Night of terror remembered: 'All you could hear was screaming'

Maureen Mitchell was in the Mulberry Bush pub when the bomb exploded

- Published

This month it is 50 years since two bombs exploded in Birmingham pubs killing 21 people and injuring 220.

It was one of the worst atrocities of the Troubles, a conflict between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and Loyalists over a united and independent Ireland. The majority of bloodshed happened in Ireland and Northern Ireland but, by the early 1970s, the IRA had started a campaign of violence in England.

Those explosions in Birmingham ruined countless lives and continue to affect many to this day.

Three people who’ll never forget the events of that night are broadcasters Michael Buerk and Nick Owen who reported on the events, and Maureen Mitchell, then aged 21, who was in one of the pubs.

They spoke about their experiences for a new podcast for BBC Sounds, In Detail... The Pub Bombings. These extracts are taken from the series.

'We were on a war footing'

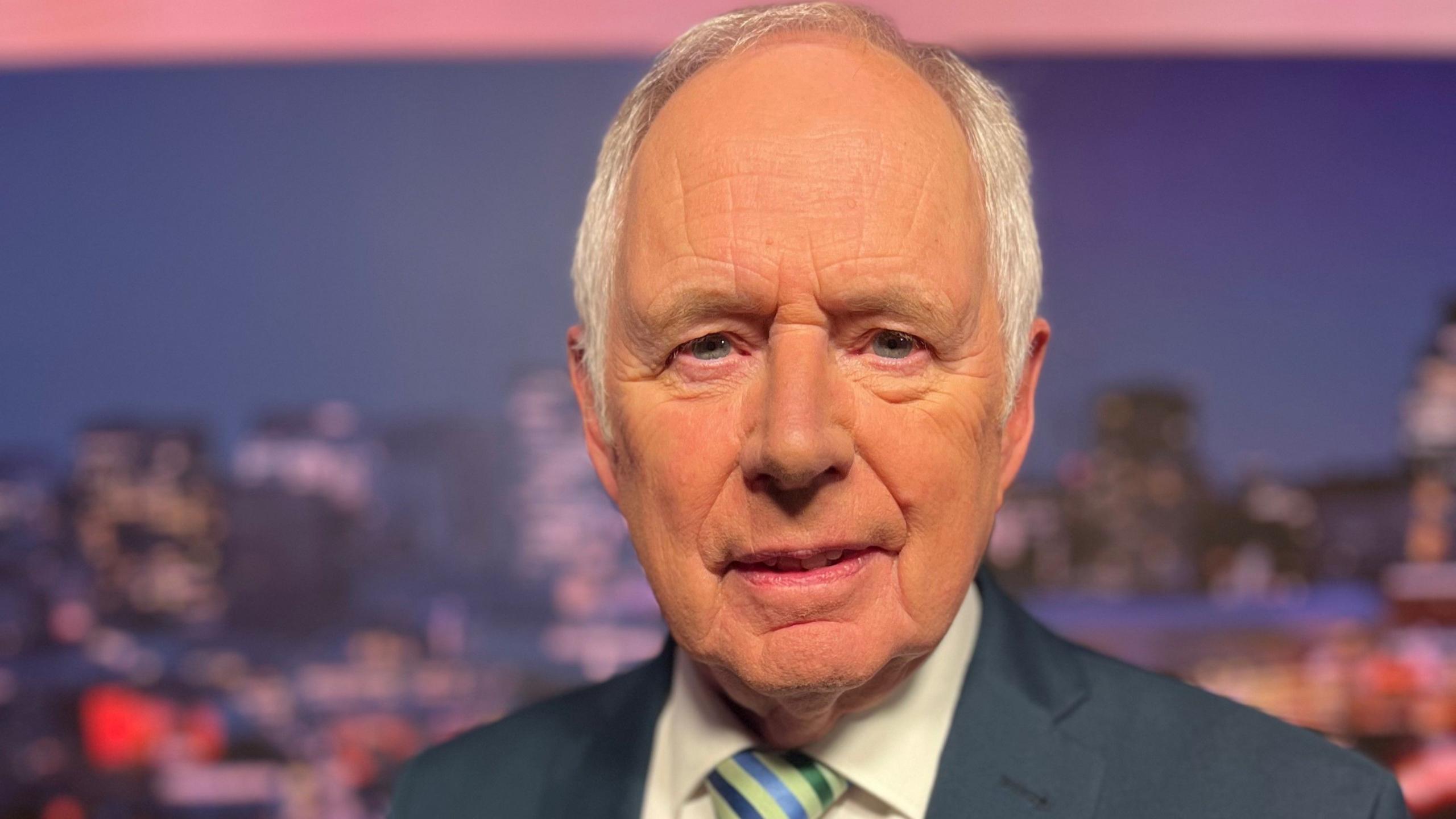

Nick Owen was a reporter for BBC Radio Birmingham at the time of the bombings

In 1974 Nick Owen was a reporter for BBC Radio Birmingham. On the day of the bombings, he’d been covering another major news story in the city. The previous week, IRA bomber James McDade had blown himself up planting a bomb in Coventry.

OWEN: James McDade's body was going to be flown back to Belfast and I remember hundreds and hundreds of police officers lining the route from Coventry all the way along the A45 to the airport.

Tensions were so heightened at that time that anything to do with an IRA person could be a target for a further outrage, and I think the police just wanted to make sure that his body got from A to B without any trouble whatsoever.

So his body was taken to Birmingham airport and I reported that at about 7pm – I think I did a report for Radio 4 as well as Radio Birmingham.

Things didn’t go to plan. Baggage handlers in Belfast were refusing to take the coffin so there were delays.

OWEN: I rang the newsroom of Radio Birmingham and the news editor said to me "you’d better come back, we think two bombs have gone off in pubs in town and there may be casualties".

We were on a war footing. The IRA basically had brought their war to the mainland because they were so desperate to get the British out of Northern Ireland, get the army out and so on.

There'd been this build up where everyone was nervous, anxious, feeling that sort of threat in the air.

But no-one, even for a minute, envisaged something quite so cataclysmic as that.

'You knew what had happened straight away'

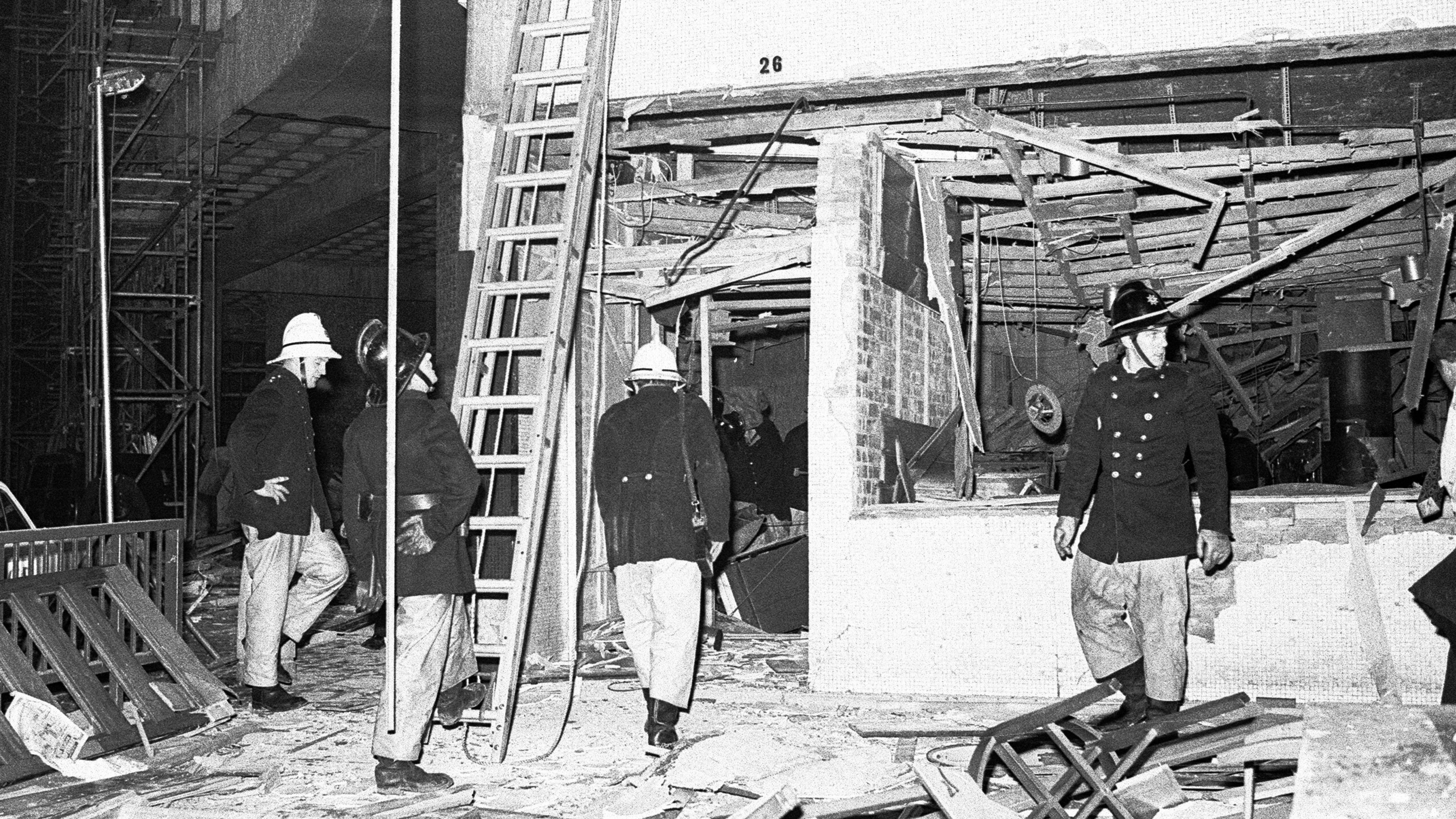

Two bombs were set off in pubs in Birmingham, killing 21 people

A warning call had been made to the offices of the Birmingham Post and Mail at 20:11 BST. Just minutes later the first bomb exploded in the Mulberry Bush pub, at the foot of the tall Rotunda building. Shortly after, another exploded in the Tavern in the Town, a basement bar on New Street.

Maureen Mitchell was with her fiancé, Ian, in the Mulberry Bush when the bomb went off.

MITCHELL: I don't remember the bang. It was just like a flash. And then it was just a feeling of floating through the air until you landed, and you knew what had happened straight away. You knew what it was. All you could hear was screaming.

Ian and a security guy carried me out, and they lay me by the wall, the wall's still there now by New Street Station. And I just kept saying “give me something for the pain”.

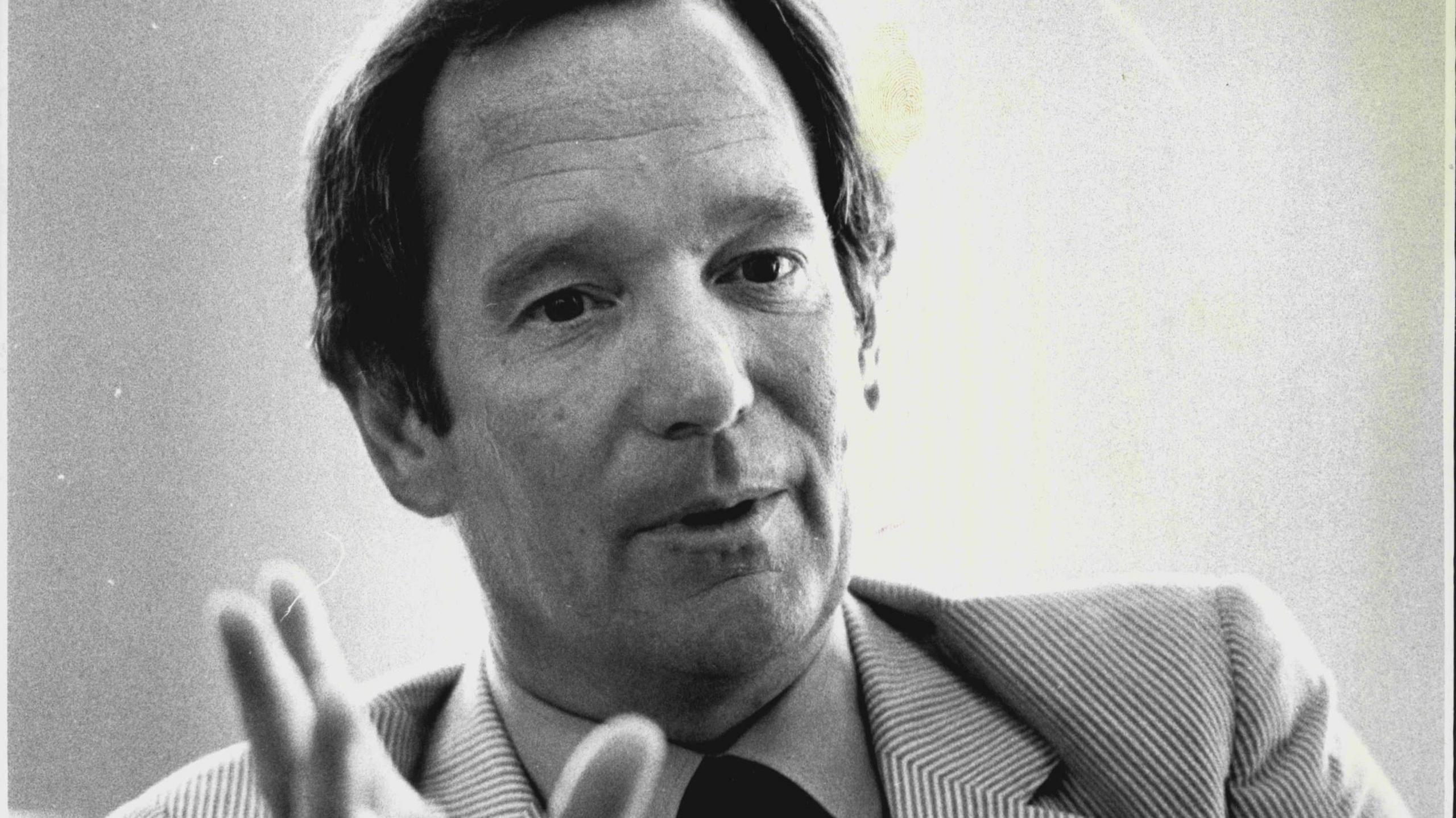

Michael Buerk was in the BBC newsroom in London when calls about the bombings started to come in

Michael Buerk was on duty at the BBC in London that night.

BUERK: Big stories have a momentum of their own. First of all, a phone on the news desk goes off and you suddenly see people running around, and then all the phones are going, and that was what happened that night.

I think within five or six minutes of the first call reaching the BBC newsroom, we were in the big, green, Vauxhall saloon crew car that we had in those days. And my memory is touching a hundred miles an hour going up the motorway.

In Birmingham, Nick Owen had by now made it back to his newsroom.

OWEN: People were shocked because stories were coming in that there were casualties, and a lot of them. At that stage it was just mayhem. A feeling of chaos because no-one knew what we were dealing with. We didn't realise the enormity immediately, but it soon became clear.

BUERK: I grew up on the outskirts of Birmingham. I did holiday jobs in New Street when they were finishing off [constructing] the Rotunda. I drank in the pubs around there, as a late teenager. This was home ground.

We got to the Mulberry Bush first. It had just been blasted into a great cavernous hole. There were body bags... there were people still running around. I have a distinct recollection of a man in a double-breasted blazer with lots of blood on him. He didn't seem to be severely injured, but [he was] crying outside the ruins of this place.

Michael Buerk reported from the hospitals the victims of the bombings were taken to

'Horrendous injuries'

MITCHELL: Outside the Mulberry Bush Ian asked this guy next to us, "have you got a cigarette, mate?" And this guy apparently said to him, "well, you can have one. But I don't know where you're going to put it". And he realised he's got a hole the size of an old half-crown in his cheek – he could put his tongue through his cheek.

OWEN: When I got to the Mulberry Bush the emergency services were sifting through the wreckage. I have memories of steam rising from the ruins. A friend of mine who worked on the Birmingham Evening Mail saw a finger in the rubble. Things like that will stick with you for a long time.

BUERK: It was that smell, I did a lot in Northern Ireland and subsequently elsewhere in the world. There's a smell you get after a big bomb, particularly in a crowded place. That smell of chemicals and charred flesh still hanging in the air.

OWEN: There were some horrendous injuries, pieces of furniture had gone through people's bodies.

People injured in the bombings were taken to three hospitals in the city

BUERK: Injured people were taken to three hospitals. I remember at the first hospital I went to one of the senior doctors said a lot of the seriously injured, and I imagine the dead too, were, as he put it, unrecognizable. He talked about how he tried to save some lad who'd had both his legs blown off, but he died of shock. He talked about the injured being burnt to a cinder, and the way he said it you knew this wasn't just a turn of speech.

MITCHELL: I had a piece of shrapnel going through my hip and lodged in my bowel. So I had part of my bowel taken away and it was like a hole. I felt “oh God, my stomach's going to fall out of me”.

That sounds crazy, but that's how it felt. And I just thought, “well I'm not going to get through this, I'm going to die, you know”. I was given the last rites the first night I was in hospital. It was that close, But they saved me. I was one of the lucky ones.

Maureen Mitchell suffered shrapnel injuries in the blast

'They'd got these men'

The police acted swiftly and within hours had detained six Irishmen. Five of them had taken a train from Birmingham New Street Station, shortly before the bombs exploded. They were travelling to Lancaster to catch a ferry to Belfast and were detained as they were boarding it.

It later became known that the men were returning to Belfast, in part to attend the funeral of the IRA bomber James McDade – some of them knew him. They were taken into custody and forensic tests showed that two of them had handled explosives.

The sixth man was arrested in Birmingham – he’d waved the others off at the station. Before long, four of the men had signed confessions admitting to the bombings.

BUERK: As I understand it there was a booking clerk at New Street Station who had been alerted in some way. Of course, the city was in a state of high tension anyway because of the IRA man, James McDade. And something or other about the men alerted the suspicions of this booking clerk.

OWEN: I think the whole of Birmingham, and I know I did, felt relief and, not quite joy because it's such a dismal topic, but pleasure that the police had acted quickly. They'd got these men, and they were going to serve the rest of their time in prison for the horrors they inflicted.

MITCHELL: I remember my brother coming to see me at the general hospital which was opposite the police station. And I remember my brother saying to me “I just want to walk in that police station and just kill them”.

Emergency services had to sift through the wreckage

'We all felt very angry'

In June 1975 the six men went on trial, each charged with 21 counts of murder. Michael Buerk covered the trial for the BBC.

BUERK: The trial was held in Lancaster Castle and it would be difficult to think of a more secure place to have one. The walls were 10-foot thick, the security was absolutely extraordinary. There were a hundred police, a lot of them armed, and dogs. I had to go through six separate checkpoints.

I've covered a lot of trials of one sort or another, and I've never seen security like that. Within these 10-foot thick walls, there was a specially constructed dock and I remember the six of them looking like pretty bedraggled, diminished figures.

The case rested on three pillars. First was their alleged sympathies for the IRA. They were, after all, on their way to the funeral of an IRA man who'd blown himself up with his own bomb.

The second was the forensic evidence. The prosecution expert eventually nailed his colours to the mast and said that he was 99% certain that two of the six had been handling explosives.

And the third was their confessions. They confessed to this, the worst, at that time, crime in British criminal history in which 21 people had died.

After 45 days in the dock, the men were each handed 21 life sentences.

OWEN: I know it's a cliche, but it was closure. Particularly for the victims, their families and so on but for all of us - because we were all in this together. We all felt very strongly, were very angry about the whole thing.

Michael Buerk covered the trial of the Birmingham Six for the BBC

Michael Buerk produced a report for the BBC’s nine o’clock news that night.

BUERK: I watched it from a rather expensive hotel room in Manchester with a room service dinner and a bottle of champagne. And I felt extraordinarily pleased with myself.

But, I thought subsequently, there I was, quaffing champagne and having a deluge of praise in a smart hotel in Manchester. Whereas the Birmingham Six were on their way to a grim, as it turned out, 16 and a half years.

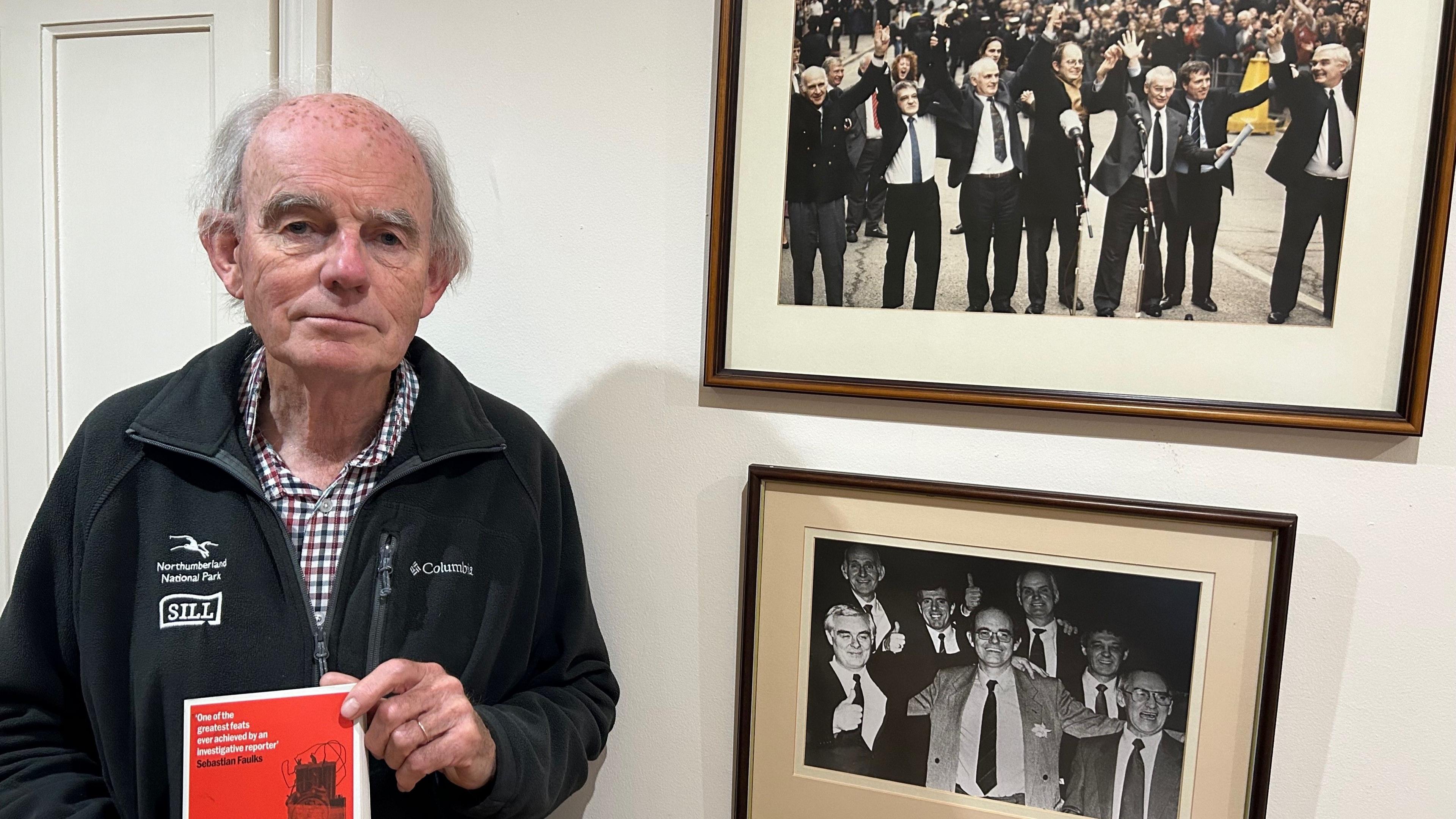

Labour MP Chris Mullin campaigned on behalf of the Birmingham Six

Throughout the eighties, doubts began to surface about the convictions, thanks largely to the work of investigative journalist and Labour MP Chris Mullin, who set out to prove that the wrong men had been locked up. The Birmingham Six were eventually freed on appeal in 1991 after it emerged that the evidence presented to the court was deemed ‘unsafe’ and that their confessions had been forced out of them.

BUERK: I don't think those of us in the court had any doubts at the time. We were all convinced they were bang to rights. [After their release] I thought how stupid I'd been not to be a little bit more wary at the time.

I blame myself a bit for not seeing some of the inconsistencies that might have been fairly obvious. How the confessions, for instance, seemed to vary. But what would I have done if I had? I found it difficult, I suppose because I was so horrified by what I'd seen and what I'd heard talked about on the night itself.

I was keen to have my feelings of antagonism to whoever had done it pinned on palpable human beings and, for a while, I was a bit reluctant to engage with the idea that they might not have been guilty. So it took me some time to come round to that.

MITCHELL: I can't remember how I heard they were being released, but we went home from work and there was just reporters all around the front door. I was just in bits. It was devastating. If they didn't do it, who did? I was convinced that somebody was paying for what had happened, to have that taken away from me, just knocked me straight off my feet.

Throughout the eighties doubts began to surface about the guilt of the Birmingham Six

To this day, no-one has been rightfully brought to justice for the Birmingham Pub Bombings and campaigners are calling for a public inquiry.

You can hear more about this in the new series from BBC Sounds, In Detail: The Pub Bombings.

OWEN: It seems incredible to me that 50 years after it happened, we're still talking about the Birmingham pub bombings. Something that happened when I was early in my broadcasting career. Every time there's a new development you think perhaps we're getting somewhere. And then at the end of it, you feel perhaps we aren't. I just really feel for the campaigners – they must go through such agonies. It's dominated their lives since 1974.

MITCHELL: I think the stories I've heard, people that were there, but not badly injured, were affected more psychologically than people like me were. And somebody said to me, that's because I was in hospital and so I had a lot, a lot of attention.

I did meet with one man who said he was he wasn't that injured, he walked out, he didn't even go to hospital. He said he went home, he never told his wife that he was actually there. In all the years after, he never told his wife how he felt. Another lady got in touch who said she and her husband, were actually just walking past [one of the pubs].

And she said he was such a gentleman, such a quiet man, but she said he started drinking and it totally changed him.

BUERK: It still sticks in my craw that nobody has faced justice for doing the most appalling thing that I can imagine anybody ever doing.

OWEN: As someone who was there at the time, I would like to know. I would like some sort of closure from a journalistic point of view. I think it'd be really good to know and to see the faces of the people who actually did it, if they're still alive.

These extracts were taken from interviews given to the new BBC podcast ‘The Pub Bombings’, available here.