Tan lines. Once hidden, now sought after, but can they make a safe comeback?

- Published

"I am literally going to apply this fake tan all over my bikini top," Jemma Violet says, as she smears chocolate brown mousse over her chest, neck and halter-neck bikini.

I'm watching a TikTok video in which the beauty influencer is explaining how to develop a vibrant set of tan lines - without sunbathing.

"Make sure you do your arms and everything... and then wait a couple of hours before washing it off."

A flash frame later and Jemma is showing off two very visible white stripes connected to two white triangles poking out of the top of her boob tube. Tan lines glowing, job done.

Back in the 90s, I remember the abject horror of having tan lines on display and doing all I could to even mine out - with limited success. Fast forward to the mid 2020s and tan lines have become a fashion statement to be shown off.

"When they were out of style they were seen as an imperfection, now they're associated with the summer and an active lifestyle - they've become desirable," Jemma says.

"This year it's risen to a whole other level - they're even on the catwalk."

Some fake tanners are even using masking tape - the type I use on my skirting boards - to create that crisp line across their skin.

"My videos are about getting that tan line safely," Jemma says. "I feel pretty captivating, the look is eye-catching - especially the contrast between the darker skin and the white tan lines."

Jemma is one of thousands extolling the virtues of tan lines, with posts notching up more than 200m views on TikTok.

But alongside fake tanners like Jemma, there are just as many heading outdoors and under the hot sun, determined to create real tan lines - even if that means burning themselves and suffering the painful consequences.

Hashtags such as #sunburntanlines, #sunpoisoning and #sunstroke are popping up alongside videos of young men and women - some in tears - revealing deep red, almost purple, often puckered skin. Some are asking for help and advice, others actually want to show off their badly sunburned bodies. I've even seen one young woman proudly stating, "No pain no gain".

Sunbathers by a hotel swimming pool in Italy, 1974

Having a visible tan in Victorian times was a clear sign you were poor working class and probably spent most of your time hawking barrels of hay for very little recompense.

By the 1920s, a few freckles and a well-placed tan line would probably mean you had moved up a social class or two, and suggested health, wealth and luxurious holidays.

By the 1960s and 70s sun lovers were using cooking oil and reflective blankets to deepen their tans. But the links between ultraviolet (UV) radiation and skin cancer were becoming more widely known - and indisputable.

So marked the beginning of a complex relationship with the desire to change our skin colour - and while tans are still sought after by millions of us, there is now little doubt a natural one carries with it a hefty element of risk.

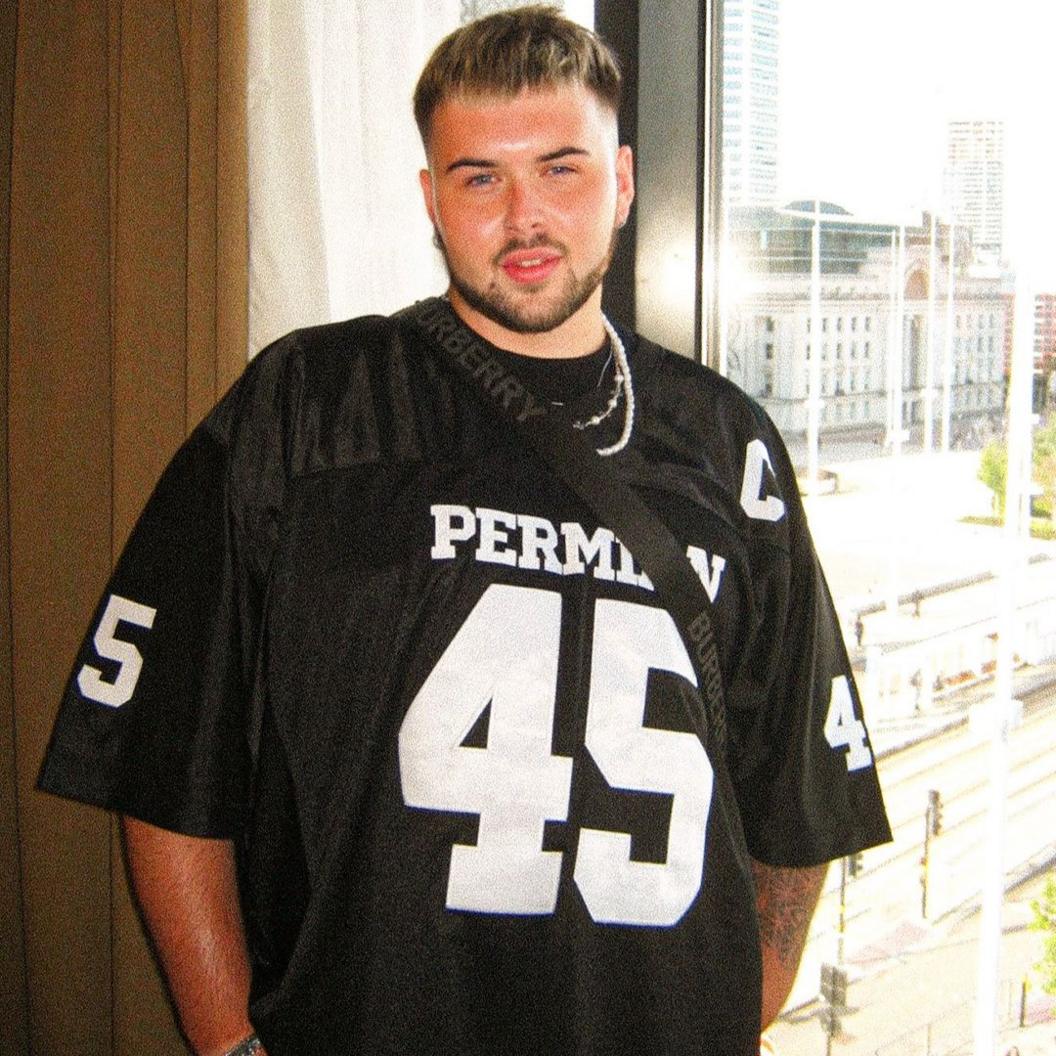

Jak Howells

If someone had lectured Jak Howells about the risks of sunburn a few years ago those warnings would likely have fallen on deaf - and probably sunburnt - ears.

"I know it seems strange to be addicted to lying on a sunbed," the 26-year-old from Swansea says, "but I was."

It began when Jak was 15, with a few of his older mates in school using them. By the time he was 19 Jak was on sunbeds five times a week, for 18-20 minutes at a time.

"My skin was so burned - my face looked like a beetroot. But I kept on going back for more," he says. "I knew in the back of my mind that there was a risk - I wasn't oblivious - but I didn't take it seriously.

Jak says he used to enjoy when people complimented him on how he looked and remarked on his tan.

"It gave me such a buzz, I loved it," he says.

But it was seeing the look of horror on his mum's face, as she examined a bleeding mole on his back, that made Jak realise his love of sunbeds had gone too far.

Jak Howells's melanoma

Just before Christmas 2021, Jak was diagnosed with melanoma, external, one of the most dangerous types of skin cancer, which can spread to other parts of the body.

What followed, he says, were two years of "hell and horror". Jak had a complicated operation that involved surgeons cutting away two inches of skin from his lower back, chest and groin. But three months later the cancer was back.

Jak then had immunotherapy - which uses the body's own immune system to fight the cancer - and was told if that didn't work, he had only a year to live.

"The sickness was horrific - I would lie in bed for days," Jak says. "It felt like I had been hit by a bus. I had such a damaged body, I was a shell of a human. I lived for the next scan, the next treatment."

'Massive backwards step'

Melanoma skin cancer rates in the UK have increased by almost a third over the past decade. I asked Megan Winter from Cancer Research UK why this is happening in an era where the risks posed by harmful rays from the sun and the links to skin cancer are now well known.

"It's partly down to those people who may have burnt several decades ago," she explains. "You only need to get sunburnt once every two years to triple your risk of getting skin cancer."

As a population, we are growing older, so are "more likely to see more cancers" and "we are spotting them more quickly", she adds.

However, there are also concerns part of the increase could be down to the volume of misinformation doing the rounds online.

"We've taken a massive backwards step," says Dr Kate McCann, a preventative health specialist. "The message that the sun is good and sunscreen causes cancer is a complete loss of health literacy."

Fake sunburn featured at London Fashion Week

She says the current trend to create tan lines by burning in the sun, coupled with false claims that suntan lotion is responsible for the very cancer it's trying to prevent is a "perfect storm".

"If I see a child or a young person with sunburn now, I know they have an increased risk of cancer in 20 or 30 years."

While there are some ingredients in suntan lotions - like oxybenzone - that can cause environmental damage to coral reefs, there is not evidence to suggest it poses a risk to humans, Dr McCann says.

"If you don't want to use a suntan lotion with certain chemicals there are plenty of more natural ones on the market - zinc and mineral based ones - but you can't just stop wearing sunscreen."

Jak Howells following his treatment

As a young man Jak relished his tan lines. Now he says he's frightened by the sun and lathers himself up in SPF before even thinking about stepping outdoors.

Given the all clear from cancer in December 2022, he now has a career he loves making content and talking about his experiences to raise awareness.

Looking back he says he realises what happened to him was "probably self inflicted".

"For a long time I blamed myself and I beat myself up about it," he says. "But I have been lucky enough to live through the consequences - and they were horrendous. So maybe now I feel like I've done my time."

Back on TikTok, in her own way, beauty influencer and fake tanner Jemma is also trying to prevent others from going through what Jak did.

"Skin damage is real," she says. "We're not doing that."

A list of organisations in the UK offering support and information with some of the issues in this story is available at BBC Action Line

Related topics

More weekend picks

- Published22 June