Metal mines pollution raises health worries

Toxic metals have polluted the river Ystwyth

- Published

More testing is needed in UK metal mine hotspots to see if there is a risk to public health, a leading expert says.

A Welsh Affairs Committee inquiry into the potential human health risks of pollution from abandoned metal mines in Wales takes place on Wednesday.

The north of Ceredigion is home to more than 400 of Wales’ 1,300 abandoned metal mines and its three rivers of the Ystwyth, Rheidol and the Clarach are some of the most heavily polluted in the UK.

The UK government said businesses must ensure the food they produce does not go beyond the maximum levels set by law.

A Welsh government spokesperson said it works with stakeholders to ascertain the nature and extent of metal mine pollution to identify ways to manage pollution.

Lead can cause IQ reduction in children and is a risk factor for heart attacks.

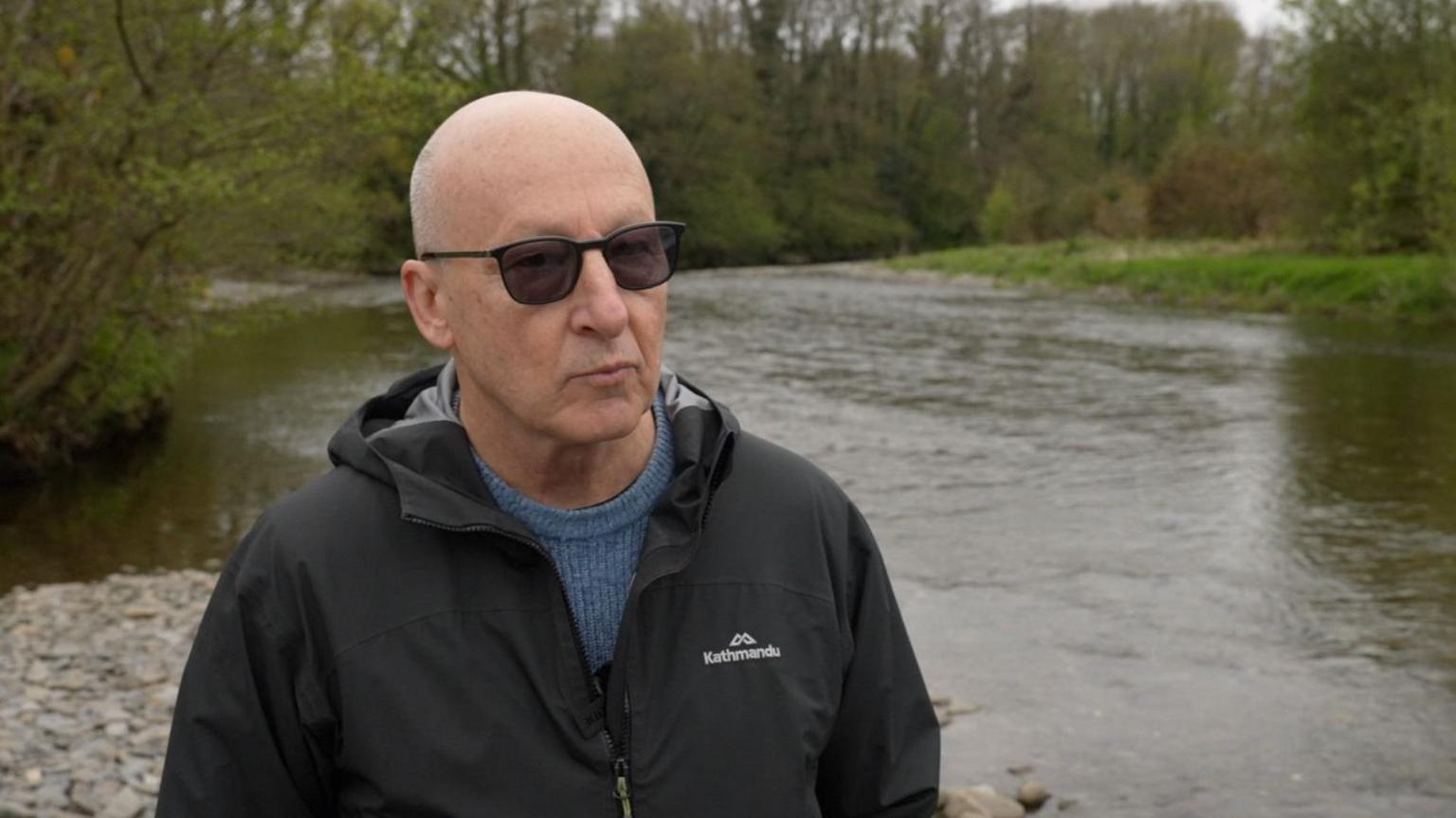

There is no safe level threshold for adults, says Bruce Lanphear, an expert on lead poisoning in children and adults.

There is no evidence of risk in Ceredigion, but this does not come as a surprise, he says, as low-level exposure is difficult to detect without testing or studies.

He warned that in mining communities in the United States, the waste from mines was often used in construction and warns that could pose a danger in the UK too.

“There could be a lot of contamination in and around housing, where chickens are kept, where kids play, and those are the kinds of exposures you’d worry about," he said.

Bruce Lanphear says low-level exposure is difficult to detect

To rule out any risks, potential threats need to be identified, Prof Lanphear said.

"One of the key functions of public health is to identify potential threats and to make sure if it is or isn’t real.

"If it’s not then people can be assured, and we can worry about other problems," he said.

That would then allow for additional steps to be taken if necessary, he added.

The UK government ruled out population testing in 2008.

Robin Morris and his wife have lived in Cwmystwyth, Ceredigion, for 45 years.

“Within sight of here and certainly within easy walking distance there are a dozen mine entrances where they used to work the mines," he said.

"You can see old spoil heaps, they’ve just been left, crushed the ore and left it just lying there."

The remnants of days gone by litter the hills above Robin Morris' home

The Cwmystwyth mines date back to the bronze age, and was finally abandoned in 1950.

Spoils from the remains at Cwmystwyth are extensive and include vast dumps across the landscape – spoils that include a high level of zinc, cadmium, and lead.

These toxic metals have polluted the river below.

Many locals have filtration systems installed if they receive their water from the hills where the old mines were once worked, others receive their liquid from elsewhere – a safety net against a potential health risk.

Toxic metals are polluting Welsh rivers

Dr Andrea Sartorius, a research fellow at the university of Nottingham said the UK was one of the biggest exporters of metals, especially lead, during various parts of the industrial revolution.

“The landscape is still affected by the actions of the past," she said.

Mr Morris lives in a hotspot for old metal mines in Ceredigion - one of several across the UK with others in north Yorkshire, in Cornwall, north East Wales.

The waters in Wales are of particular concern, with a recent Freedom of Information Act request revealing at least 500 tonnes of harmful metals leak into the Welsh environment each year.

Some of the soil also contains high lead concentrations

There is also a potential risk to agriculture and animals, with evidence of exposure.

A study by Dr Sartorius which looked at lead from abandoned mines in Wales specifically documented eggs containing levels of lead dangerous to children, if eaten once or twice a day, and enough to significantly increase an average adult’s exposure.

She also tested horses at another location 1km (0.6 miles) downstream which had died from a disease related to having high levels in their system.

The exposure may have come after drinking river water with high levels of lead in it in the river sediment. The soil in many of the pastures also contained high lead concentrations, she said.

Another study found that cattle had died after eating silage that was contaminated by the polluted flood waters.

Mark Macklin says climate change could increase flooding contamination

Mark Macklin, a lead author of that study, has also lived in the area for decades, and says that climate change could increase flooding contamination.

“The Ystwyth, the Rheidol and Clarach are very contaminated with legacy mining, but they’re not atypical and I think they represent potentially the tip of an iceberg," he said.

Natural Resources Wales said more frequent periods of extreme weather could potentially lead to increased erosion of contaminated material from abandoned mine sites and from historically contaminated sediments.

Its remedial strategies "take into account predicted rainfall and flow characteristics", it said.

Meanwhile farmers have to bear the brunt of the cost for testing their animals, which MP for Ceredigion Ben Lake says is not fair.

“The government should be leading the efforts and indeed the costs on this,” he said.

Ben Lake says farmers should not have to pay for testing their animals

The Welsh government said it provide a range of diagnostic, investigation, expert consultancy and advisory services to help farmers produce food that is safe to purchase and consume.

“Some of these are chargeable to farmers, and some - such as post mortem examinations and consequent laboratory testing - are heavily subsidised or free of charge to producers."

The UK government said: “An evidence review of the need for population screening was carried out by the UK National Screening Committee in 2018 which was not recommended because of concerns about testing and treatment and the lack of up to date population prevalence data."

It said enforcement action could be taken by local authorities if the maximum levels of lead in food were exceeded.