Listen to Dan read this article

When dairy farmer Patrick Holden sat down at his kitchen table to read his emails one day in July, he couldn’t believe his luck. A buyer, who claimed to represent a French supermarket chain, wanted to buy 22 tonnes of Hafod, his specialist cheddar.

“It was the biggest order for our cheese we’ve ever received,” he recalls, “and, because it was from France, I thought, ‘finally, people on the continent are appreciating what we do’.”

The order had been made through Neal’s Yard Dairy, an upmarket cheese seller and wholesaler, and the first batch of Hafod arrived at its London base in September. It took up just one square metre on a pallet but represented two years of effort and had a wholesale value of £35,000.

“It’s one of the most special cheeses being made in the UK,” explains Bronwen Percival, a buyer at Neal’s Yard Dairy. Once bound in muslin cloth and sealed with a layer of lard, Hafod is aged for 18 months.

The farm didn’t have enough to fulfil the order, so 20 tonnes of Somerset cheddar was also provided by two other dairy farms to make it up; in all, this was £300,000-worth of some of the most expensive cheese made in the UK.

On 14 October, it was collected from Neal’s Yard’s warehouse by a courier and taken to a depot – and then, mysteriously, it disappeared.

There had, in fact, been no order. It came instead from someone impersonating the supposed buyer.

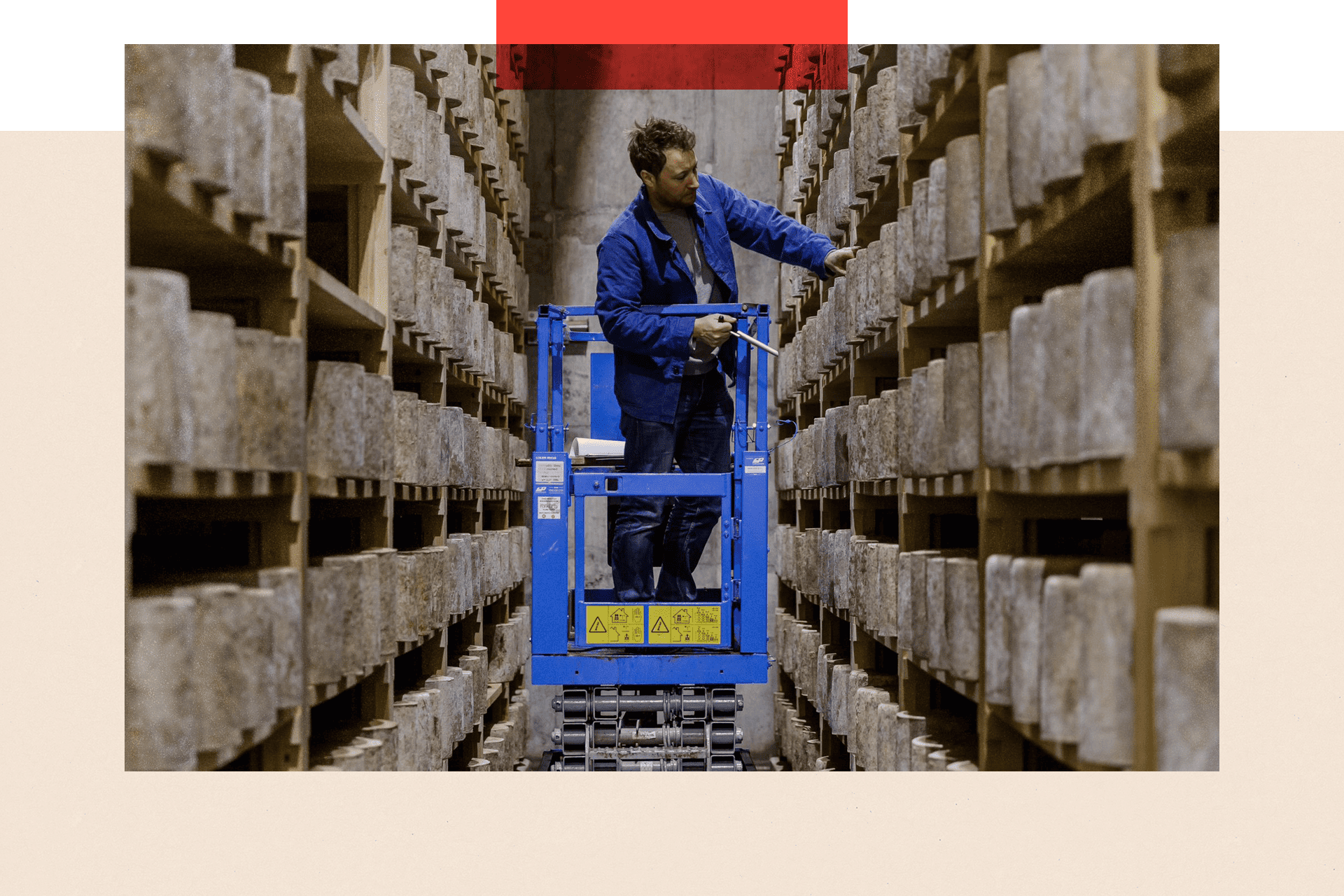

Tom Calver of Westcombe Dairy in Somerset - some of his cheese was in the stolen consignment

The theft made global headlines, and was nicknamed “the grate cheese robbery”. British chef Jamie Oliver warned his followers on X: “If anyone hears anything about posh cheese going for cheap, it’s probably some wrong’uns.”

In late October, a 63-year-old man was arrested in London, then released on bail. And there has been no news since. The 950 truckles of cheese – roughly the weight of four full-sized elephants – have disappeared without a trace.

“It is ridiculous,” says fellow cheesemaker Tom Calver, whose cheddar was part of the stolen consignment. “Out of all the things to steal in the world – 22 tonnes of cheese?”

And yet it isn’t as surprising as it at first seems – for this is far from the first theft of its kind.

Why cheese theft is on the rise

Food-related crimes – which include smuggling, counterfeiting, and out-and-out theft – cost the global food industry between US $30 to 50 billion a year (£23-£38 billion), according to the World Trade Organisation. These range from hijackings of freight lorries delivering food to warehouses to the theft of 24 live lobsters from a storage pen in Scotland.

But a number of these food crimes have also targeted the cheese industry – and in particular luxury cheese.

Last year, in the run-up to Christmas, around £50,000 worth of cheese was stolen from a trailer in a service station on the M5 near Worcester. The problem isn't a new one - as far back as 1998, thieves broke into a storeroom and took nine tonnes of cheddar from a family-run farm in Somerset.

It’s happening elsewhere in Europe, too: in 2016, criminals made off with £80,000 of Parmigiano Reggiano from a warehouse in northern Italy. This particular type of parmesan, which requires at least a year to mature, is created by following a process that has been in place, with little modification, for almost 1,000 years. At the time of the heist, Italy’s Parmigiano Reggiano Consortium told CBS news that about $7 million (£5.4m) worth of cheese had been stolen in a two-year period.

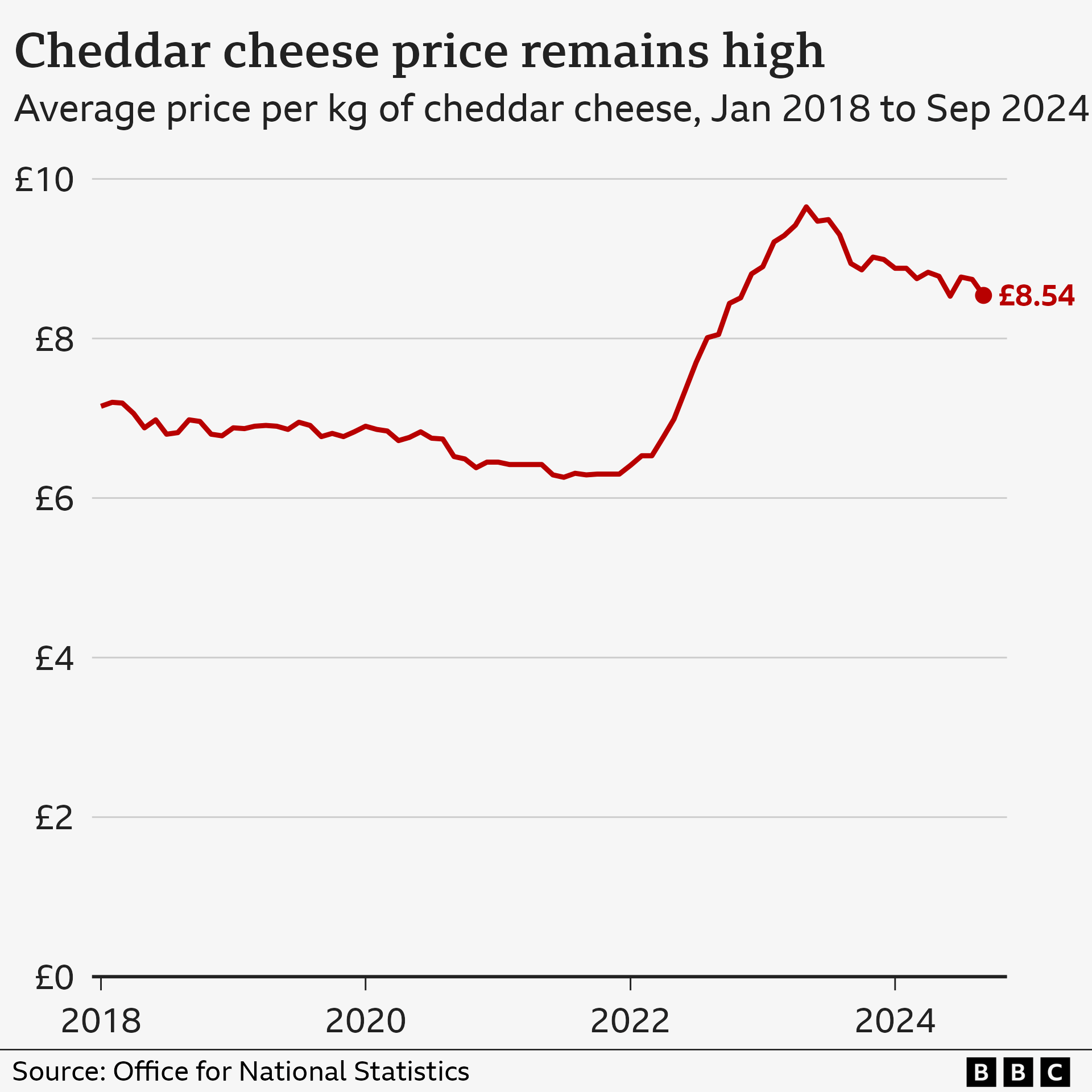

The problem is only set to rise across the industry as cheese becomes more valuable. The overall price of food and non-alcoholic drinks in the UK rose around 25% between January 2022 and January 2024, according to the Office for National Statistics. Cheese, meanwhile, saw a similar price hike in the space of a single year.

High prices are increasingly making cheese a target of theft

“Cheesemaking is an energy-intensive business,” says Patrick McGuigan, a specialist in the dairy sector. This is because in the production process milk needs to be heated up and, once made, cheese is stored in energy-hungry refrigerators, meaning that fuel prices play a big part in the cost. “And so there was a big price increase following the disruption caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.”

In 2024, overall food price inflation in the UK has fallen to 1.7 per cent, but less so for cheese. “The retail price of cheddar increased by 6.5 per cent up to May 2024,” adds McGuigan. “This is why we’re seeing security tags on blocks of cheddar in supermarkets. Based on price alone, cheese is one of the most desirable foods a criminal can steal.”

Yet it isn’t the easiest product to shift – particularly farmhouse cheese, most of which tends to be heavy and bulky and must be kept at specific temperatures. As such, transporting it can be a costly, complicated procedure that is beyond most criminals – unless, of course, they are organised.

But the question that remains is who exactly these organised criminals are – and where does the cheese end up?

How organised crime infiltrated the food industry

“There is a long-established connection between food and organised crime,” says Andy Quinn of the National Food Crime Unit (NFCU), which was established in 2015 following the 2013 horse meat scandal. One example of this is the high proportion of illegal drugs smuggled through legal global food supply chains.

In September, dozens of kilograms of cocaine were found in banana deliveries to four stores of a French supermarket, with police unsure who the intended recipient was. For the drugs to reach the end of the food supply chain is highly unusual, but this method of transporting illegal items across borders in containers of food is common.

According to Quinn, once drug cartels and other criminal operators gain a foothold into how a food business operates, they spot other opportunities. “They will infiltrate a legitimate business, take control of its distribution networks and use it to move other illegal items, including stolen food.”

For criminal networks, food has other attractions. “They know crimes involving food result in less severe convictions than for importing drugs,” says Quinn, “but they can still make similar amounts of money.” Particularly if it’s a premium cheese.

The problem for the criminals is what to do with it. “There are few places to offload them,” says Jamie Montgomery, who runs the Somerset farm that was targeted in the 1998 heist. “Shifting that much artisan cheese is difficult.”

This is why people in the industry believe stolen cheese is often sent overseas to countries where there are thriving food black markets – and indeed cheese black markets.

'Fromagicide' and the overseas black market

Russia is one country where there is a thriving black market for cheese. Following the illegal annexation of Crimea in March 2014, the EU and other states imposed economic sanctions on Russia. President Vladimir Putin responded by banning fresh produce from the countries behind the sanctions.

State television made a great show of the ban by broadcasting footage of foreign food being bulldozed, buried or burned, including huge cheeses being dumped and crushed.

Soon the so-called "fromagicide" was worldwide news.

The Russian government began confiscating banned food at the border and publicly destroying it

Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, sanctions have been further tightened and the availability of certain food from the West has become even more limited, among them Scottish whisky and Norwegian salmon. At the same time, the black market in Russia for high-end foods from the EU has been growing.

“Cheese and wine are two of the most common products being transported illegally into Russia,” says Professor Chris Elliott, founder of the Global Institute for Food Security and a senior scientific advisor to the UN, “and there are sophisticated routes across Europe’s borders through Belarus and Georgia”.

Many Russians feel that the quality of local cheese doesn’t compare to banned foreign goods, so there is wide demand. Indeed, after the ban, some resorted to extreme measures – one man was caught attempting to drive into Russia from Poland with 460kg of banned cheese on the backseat of his car.

Since 2014, expensive and complex varieties of cheese from countries that were not previously known for their cheese have appeared on shop shelves, such as Belarusian camembert and parmesan. Some companies import European cheese to Belarus or other CIS countries, where the label is swapped so that it can be sold legally in Russian shops.

There were also reports of corner shops becoming black market cheese dealers.

Corruption makes the movement of sanction-busting food possible, says Prof Elliott. “So much money is involved that officials, including border guards, can be paid off. Sanctioned goods are bought and sold through digital networks and these online orders also make it into shops.”

Why Britain’s biggest unsolved mass murder is being revisited 50 years on

- Published4 November 2024

The real reason for the rise in male childlessness

- Published1 November 2024

What the US election outcome means for Ukraine, Gaza and world conflict

- Published29 October 2024

Paul Thomas spent years running cheesemaking courses in Russia. When he visited Moscow after the sanctions were tightened, he observed firsthand that banned cheeses were being displayed openly on the shelves of shops. “There was plenty of authentic Italian Parmigiano Reggiano and French Roquefort, all clearly labelled”.

He also observed that cheesemakers in Russia have been boosting production and attempting to emulate types of European cheese.

It’s not just Russia – in various parts of the Middle East, for example, food subsidies in one country can provide an incentive to smuggle ingredients into others where governments provide no support and prices are high. Counterfeiting, or creating a replica of an official type of cheese, is also common in the region.

And in the US, strict federal rules mean it’s illegal to produce or import unpasteurised cheeses aged for less than 60 days, leading to a black market for raw-milk products such as French classics Brie de Meaux and Mont d’Or. In 2015, a raw-milk trafficking gang was prosecuted for distributing unpasteurised cheeses.

Food counterfeiting also happens in the US – in some cases, cheap and even dangerous ingredients are being used to produce “fake” versions of expensive cheese, such as parmesan made using additives derived from wood pulp.

Microchipped parmesan: Innovative security

Andy Quinn explains: “Food chains are truly global. The same goes for the movement of illegal food.”

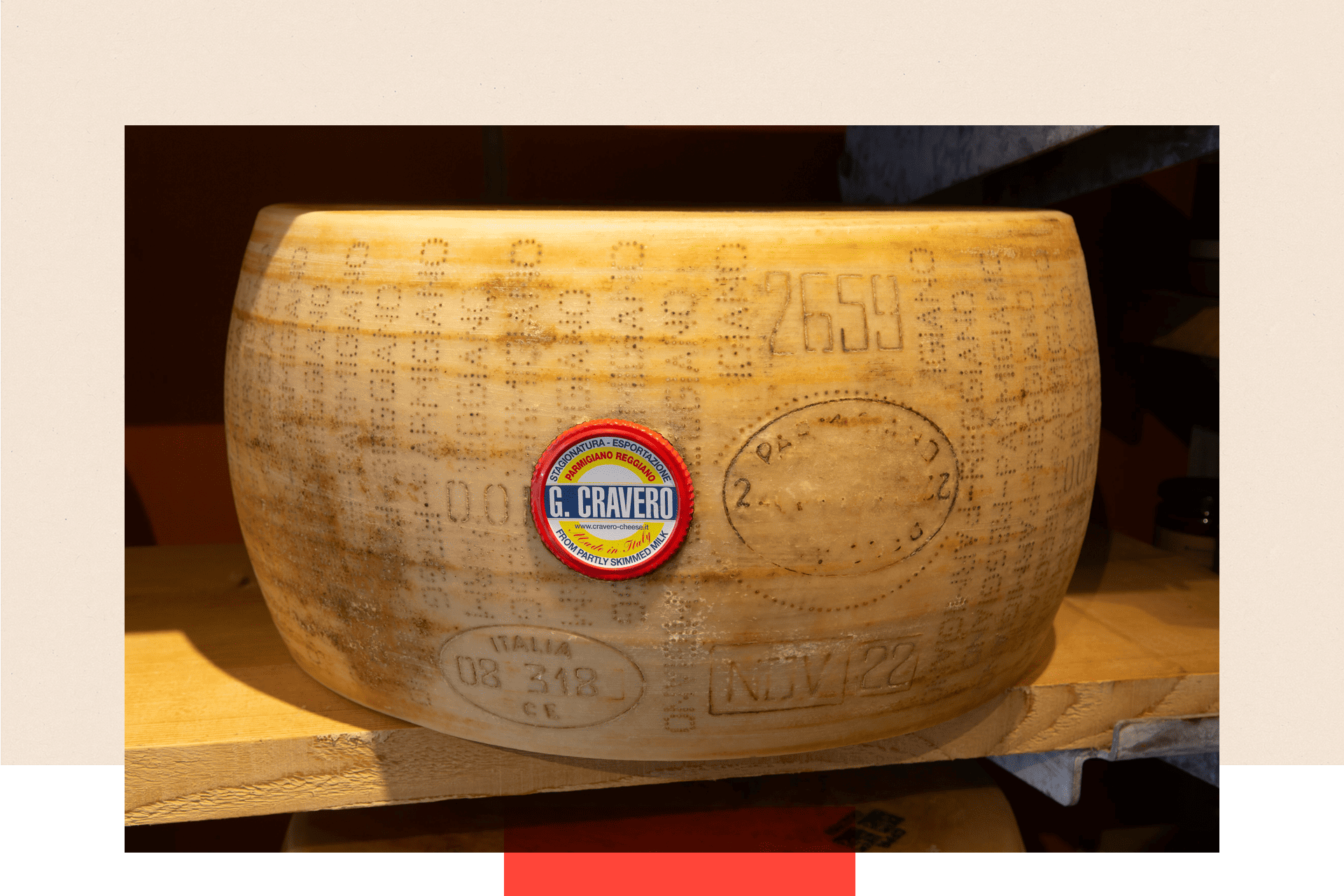

Now, many in the industry are fighting back, however. Italy’s Parmigiano Reggiano Consortium – the cheesemakers behind the world’s most stolen cheese – have said that the black market for that variety is “robust”. This is partly down to the fact that it is hugely valuable, generating global sales of almost £3bn a year – and so they have come up with a unique way of protecting it.

In 2022, the consortium began introducing tracking chips, no larger than a grain of rice, as part of the label embedded in the hard rind of the cheese. This helps to reduce thefts, but also means counterfeit Parmigiano Reggiano can be identified, as each tiny chip contains a unique digital ID that can authenticate the cheese.

Buyers can now scan each wheel to check its authenticity or find out if it was stolen. The consortium is yet to release any figures showing whether the technology is cutting down levels of fraud.

Authentic Parmigiano Reggiano (pictured) is highly prized – but the value of fake parmesan sold is estimated to be about £2bn a year

Neal’s Yard Dairy says it plans to use a less high-tech approach to preventing future fraud, including visiting buyers in person when big cheese orders are made, rather than relying on digital contracts and emails.

As for what will become of the cheddar stolen in the October heist, there may be no swift solution: given that they could easily be stored for as long as two years, the cheese could still surface many months from now.

“A criminal could hide tonnes away and then pass them slowly, truckle by truckle, into supply chains,” says Ben Lambourne of the online retailer Pong Cheese.

For the cheesemakers, this isn’t just about a stolen food; the missing Hafod, Westcombe and Pitchfork represent ways of farming and food production that took thousands of years to evolve, shaped landscapes and became part of British culture, yet which have been all but lost in just a few generations.

Lancashire-based cheesemonger Andy Swinscoe says that at the beginning of the 20th Century, in the area surrounding his shop there were 2,000 farmhouse cheesemakers. Today, there are just five. There have been declines in Somerset with cheddar makers, in the East Midlands with Stilton and in the north-west with Cheshire cheese.

“It would be impossible for these small family farms to survive by selling liquid milk,” says Swinscoe – but they can add value by turning their milk into a farmhouse cheese.

Patrick Holden admits that the financial loss from this theft would have had a huge impact on his farm. “A fraud of this scale can easily spell the end of a farm and cheesemaking.” In this instance, Neal's Yard paid its suppliers in full, describing the effect of the fraud on their business as “a significant financial blow”.

Unless crimes like this are stopped, however, other farms and businesses will suffer similar blows, particularly when luxury cheese remains sought-after and prized.

“Conflicts around the world, the cost-of-living crisis, even climate change, all increase the appeal for food fraud,” says the NFCU’s Andy Quinn. Until that changes, cheesemakers might need to tighten up their security – and think twice when an order seems too good to be true.

Additional reporting by Olga Shamina, BBC News Russian.

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think - you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.

Get in touch

InDepth is the home for the best analysis from across BBC News. Tell us what you think.