What are the big security threats coming down the track?

Keir Starmer's government could face a range of security issues from a war in Lebanon to Russia winning in Ukraine

- Published

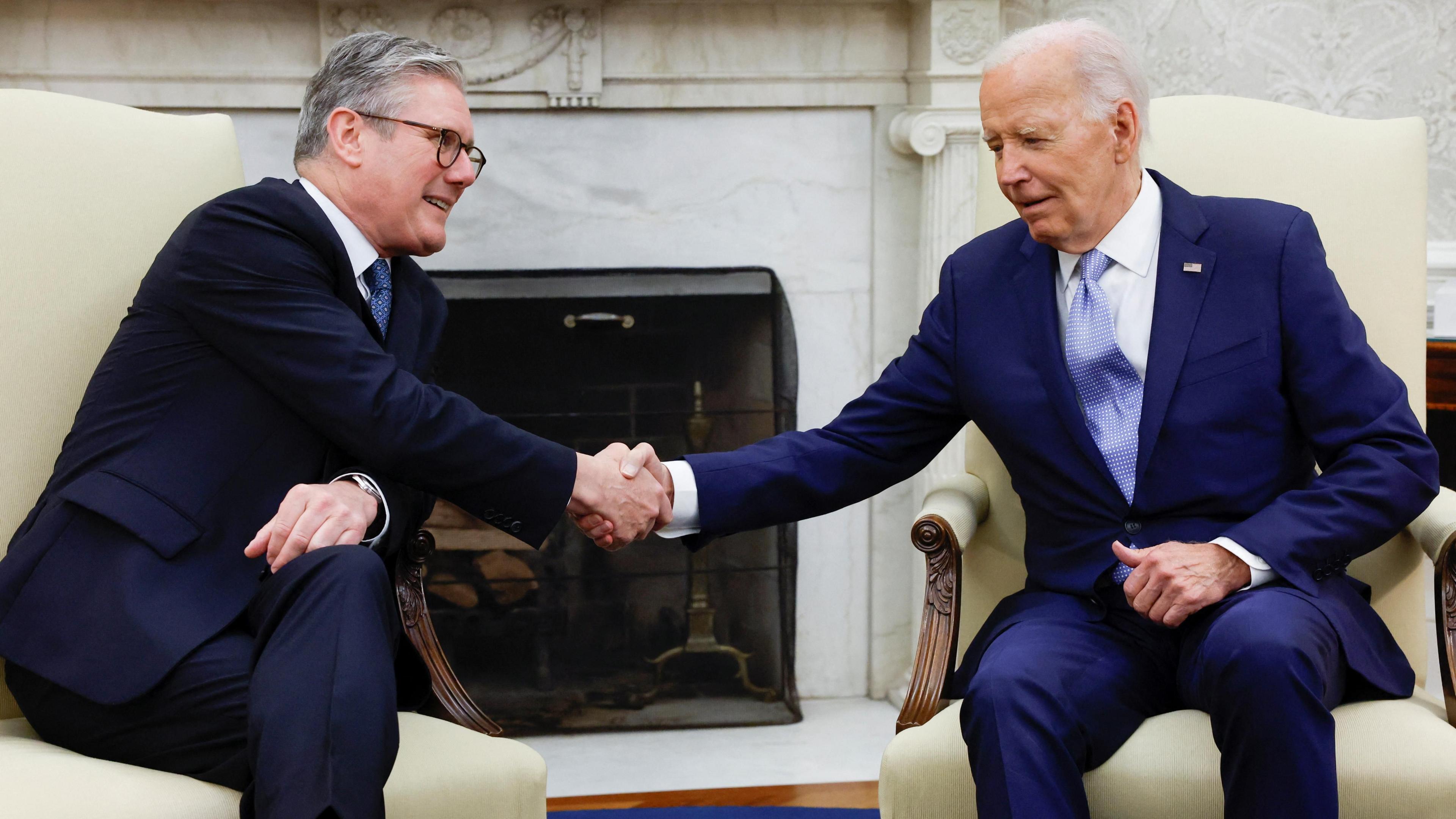

On the face of it, this past week’s Nato summit in Washington has ticked the boxes. The alliance can show it is bigger and stronger than ever, its military support for Ukraine appears undiminished and it has just sent a robust message to China to stop secretly supporting Russia’s war on Kyiv.

Sir Keir Starmer’s new government has had a chance to position itself as a linchpin in the transatlantic alliance at a time when political uncertainty hovers over the White House and much of Europe.

Back home in Britain, the priorities for this new government are pressing: the economy, housing, immigration, the NHS, to name but a few.

Yet unwanted threats and scenarios can often have a habit of turning up and upsetting the best laid plans.

So what could be coming down the track during the life of this new UK government?

War in Lebanon

No surprises here, this one is on everybody’s radar. But that does not make it any less dangerous, for Lebanon, Israel and the entire Middle East.

"The possibility of a large-scale Israeli invasion of Lebanon this summer should be at the top of the new government’s geopolitical risk register."

That’s according to Professor Malcolm Chalmers, the Deputy Director-General of the Whitehall think tank, the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI).

With the conflict continuing in Gaza and the Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping continuing, Prof Chalmers believes "we could be entering a period of sustained multi-front warfare in the region, for which neither Israel nor its Western partners will be prepared."

Ever since the Hamas-led raid into southern Israel on 7 October last year, there have been fears that Israel’s subsequent military campaign in Gaza could escalate across borders into a full-scale regional war.

Israel’s troubled northern border with Lebanon is where such a war is most at risk of igniting.

The daily exchange of fire across this border, between the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) and Hezbollah, the Iranian-backed Shia militia, have already resulted in hundreds killed, mostly in Lebanon.

More than 60,000 Israelis have been forced to abandon their homes and livelihoods in the north and an even greater number of people on the Lebanese side.

Domestic pressure is mounting for the Israeli government to "deal with" Hezbollah by pushing its forces north of Lebanon’s Litani River, from where they would have less chance of sending rockets into Israel.

"We don’t want to go to war," says Lt Col Nadav Shoshani of the IDF, "but I don’t think any country could accept 60,000 of its citizens displaced. The situation has to end. We would like it to be a diplomatic solution, but Israeli patience is wearing thin."

Rockets have been fired into Israel from Lebanon

There are strong reasons for both sides not to go to war.

Lebanon’s economy is already fragile. It has barely recovered from the 2006 war with Israel and a renewed full-scale conflict would have a devastating impact on the country’s infrastructure and its people.

Hezbollah, for its part, would likely respond to a major Israeli attack and invasion with a massive and sustained missile, drone and rocket barrage that could potentially overwhelm Israel’s Iron Dome air defences.

Nowhere in Israel is beyond its reach.

At this point, the US Navy, positioned offshore, could well join in on Israel’s side. Which then begs the question of what Iran would do.

It too has a sizeable arsenal of ballistic missiles as well as a network of proxy militias in Iraq, Yemen and Syria that could be mobilised to intensify their attacks on Israel.

One way to take the heat out of the tension on the Israel-Lebanon border would be for the conflict in Gaza to come to an end. But after nine months and a horrific death toll, a lasting peace has yet to be achieved.

Iran gets the Bomb

The Iran nuclear deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), designed to contain and monitor Iran’s nuclear programme, was the crowning foreign policy achievement of the Obama administration in 2015.

But it has long since fallen apart.

One year after President Trump unilaterally withdrew from it, Iran stopped abiding by its rules.

Buried deep beneath gigantic mountains, ostensibly beyond the reach of even the most powerful of bunker-busting bombs, Iran’s nuclear centrifuges have been spinning frantically, enriching uranium to well beyond the 20% needed for peaceful civil purposes. (A nuclear bomb requires highly enriched uranium.)

Officially, Iran insists its nuclear programme remains entirely peaceful, that it is purely for generating energy.

But Israeli and Western experts have voiced fears that Iran has a clandestine programme to reach what is known as "breakout capability": achieving a position where it has the capacity to build a nuclear bomb, but does not necessarily do so.

It will not have escaped Iran’s notice that North Korea, an isolated, global pariah, has been steadily amassing an arsenal of nuclear warheads and the means to deliver them, constituting a major deterrent to any would-be attacker.

If Iran gets the Bomb, then it is almost inevitable that Saudi Arabia, its regional rival, would also go after acquiring it. So would Turkey and so would Egypt.

And suddenly there is a nuclear arms race all across the Middle East.

Russia wins in Ukraine

Russia already occupies around 18 per cent of Ukraine

This depends on what you define as "winning".

At its maximalist, it means Russian forces overwhelming Ukraine’s defences and seizing the rest of the country including the capital Kyiv, replacing the pro-West government of President Volodymyr Zelensky with a puppet regime appointed by Moscow.

That, of course, was the original plan behind the full-scale Russian invasion of February 2022, a plan which failed spectacularly.

This scenario is currently thought unlikely.

But Russia does not need to conquer the whole of Ukraine to be able to declare some kind of "victory", something that it can present to its population to justify the astronomically high casualties it is sustaining in this war.

Russia already occupies around 18% of Ukraine and, in the east, its forces are slowly gaining ground.

Although more Western weapons are on their way, Ukraine is critically short of manpower. Its troops, fighting bravely, often heavily outnumbered and outgunned, are exhausted.

Russian commanders, who seem to care little for the lives of their men, have mass on their side. Russia’s entire economy has been placed on a war footing, with close to 40% of the state budget now devoted to defence.

President Vladimir Putin, whose recent "conditions for peace talks" equated to total capitulation by Ukraine, believes he has time on his side. He knows there is a high chance that his old friend Donald Trump will be back in the White House within months and that Western support for Ukraine will start to crumble.

Russia needs only to hang on to the territory it has already seized, and to deny Ukraine the chance of joining Nato and the EU, to declare a partial victory in the war it has portrayed as a fight for Russian survival.

China takes Taiwan

Again, there are plenty of warnings that this one might be coming.

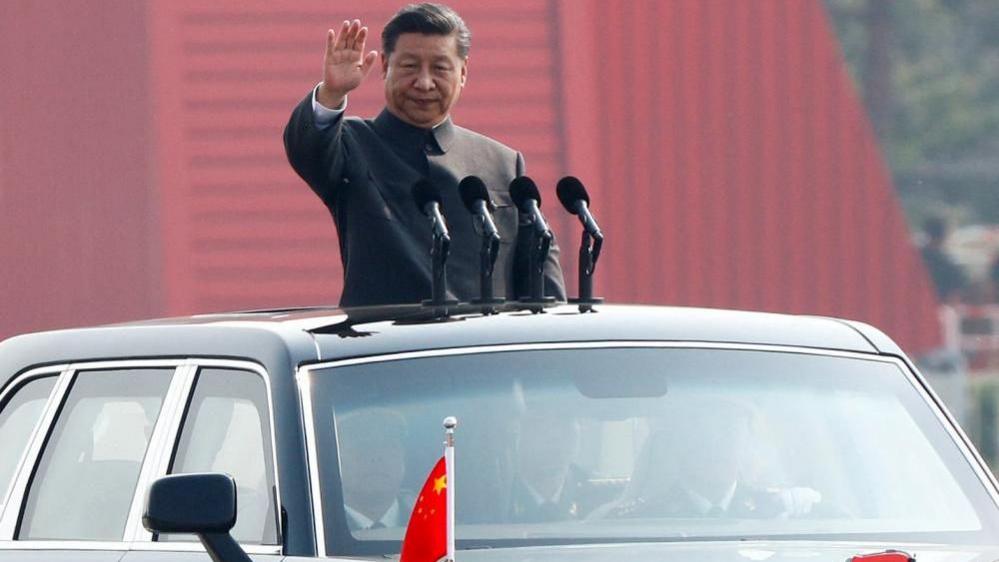

China’s President Xi Jinping and his officials have stated on numerous occasions that the self-governing island democracy of Taiwan must be "returned to the Motherland", by force if necessary.

Taiwan does not want to be ruled by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Beijing.

But China considers Taiwan a renegade province and it wants to see it "reunited" well before the centenary of the founding of the CCP in 2049.

The US has adopted a position of what it calls "strategic ambiguity" over Taiwan.

It is legally bound to help defend Taiwan, but Washington prefers to keep China guessing as to whether that means sending US forces to fight off a Chinese invasion.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has said repeatedly that Taiwan must be "returned to the Motherland"

China would almost certainly prefer not to invade Taiwan.

It would be hugely costly, in both blood and treasure. Ideally, Beijing would like Taiwan to give up on its dreams of full independence and volunteer to be ruled by the mainland.

But as that currently looks unlikely – the Taiwanese have watched with horror the crushing of democracy in Hong Kong – Beijing has another option up its sleeve.

If and when it decides to move on Taiwan, it is likely to try to seal it off from the outside world, making life unbearable for its citizens, but with the minimum of bloodshed so as to avoid provoking a war with the US.

Does Taiwan matter? It does.

This is about more than lofty principles of defending a democratic ally on the other side of the world.

Taiwan produces more than 90% of the world’s top-end microchips, the miniscule bits of tech that power almost everything that runs our modern-day lives.

A US-China war over Taiwan would have catastrophic consequences for the global economy that would dwarf the war in Ukraine.

Is there any good news?

Not exactly, but there are some moderating factors here.

For China, trade is all-important. Beijing’s ambitious plans to squeeze the US Navy out of the western Pacific and dominate the entire region may well be tempered by its reluctance to trigger damaging sanctions and a global trade war.

In Ukraine, President Putin may be making slow, incremental territorial gains but this comes at a horrendous cost in casualties.

When the Red Army occupied Afghanistan in the 1980s, it suffered around 15,000 killed over a decade, triggering protests at home and hastening the demise of the Soviet Union.

In Ukraine, in just one quarter of that time, Russia has suffered many multiples of that death toll. To date, protest has been limited - the Kremlin largely controls what news Russians see - but the longer this war goes on, the greater the risk that the Russian public will eventually baulk at the mounting number of their fellow citizens getting killed.

In Europe, where worries abound over a future Trump presidency withdrawing its historic protection, a new UK-led security pact is being prepared.

As the US presidential election in November draws closer, plans are accelerating to try to mitigate any possible downsides to the continent’s security.

Related topics

- Published12 July 2024

- Published11 July 2024