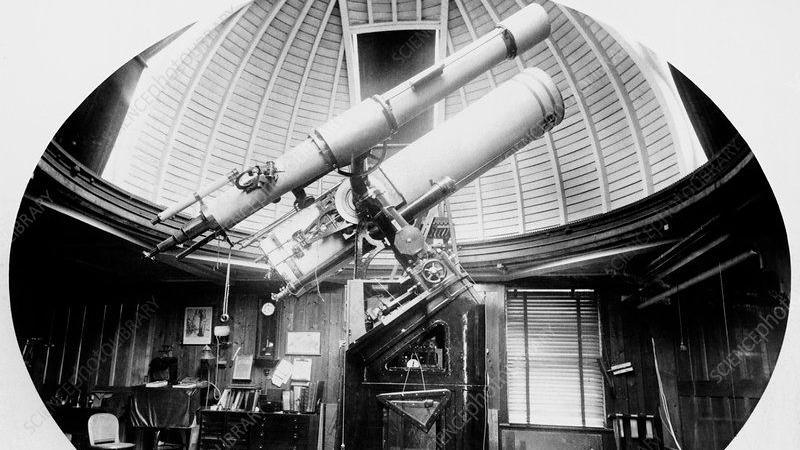

Isaac Roberts built an observatory in Merseyside, capable of reaching into deep space

His early scientific interests were closely related to his profession in the construction industry, presenting geological papers on the drainage of water through sandstone and the difficulties of building on these surfaces.

However, as he established himself as a master builder, he gradually found himself with more time to pursue his loftier ambitions.

His Rock Ferry observatory near Birkenhead was equipped with a telescope containing a 20" reflecting mirror made from silver-coated glass, mounted with a 7" refractor as a tracking scope, attached to a camera which produced images on glass plates.

14-year-olds win Young Astronomy Photography award

- Published20 September 2022

Stargazing photographer shares sense of wonder

- Published10 November 2024

Welsh island has been made a dark sky sanctuary

- Published23 February 2023

While these components were bought in from other manufacturers, it was a device purely of his own invention which made his photos of the night sky stand out from those which had gone before.

Evans wrote: "The important innovation was a clockwork mechanism which could keep the telescope sighted at the same point in the night sky for 105 minutes.

"This was a most intricate mechanism and resulted in far more accurate observations. The photographs obtained by this method of sighting showed 1,270 stars in the North Pole cluster, compared to the 38 in previous photographs."

The 105 minutes was the key figure, as this was the amount of time it took for photographic images to be exposed onto the glass panels available to Mr Roberts at the time.

Stephen Eales, professor of astronomy at Cardiff University, said this contraption was the first to solve a problem which scientists still wrestle with to this day.

"The advantage of photography over the naked eye is that light can accumulate on film over time, allowing objects to be seen in far more detail than in just one snapshot.

"However the down side is that the Earth is rotating so quickly that in a matter of seconds you will have lost your focus on the target.

"Nowadays telescopes are programmed by computer to counteract the Earth's rotation, but to have come up with a mechanical solution to this problem so early was revolutionary."

In 2010 Prof Eales' team built a camera onboard the William Herschel Space Observatory, which captured the very same image as Isaac Roberts had 122 years before. The observatory - in Earth's orbit, four times more distant than the moon - only lasted from 2009 - 2013, before the helium cylinders required to cool it to near absolute zero ran out

Prof Eales first became interested in Mr Roberts when writing his own book The Ghost in The Telescope, on how his team had observed the same Andromeda Galaxy through the William Herschel Space Observatory in 2010.

"We were investigating Andromeda in the submillimetre waveband, between infrared and radio waves - that allowed us to see what causes the dark lines visible in Roberts' photos, which many had written off as imperfections in his exposure.

"In the visible wavelengths you can only see a 'stellar bulge' of old stars, but the newly-born stars are masked by interstellar dust."

Prof Eales likened it to looking at a bonfire through its smoke.

"The new stars are there, glowing blue as opposed to the older stars' red, but Isaac couldn't picture them because they were masked by the 'smoke' of their creation. We were able to prove their existence by measuring the tiny difference in radiation between the dark lines Isaac photographed and the space around them."

Installed first at his home near Liverpool, Roberts' telescope was later moved to the less smoky skies of Crowborogh, Sussex

Prof Eales believes it was the collision of photography and astronomy during the late 19th Century which made this all possible.

"People had been staring into space for centuries, but without a means of recording what they'd seen, it was impossible to cross-check their findings.

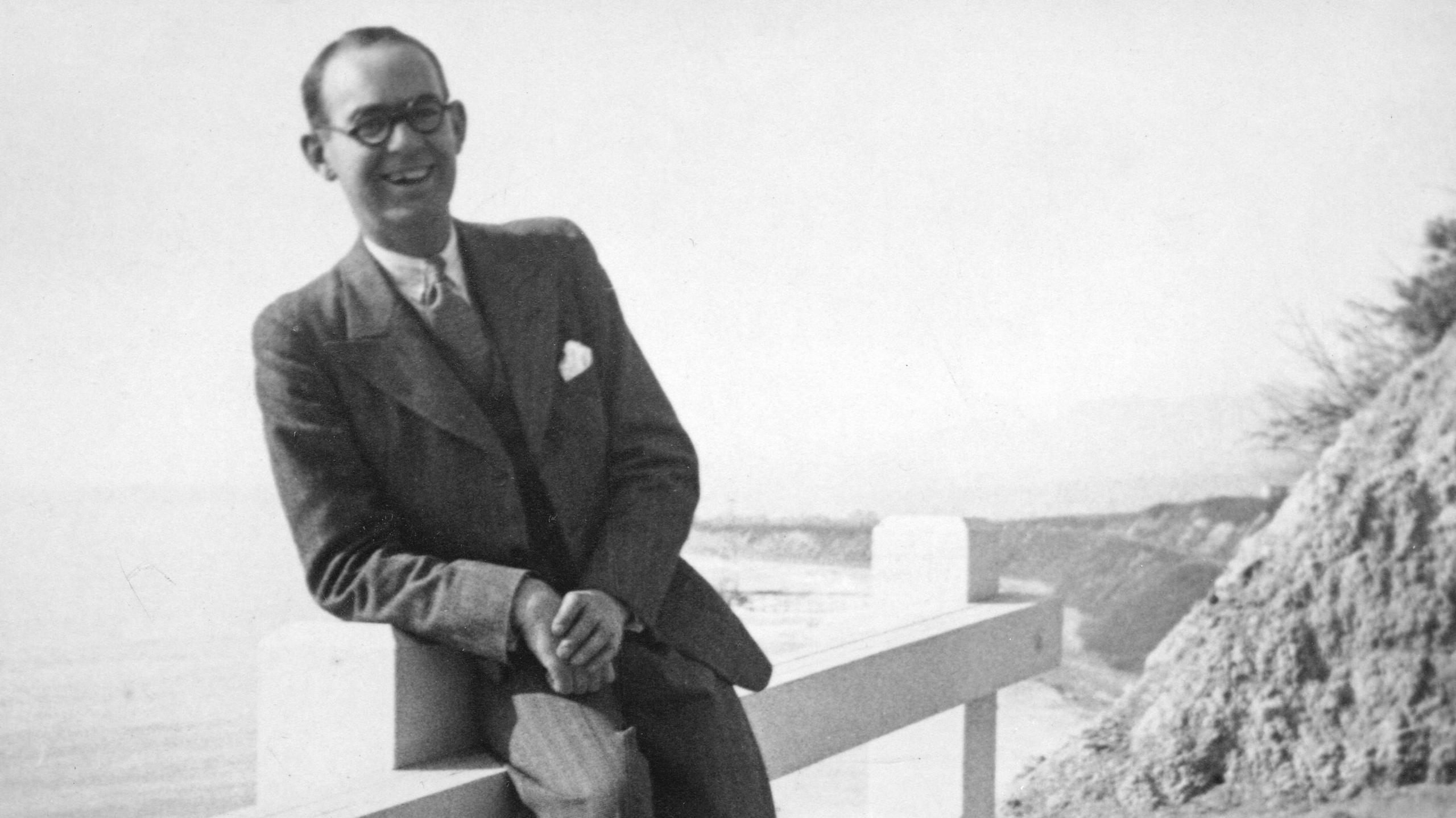

"Isaac, along with Edward Emerson Barnard in America, were amongst the first to put the disciplines together.

"Barnard was a brilliant self-taught photographer who'd been forced into work at the age of six through poverty, and Isaac had mastery of the skies. It was by people like this coming together and sharing their knowhow that we have the foundations upon which research like ours with the William Herschel Space Observatory were built."

Roberts' 'Starfield' home, where he lived cheek by jowl with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, but did he ever detect the dog who barked in the night?

Shortly after his groundbreaking 1888 photograph Roberts relocated to Sussex to escape Liverpool's pollution; partly owing to his chronic bronchitis, and partly in search of clearer skies.

In the village of Crowborough he would almost certainly have rubbed shoulders with neighbour Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, though no documentary evidence has been found that the two were familiar.

In 1896 he was a member of the party who went to Vadso in Norway to observe the total eclipse of the sun, where he met his future second wife Dr Dorothea Klumpke of the Paris Observatory.

32 years his junior, Dorothea was by Roberts' side throughout the latter years of his life, from 1896 to 1904

In his remaining years the pair set about fulfilling astronomy pioneer William Herschel's "bucket list", photographing the constellations which Herschel knew of before his death, but had not been able to capture for himself on film.

In 1929, some 25 years after Roberts' death, his widow published their joint findings in "Isaac Roberts' Atlas of 52 Regions, a Guide to William Herschel's Fields of Nebulosity".

In the last years of his life he was awarded a D.Sc by Trinity College Dublin, and given a gold medal as a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society.

He left a scholarship of £40,000 to the universities of Wales and Liverpool.

His old Liverpool friend Eleazar Roberts wrote that he often quoted the Welsh hymn: "Mae'n llond y nefoedd, llond y byd," or as it translates into English: "It's full of heaven, full of the world."

Related topics

- Published7 September

- Published3 August

- Published27 July