India's biofuel drive is saving billions but also sparking worries

Indian government says ethanol blending has cut 69.8 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions since 2014

- Published

India's drive to blend more biofuels with petrol has helped the country cut millions of tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions and save precious dollar reserves.

But it has also sparked worries among vehicle owners and food policy experts about its potential impact on fuel efficiency and food security.

Last month, India achieved its objective of blending 20% ethanol with petrol, known as E20, five years ahead of its target.

The government views this as a game changer in reducing carbon emissions and trimming oil imports. Since 2014, ethanol blending has helped India cut 69.8 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions and saved 1.36 trillion rupees ($15.5 bn; £11.5 bn) in foreign exchange.

A study by Delhi-based think tank Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) shows that carbon dioxide emissions, external from road transport in India will nearly double by 2050.

"The demand for fuel is only going to increase and shifting to ethanol-blended petrol is absolutely necessary to cut down emissions," Sandeep Theng from the Indian Federation of Green Energy, an organisation that promotes green energy, told the BBC.

But many vehicles in India are not E20-compliant, making their owners sceptical about the benefits of the policy.

Hormazd Sorabjee, editor of Autocar India magazine, said that ethanol has a "lower energy density than petrol and is more corrosive". This results in lower mileage and exposes certain vehicle parts to a greater risk of wear and tear.

Mr Sorabjee added that some manufacturers like Honda have been using E20 compliant material since 2009, but many older vehicles on Indian roads are not E20 compatible.

While there is no official data on the impact of of E20 fuel on engines, consumers routinely share anecdotes about their vehicle's deteriorating mileage on social media.

Many standard insurance policies in India also don't provide cover for damage due to the use of non-compliant fuel, a top executive at online insurance platform Policybazaar, who wanted to stay anonymous, told the BBC.

"Consumers need to take add-on policies but even those claims can be denied or downgraded based on fine print of the policy," he added.

The federal petroleum ministry has described these concerns as "largely unfounded".

In a post on X, the ministry said that engine tuning and E20-compatible materials could minimise the drop in mileage. It also advised replacing certain parts in older vehicles, saying the process was inexpensive and "easily done during regular servicing of the vehicle".

Expansion of ethanol use could mean diverting more farm produce into manufacturing fuel

Mr Sorabjee told the BBC that while mileage concerns are real, they are "not always as bad as made out to be".

The bigger concern, he said, was the potential damage to vehicle materials due to the corrosive properties of E20.

Some vehicle manufacturers are offering ways to mitigate this.

Maruti Suzuki, India's biggest four-wheeler maker, is reportedly likely to introduce an E20 material kit , externalthat could cost up to 6,000 rupees ($69; £51). The kit will reportedly replace components like fuel lines, seals and gaskets. Bajaj, a leading Indian two-wheeler maker, has advised using a fuel cleaner, external that could cost around 100 rupees ($1.15; £0.85) for a full tank of petrol.

But not all vehicle-owners are convinced. Amit Pandhi, who has owned a Maruti Suzuki car in Delhi since 2017, is unhappy that petrol pumps don't offer the choice to opt for a blend other than E20.

"Why should I be forced to buy petrol that offers less mileage and then spend more to make the materials compliant?" he asked.

In 2021, a document on India's transition to E20 published by Niti Aayog, a government think tank, had highlighted some of these concerns. It recommended tax benefits for buying E20 compliant vehicles, along with a lower retail price for the fuel.

The government has defended its decision to not pass the recommendations, saying that at the time of the report's release, ethanol was cheaper than petrol.

"Over time, procurement price of ethanol has increased and now the weighted average price of ethanol is higher than cost of refined petrol," the petroleum ministry said, external earlier this month.

India is looking to increase ethanol-blending in petrol in the coming years

It's not just consumers - the government's blended fuel push has also raised concern among climate researchers and food policy experts.

Ethanol is produced from crops like sugarcane and maize, and expanding its use means diverting farm produce into manufacturing more fuel.

In 2025, India would need 10 billion litres of ethanol to meet its E20 requirements, according to government estimates. The demand will balloon to 20 billion litres by 2050, according to Bengaluru-based think tank Center for Study of Science, Technology and Policy (CSTEP).

Right now, sugarcane is used to produce about 40% of India's ethanol.

This puts India in a bind. It has to choose between continuing its reliance on sugarcane - which has a higher yield for ethanol but is water-intensive - or using food crops like maize and rice to produce the fuel.

But the shift comes with its own challenges.

In 2024, for the first time in decades, India became a net importer of maize, using large amounts of the crop to make ethanol.

Ramya Natarajan, a research scientist at CSTEP, said the diversion of produce had a significant impact on the poultry sector, which now has to spend more to buy corn for feedstock.

Moreover, this year, the Food Corporation of India (FCI) approved an unprecedented allocation of 5.2 million tonnes of rice for ethanol production. The rice in FCI stocks is earmarked to be given to India's poor at a subsidised rate.

The policy could lead to an "agriculture disaster in a couple of years", said Devinder Sharma, a farming sector expert.

"In a country like India, where 250 million people go hungry, we cannot use food to feed the cars," Mr Sharma said.

To meet the demand for ethanol through corn and sugarcane in a 50-50 ratio - as outlined by Niti Aayog - India would have to bring in an additional eight million hectares of land under maize cultivation by 2030, unless there is a drastic increase in yield, according to CSTEP.

But even that could lead to problems.

"If farmers replace rice or wheat cultivation with maize, that would be sustainable because we have enough surplus of these crops. But we need other crops like oilseeds and pulses too," Ms Natarajan said.

Ms Natarajan added that continuing with the E10 blend - petrol mixed with 10% ethanol - would have been a more ideal choice.

India, however, is planning to go even beyond E20.

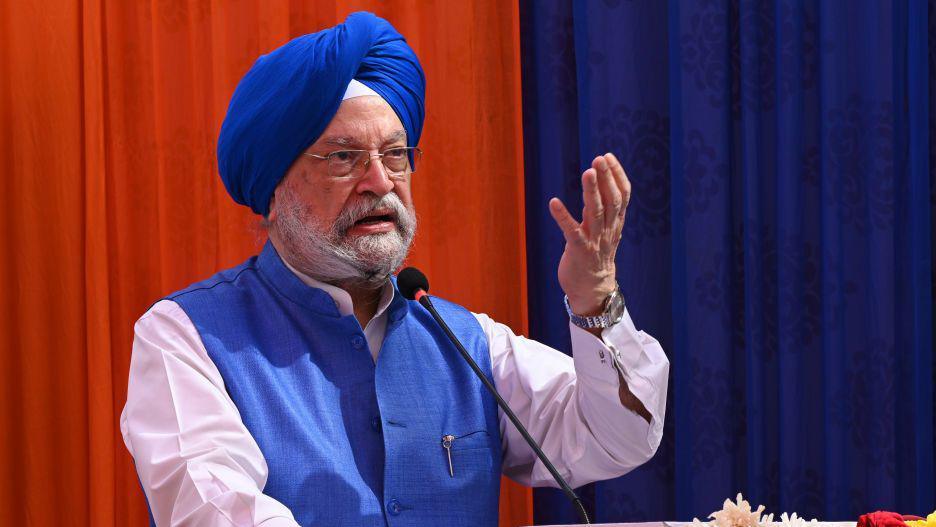

"The country will now gradually scale towards E25, E27, and E30 in a phased, calibrated manner," Petroleum Minister Hardeep Puri said recently.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, external, YouTube, external, X, external and Facebook, external