Israeli settlers in West Bank see Trump win as chance to go further

Israel continues to build settlements in the occupied West Bank

- Published

On a clear day, the skyscrapers of Tel Aviv are visible from the hill above Karnei Shomron, an Israeli settlement in the occupied West Bank.

"I do feel different from Tel Aviv," said Sondra Baras, who has lived in Karnei Shomron for almost 40 years. "I'm living in a place where my ancestors lived thousands of years ago. I do not live in occupied territory; I live in Biblical Judea and Samaria."

For many settlers here, the line between the State of Israel, and the territory it captured from Jordan in the 1967 Middle East war, has been erased from their narrative.

The visitors' audio-guide at the hill-top viewpoint describes the West Bank as "a region of Israel" and the Palestinian city of Nablus as the place where God promised the land to the Jews.

But formal annexation of this territory has so far remained a dream for settlers like Sondra, even while settlements - viewed as illegal by the UN's top court and most other countries - have mushroomed year after year.

Now many see an opportunity to go further, with the election of Donald Trump as the next US president.

"I was thrilled that Trump won," Sondra told me. "I very much want to extend sovereignty in Judea and Samaria. And I feel that's something Trump could support."

Settler leader Sondra Baras has lived in the West Bank for nearly four decades

There are signs that some in his incoming administration might agree with her.

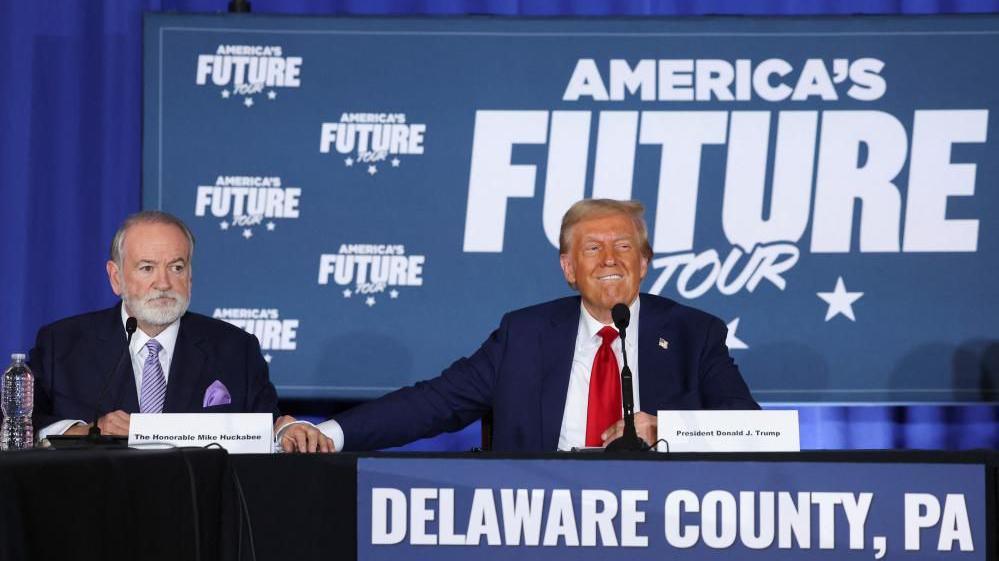

Mike Huckabee, nominated as Trump's new ambassador to Israel, signalled his support for Israeli claims on the West Bank in an interview last year.

"When people use the term 'occupied', I say: 'Yes, Israel is occupying the land, but it's the occupation of a land that God gave them 3,500 years ago. It is their land,'" he said.

Mike Huckabee, seen with Donald Trump on the campaign trail last year, is the president-elect's nominee for US Ambassador to Israel

Yisrael Gantz, head of the regional settlement council that oversees Karnei Shomron, says he has already noticed a change in tone from the incoming Trump administration as a result of the 7 October 2023 Hamas attacks on Israel, which triggered the war on Gaza.

"Both here in Israel and in the US, they understand that we must apply sovereignty here," he told me. "It's a process. I can't tell you it will be tomorrow. But in my eyes, the dream of a two-state solution is dead."

US President Joe Biden has always maintained the US position in support of a future Palestinian state alongside Israel. Asked whether he was hearing something different from the incoming Trump administration, Mr Gantz replied, "Of course, yes."

But there are also signs that Israelis lobbying for annexation of the West Bank - some of them in cabinet positions - might be disappointed in Trump's decisions.

Their hopes have been fuelled by memories of his first term as president, during which he broke with decades of US policy - and international consensus - by recognising Jerusalem as Israel's capital, and Israeli sovereignty over the occupied Golan Heights, which were captured from Syria in 1967.

Many Israelis welcomed Donald Trump's election win in November

But supporting annexation of the West Bank would be a much bigger and thornier issue for Trump.

It would likely alienate Washington's other key ally, Saudi Arabia, complicating Trump's chances for a wider regional deal.

It could also alienate some moderate Republicans in the US Congress, concerned about the impact on West Bank Palestinians, and their future status under Israeli rule.

Settler leader Sondra Baras told me that West Bank Palestinians who did not want to live in Israel could "go wherever they want".

Challenged on why they should leave their homeland, she said: "I'm not kicking them out, but things change. How many wars did they start? And they lost."

"If sovereignty were to go forward, there would be a lot of yelling and screaming, absolutely," she continued. "But at some point, you create a fact that's irreversible."

Shortly after Trump's election victory last November, Israel's far-right Finance Minister, Bezalel Smotrich, publicly called for annexing the Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

"2025 must be the year of sovereignty in Judea and Samaria," he said.

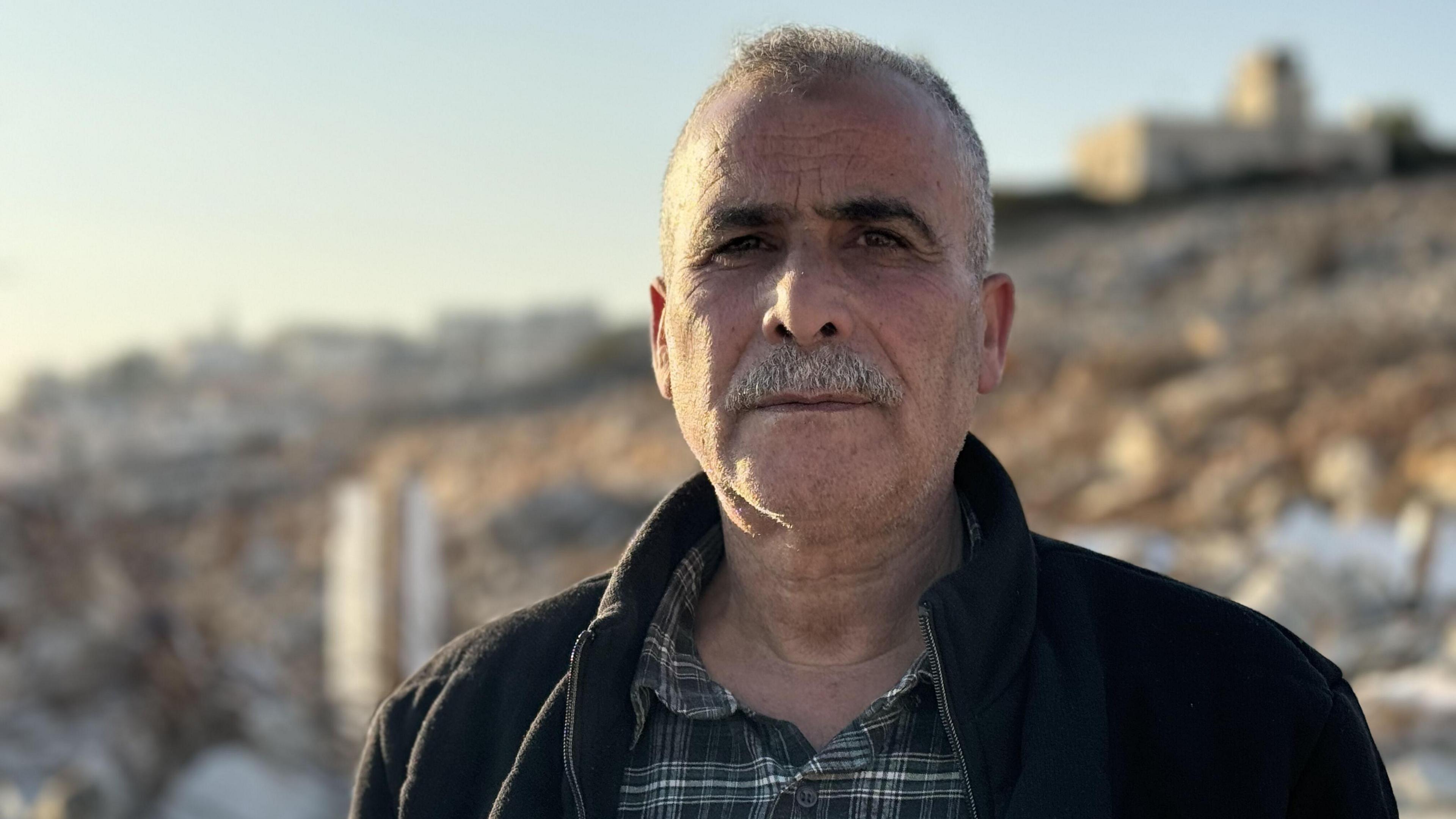

Mohaib Salameh's home on the outskirts of Nablus has been demolished

Whether or not the new US president agrees, many Palestinians say discussion of formal annexation misses the point - that Israel is, in practice, already annexing territory here.

One of them is Mohaib Salameh. He leads me across the rubble of his family home, built on private Palestinian land, on the outskirts of Nablus. The building was ruled illegal by an Israeli court last year and demolished.

Israel has full control over security and planning in 60% of the West Bank on an interim basis, as outlined in the Oslo peace accords three decades ago.

While settlements are expanding, permits for Palestinian homes are almost never granted. And lawyers say demolitions like this are increasing.

Mohaib Salameh says his now-demolished home posed no threat to the Israelis

"This is all part of policies to force us to leave," Mohaib said. "It's a policy of forced migration. What difference does it make to them [Israelis] if I build here or not? We pose no threat to them."

Palestinians are also increasingly being forced off their land by violent Israeli settlers - who have been sanctioned by the US and UK, but largely left unchallenged by Israeli courts at home.

This image, provided by an Israeli human rights organisation, shows what they describe as teenage settlers attacking Palestinian homes in the southern West Bank

Activists say more than 20 Palestinian communities in the West Bank have been expelled over the past few years by increasingly violent attacks, and that settlers are now encroaching into new areas outside Israel's interim civil control.

Mohaib told me that no US president had ever protected Palestinians, and that he doesn't believe Donald Trump will either.

America's next president is widely seen as a friend of Israel.

But he's also a man who also likes closing deals - and avoiding conflicts.

- Published27 August 2024

- Published6 January

- Published3 September 2024