Greece warns of 'invasion' as it halts asylum on Med route

People arriving from North Africa are held in Crete before being moved to the Greek mainland

- Published

In the centre of a sweltering, cavernous hall, rows of men sit in silence with nothing to occupy them but the wait.

Signs from an old tourist fair propped up behind them urge visitors to "Explore the Beauty of Nature" with illustrations of coves and beaches in Crete.

But those held in the former Ayia exhibition centre did not come to the Greek island as holidaymakers. They are migrants who risked a journey across the sea from Libya to Europe's southern tip and were then detained and denied the right to apply for asylum.

From Crete, they are now being moved to closed facilities on the mainland.

The right for anyone to request protection, or asylum, is inscribed in EU and international law and in the constitution of Greece itself. But in a move implemented in haste earlier this month and criticised by human rights lawyers, the government has over-ridden that principle for the next three months at least.

The new migration minister, Thanos Plevris, has told the BBC his country faces a "state of emergency". He warns of an "invasion" if Europe does not enact tough measures and talks of the need for strong deterrence.

"Anyone who comes will be detained and returned," he stresses.

Now even people fleeing war in Sudan are locked up with no chance to explain their story.

Crete is now in the middle of tourist season and protecting its reputation is a priority for the government

Inside the old exhibition centre, migrants were warned off speaking to us by the guards. "They're in detention," we were told.

Greece is baking in a heatwave and many of the men were in vests or stripped to the waist. There were a few water taps around the edges but no proper showers and only grubby blankets on the floor. Boxes of donated clothes and toys piled up by the door remained unpacked by guards wary of provoking fights.

Over two days we saw just a couple of hundred migrants at Ayia – from countries including Egypt, Bangladesh and Yemen, we heard, as well as Sudan.

There were 20 or so teenage boys and two women sitting together at the back.

But when 900 people landed from Libya during one weekend earlier this month, the facility was stretched to the limit.

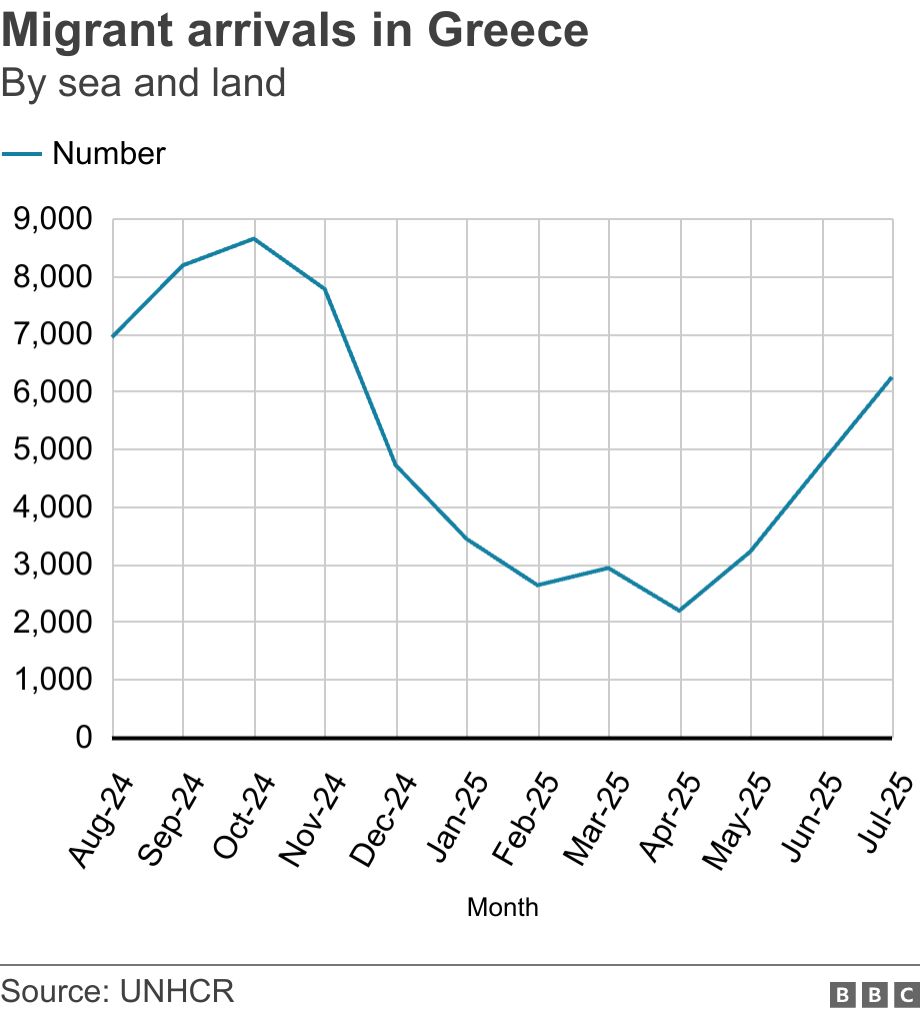

More than 7,000 migrants reached Crete between January and late June, more than three times the number in 2024.

In all, the EU's Frontex border agency recorded almost 20,000 crossings in the Eastern Mediterranean in that period, with the Libya-Crete corridor now the main route.

Traffickers began sending people to Crete in earnest after Italy signed a deeply controversial deal with Libya a couple of years ago that allows for migrants to be intercepted at sea and pushed back despite extensive evidence of human rights abuses.

It was mid-July when the government in Athens made its own move.

"The road to Greece is closing," Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis told parliament, announcing that all migrants "entering illegally" would be arrested.

A few days later, Mustafa – a 20-year old who ran from the war in Sudan – was detained.

From Ayia he was transferred to a camp outside Athens known as Amygdaleza, rows of grey prefabricated huts in a parched clearing surrounded by tall fences and security cameras.

"We are living here like a prison," Mustafa told me, when I managed to make contact by phone. "They don't allow us to move. We don't have clothes or shoes. Our situation is very bad."

Lawyers who have visited Amygdaleza confirm his account, describing recent arrivals walking barefoot on baking hot soil and receiving minimal information. Ordinarily, Sudanese citizens would be granted asylum in Europe.

Migrants detained in Crete are eventually moved to this camp outside Athens

In a series of voice and text messages, Mustafa recounted how he had spent months in dire conditions in Libya waiting for his chance to cross. He was then at sea for two days with 38 people crammed on to a plastic boat that had to be rescued. "We didn't manage to reach [land] because of the waves."

Having survived that ordeal, he is now scared Greece will try to return him.

"I left my country because of the war, I can't go back," Mustafa said. "I come from Sudan because there is war in Sudan and I want protection. That's why I came here."

"Now we do not know what our fate will be."

Greek migration minister Thanos Plevris says the suspension of asylum rights will last for three months

The Greek migration minister describes himself as "hardline" on immigration.

"It's clear a country cannot accept such pressure from migration and not react," Thanos Plevris defended the government's new measures.

He claimed that Crete had been receiving "one, two, three thousand people a day" from Libya when it stepped in, though he then scaled that back to "close to a thousand" in three days, when challenged.

Plevris has no qualms about withholding the right to request asylum, suggesting that Sudanese refugees could simply stay in Libya.

"I want to be completely honest. We try to strike a balance between respect for their rights and respects for the people in Greece," the minister was firm. "Anyone who enters Greek territory over the next three months knows they are violating Greek law."

The European Commission says it's "looking into" the move.

A spokesperson told the BBC the situation was "an exception" because the surge in small boat arrivals had "possible consequences in terms of European security".

Poland also halted asylum applications on its eastern border back in March, though with various exceptions. Greece itself did so previously in 2020 during an increase in arrivals from Turkey.

Certain obligations of the European Convention on Human Rights can be overridden "in time of war or other public emergency threatening the life of the nation".

Whether the current situation constitutes such a grave threat to either Poland or Greece is much disputed.

"This article is for war or a massive uprising," argues Dimitris Fourakis, a lawyer who works extensively with migrants in Crete and sees a troubling trend across Europe.

He warns that detention centres will quickly fill up, too, as "sending migrants back" is easy to say but extremely difficult to do.

"I think it's a decision that is completely illegal. It's a very big step, very wrong step. And I think the best they can is to stop it immediately," the lawyer says.

The increase in small boat arrivals came just as the beaches and bars of Crete were filling up for the summer and the migration minister says protecting the tourist industry is his priority.

"I've never seen any migrants," admits Andreas Lougiakis, a restaurant owner in the pretty village of Paleochora on the southern coast who says the boats mostly reach the tiny island of Gavdos.

Even talk of their arrival is bad for business though.

"We feel sad for these people of course, but… people think this place is full of immigrants; no beaches available, no place," Andreas says. "We are just worried for our business and for our families."

The suspension of asylum is part of a much broader crackdown on irregular migrants here. The minister plans to jail all those who fail to leave Greece when their asylum request is rejected and use electronic tags for surveillance.

He has also promised a "drastic review" of benefits.

Claiming that "millions" in North Africa are poised to cross to Europe, citing conversations in Libya, Plevris suggests other countries should be grateful for his resolve.

"You should know that if the countries on the border of the EU do not take tough measures, then all this flow of migrants will be directed towards your societies," he warns. "Greece used to say it before but back then, no-one listened."

Each evening, as the sky over Crete turns orange, the coast guard escorts a group of migrants to port and on to the night passenger ferry for Athens.

When the number of arrivals climbed earlier this month, they struggled to find space on board.

The minister insists the suspension of asylum rights is a temporary step, most likely only for summer.

High winds rather than government resolve seems to have slowed the flow of boats for now.

But the move has raised concerns about how readily governments can discard a fundamental right in the name of security. It also leaves huge questions for those like Mustafa from Sudan, who fled war, and have now been detained in Europe.

Related topics

- Published22 October