Why Starmer’s NHS reforms may give you a sense of deja-vu

- Published

Across more than 150 pages, NHS surgeon and independent peer Lord Darzi sets out in clear, painstaking detail the failings of the NHS in England.

But that is the easy bit – fixing it is an altogether different challenge.

The government is promising the "biggest reimagining” of the NHS since it was formed. A 10-year plan is expected in the spring.

And there are hints about what that will mean in what the prime minister said in his speech on Thursday – a digital revolution, moving care out of hospitals and into the community and a greater emphasis on preventing people becoming ill in the first place.

But you could be forgiven for feeling a sense of deja-vu about such ideas - these are all things that have been talked about for the past 20 years.

In fact, Lord Darzi produced a report recommending just this in 2007, when he was working for the Blair government.

In response to Lord Darzi's report, Sir Keir Starmer promised major reform

So why has it not happened? Lord Darzi is critical of changes to the NHS made by the coalition government in 2012, which saw a big shake-up of management structures.

This had been disastrous, he said, and distracted the NHS at a time when it had been trying to cope with austerity and the tightest budget settlement in its history.

But that does not fully explain the current situation.

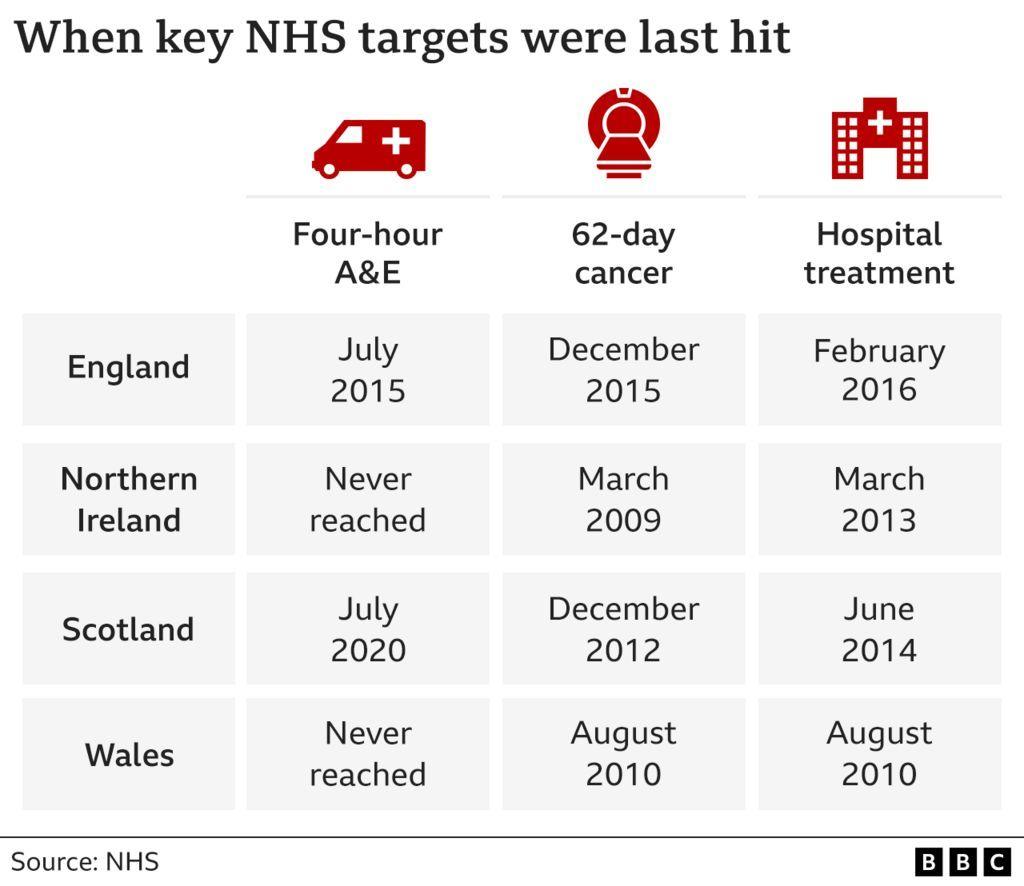

After all, that shake-up was in England only but the rest of the UK is also struggling to meet its waiting-time targets - and in the case of Wales and Northern Ireland, even more so.

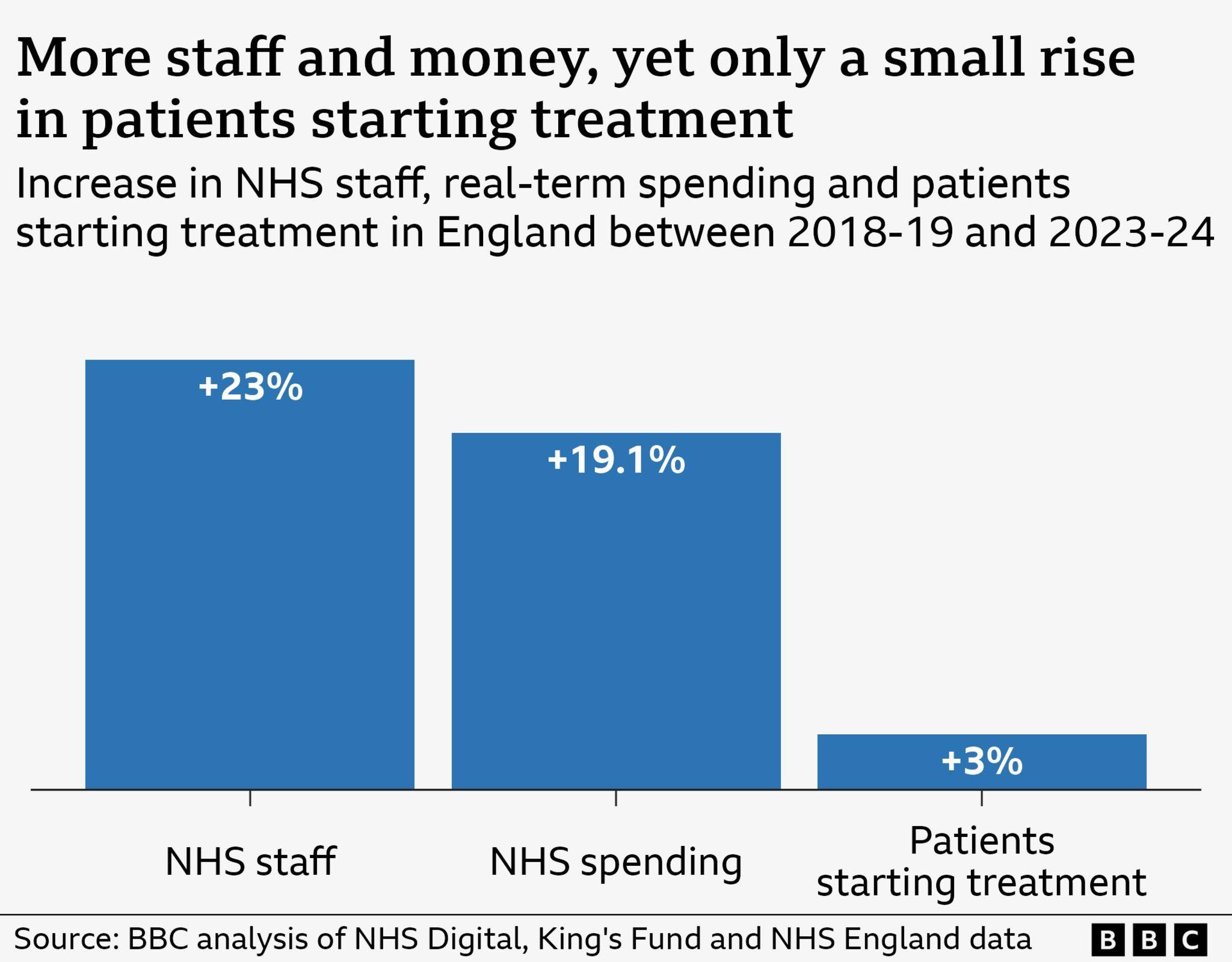

The Tories have quite rightly pointed out that despite the squeeze in spending on public services, the NHS still saw its budget increase by more than inflation.

But successive administrations found the money kept being swallowed up by ever-increasing day-to-day demands. It was running just to standstill. And when the pandemic hit, it started going backwards - quickly.

Lord Bethell, a Conservative health minister in the Boris Johnson government, has admitted more could have been done - but the Department of Health found it “impossible to persuade the Treasury” it would see a return on investment by ploughing more money in.

And while there is now a completely new government, all the signs are the Treasury will still be playing hardball.

Indeed, the prime minister himself said there would be “no more money without reform”.

But the problem, as the likes of Matthew Taylor, the head of the NHS Confederation, which represents NHS trusts, points out, is that requires significant upfront capital investment in buildings, technology and equipment.

Lord Darzi’s new report makes this clear, saying £37bn extra would have been invested in capital if the NHS had kept up with spending levels of similar countries during the 2010s.

Instead, it has been left with crumbling hospitals, operations being performed in portacabins and a fifth of GP premises predating the formation of the NHS, in 1948.

With the next winter crisis no doubt just around the corner and the health service already accounting for more than 40p out of every £1 spent on the day-to-day running of public services, it is easy to see why turning the NHS around is arguably the biggest challenge facing the new government.