Scottish drug deaths fall but remain worst in Europe

The number of drug deaths fell last year

- Published

Scotland remains the drugs death capital of Europe for the seventh year in a row despite a 13% fall in fatalities, official figures suggest.

There were 1,017 drug misuse deaths in 2024, external, down 155 from the previous year.

National Records of Scotland said the latest figure was the lowest annual number since 2017. It brings the total in a decade to 10,884.

After adjusting for age, there were 191 drug misuse deaths per million people in Scotland in 2024.

According to the most recent European data, the next highest rate was Estonia with 135 deaths per million in 2023.

Scottish Drugs Minister Maree Todd said the fall in deaths was welcome but that there was "still work to be done".

Experts say they are concerned about the potential for deaths to increase again this year.

Kirsten Horsburgh, chief executive of the Scottish Drugs Forum said the recent arrival of deadly synthetic opioids known as nitazenes was "a crisis on top of a crisis."

Suspected deaths early in 2025 "are already higher than they were last year, external" she said.

How did we get here?

This is a crisis with deep roots in the social and economic changes which swept through Scotland in the latter half of the 20th Century as the country's economy shifted away from manufacturing.

When the shipyards, steel mills and collieries fell silent, they left a generation of men, whose pride and identity had been bound up with the things they made, struggling to adapt.

Society changed rapidly too. The old city slums were cleared, but many people were moved to damp, isolated tower blocks with limited amenities.

It was a recipe for joblessness, family breakdown and addiction.

In 1972, in a famous speech at the University of Glasgow, the trade unionist Jimmy Reid said Britain's "major social problem" could be summed up in one word - alienation.

Men, he said, viewed themselves as "victims of blind economic forces beyond their control" leading to a "feeling of despair and hopelessness that pervades people who feel with justification that they have no real say in shaping or determining their own destinies."

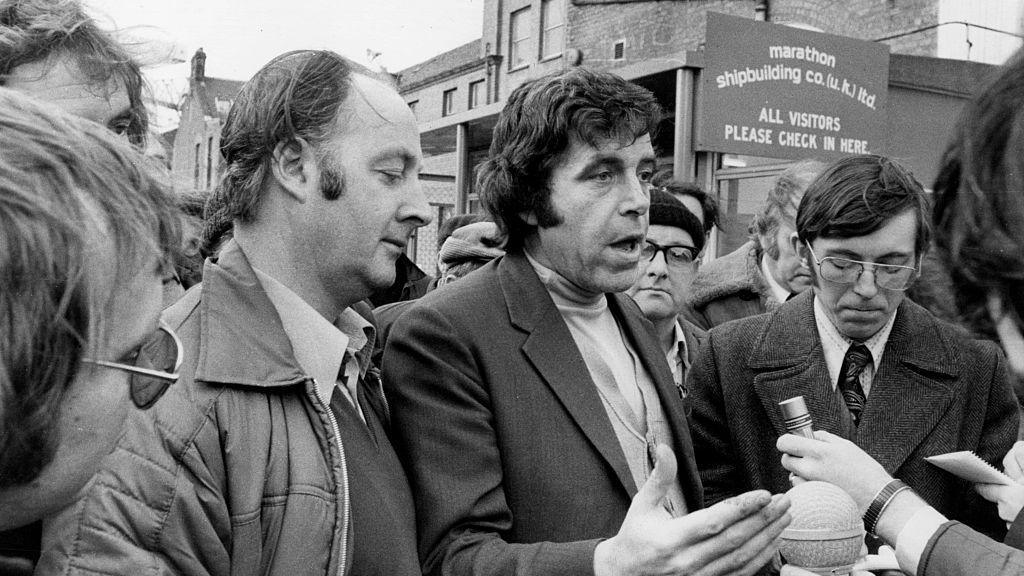

Trade unionist Jimmy Reid speaks to the press at the Marathon oil rig yard in Clydebank in 1976

One way alienation found expression, said Reid, was in "those who seek to escape permanently from the reality of society through intoxicants and narcotics."

Half a century after his speech, Scotland is still grappling with alienation and still struggling with the scourge of alcohol and drugs.

High unemployment in the 1980s was followed by cuts to public spending after the financial crash of 2007/8 and the skyrocketing cost of living this decade.

By 2024, people in the most deprived parts of Scotland were 12 times more likely to die from drug misuse than those in the richest areas.

For many years this was a particularly male problem.

In the early 2000s, men were up to five times more likely to die of an overdose than women although that gap has since narrowed to twice as likely.

As demand for drugs rose, so did supply. From 1980, heroin from Afghanistan and Iran began to arrive in Scotland, external in large quantities, with deadly results.

The sharing of dirty needles by injecting drug users and the arrival of HIV led to a public health crisis which was graphically depicted in Irvine Welsh's 1993 novel, Trainspotting, and its film adaptation.

That crisis evolved in the decades that followed as it became more common to use cocktails of drugs. In 2024 four in five drug deaths involved at least two substances.

'Drugs are becoming normalised'

Drug overdoses are not the only evidence that Scotland is experiencing a crisis related to alienation. Other so-called deaths of despair are also high.

Scotland has a higher rate of suicide than other parts of the UK and some of the highest levels of alcohol-related deaths in Europe.

These too are often linked to poverty. In 2023, deaths directly caused by alcohol were 4.5 times higher in the most deprived areas of Scotland than in the least deprived.

Taken together, says Annemarie Ward, of the charity Faces and Voices of Recovery UK, Scotland has a "penchant for oblivion".

Annemarie Ward said taking illegal drugs was becoming normalised

Illegal drugs, she argues, have become part of the national culture.

"It's become normalised," she said. "I don't think we have to accept that normality."

Of course, deprivation and despair are not unique to Scotland and do not on their own amount to a sufficient explanation for its crisis.

Various other theories have been put forward including the existence of a macho, hard-partying culture; a reluctance, especially among men, to seek mental health support; and even the country's long, dark winters.

Another suggestion is that years of substance abuse are now catching up with the ageing Trainspotting generation - although this is disputed.

Since 2000, the average age of a drug misuse death has increased from 32 to 45.

Another potential explanation is the ripple effect of trauma.

When more than 1,000 people are dying every year in a small country, the implications for their families and friends are enormous and potentially catastrophic.

Drugs have scarred whole communities with abuse of substances continuing from generation to generation.

Dr Susanna Galea-Singer said people seeking treatment for drug addiction have often experienced trauma

Nearly "every person who seeks treatment has been traumatised in some way," says Dr Susanna Galea-Singer, chair of the Faculty of Addictions at the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland.

Last year, Public Health Scotland published a review of all drug deaths in 2020, external which revealed that 602 children lost a parent or parental figure to overdose in that year alone.

"You get social fragmentation when you have aspects of poverty, aspects of trauma," said Dr Galea-Singer.

"You burn bridges with families, it's just extremely difficult. It does fragment society."

Trauma might explain a high or even rising level of drug deaths but even it does not adequately account for a dramatic jump in the numbers a decade ago.

There appear to be two main reasons for the surge in deaths at that point.

First, in 2015, the Scottish government cut funding for alcohol and drug partnerships, external, which co-ordinated local addiction services around the country.

Kirsten Horsburgh, CEO of the Scottish Drugs Forum, warned of the deadly impact of synthetic opioids

"We saw the start of a really sharp increase in drug-related deaths," said Kirsten Horsburgh of the Scottish Drugs Forum.

"There's no doubt that cuts to funding in this area reduces the amounts of services that people can access, reduces the staff that are able to support people and results in deaths."

Ministers later boosted resources as part of a five-year "national mission" to tackle the drugs emergency, only for funding to fall again in real terms in the past two years.

The 2015 cuts were "a disaster," said Ms Horsburgh. "Even with increased resource as part of the national mission, we can see it's still not enough.

"We can't just have small pilots of projects to address a public health emergency.

"We would not do that for any other public health emergency. We did not do that for Covid. We should not be doing that for the drug deaths crisis."

The second big change came around the same time as drug services were being cut.

It was the arrival on Scottish streets of dangerous benzodiazepenes known as street valium.

Street drugs being sold as valium have been blamed for causing more drug-related deaths

These blue pills were a fake and powerful version of the anti-anxiety medication, Valium, and they were deadly.

Nicola Sturgeon, who was first minister at the time, would later admit that her SNP government had taken its "eye off the ball" as deaths rose.

How to tackle the issue now remains contentious.

Many public health experts support a harm reduction approach involving the provision of substitute drugs such as methadone, clean needles, and a drug consumption room which has been set up in Glasgow.

"Harm reduction has to be the core of any effective evidence-based drugs policy approach," said Ms Horsburgh of the Scottish Drugs Forum.

She is among those calling for decriminalisation of all drugs while others argue for a transfer of related powers from Westminster to Holyrood.

Harm reduction

Annemarie Ward of Faces and Voices of Recovery UK agreed that harm reduction should be part of the mix but said the balance needed to tilt towards rehabilitation.

"When government ministers talk about treatment in Scotland, what they're talking about is harm reduction," she said.

"When the general public hears the word treatment, they're thinking detox, rehab, people getting on with their lives."

Ms Ward also wants a shift away from NHS provision of drugs services in favour of third sector provision of rehabilitation and recovery.

Her charity advocates for such solutions but does not provide them directly and does not receive government funding.

"Our treatment system is delivered through the public sector, which means it's incredibly bureaucratic. So you can't just walk into a service and get seen that day, for instance, the way you can in England."

Ms Horsburgh and Ms Ward may have different priorities for tackling the crisis but both agree that it is almost certainly about to get worse.

"Nitazenes are a whole new ball game," warns Ms Ward.

"These are the synthetic opioids that are 100 times stronger than your average hit of heroin, and they're also ending up in the coke supply."

Cocaine deaths in Scotland reached a record high of 479 in 2023 and remained at exactly the same level in 2024.

Nitazenes are not sought out by users but are used by dealers to adulterate other drugs.

They were implicated in 76 deaths in 2024, three times as high as in 2023.

But Ms Ward predicts an exponential rise this year "unless we start to help people get clean and sober again."

If she is right, Scotland has not yet got to grips with this emergency despite this year's fall.

The causes of the drug deaths crisis are multiple and complex.

But the fear is that they are producing a cumulative and compounding effect from which it is proving almost impossible to escape.

Related topics

- Published24 November 2021

- Published27 August

- Published30 July