Why are there so many people in Scotland's jails?

The number of inmates in Scottish prisons is nearly at a record level

- Published

The Scottish prison system is "bursting at the seams", according to First Minister John Swinney, and another emergency measure has been announced.

A controversial plan to restore automatic release for long-term inmates has been shelved, but short term prisoners will now be freed sooner - after 40% of their sentence rather than at the half way point.

The prison population is currently sitting at around 8,300 - about a 100 short of the all-time high of 8,420 recorded in 2012.

So why is Scotland's prison population so high - and what can be done about it?

One of the highest incarceration rates in Europe

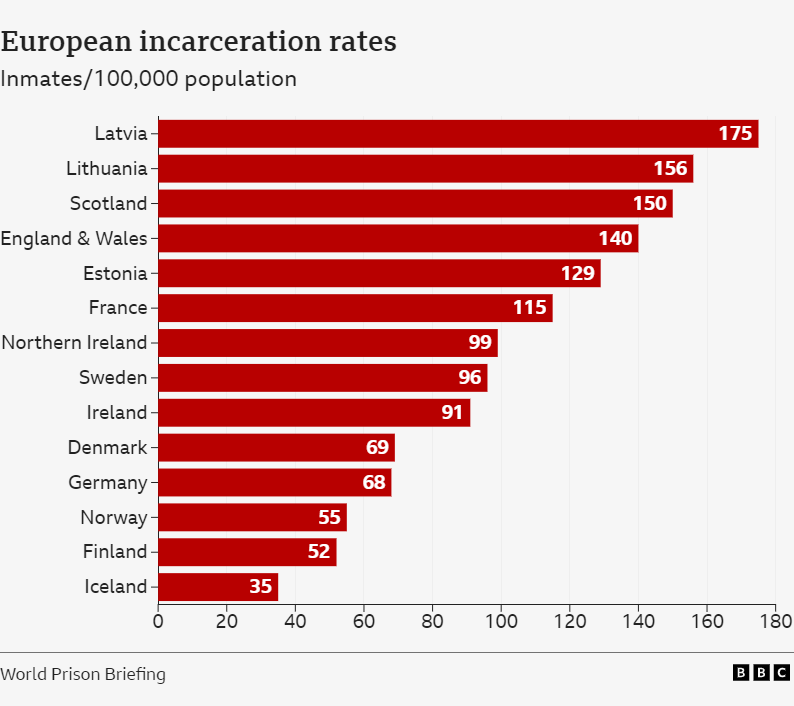

Both Scotland - and other parts of Britain - have a higher proportion of their citizens in prison than most other countries in Europe.

Typically in Scotland, England and Wales there are between 130 and 150 people in prison per 100,000 population - a rate surpassed in Europe by only a handful of countries such as Latvia and Lithuania.

Scandinavian countries have far lower incarceration rates - and in Iceland the equivalent figure is about 36, according to recent data from World Prison Brief., external

Worldwide there are some countries that imprison a far greater proportion.

El Salvador tops the list with more than 1,600 inmates per 100,000, due in part to a mass incarceration strategy to crack down on gangs.

The USA has more than 1.8 million people behind bars, the biggest prison population in the world, representing more than 500 inmates per 100,000 population.

Criminologists say there's little linkage between crime levels and incarceration rates - the differences seem to be largely driven by policy and cultural expectations about how society should respond to crime.

High numbers of remand prisoners

Roughly a quarter of inmates in Scotland's jails are people who have been detained but are awaiting conviction or trial - known as being "on remand".

Recent figures, external indicate the median time spent being held this way is 79 days - but about 30% of remand prisoners are detained more than 140 days.

Many of those inmates will eventually be cleared or will receive non-custodial sentences.

The total prison population fell due to public health measures during the Covid pandemic - but a subsequent backlog of court cases has been a problem.

Public health measures during the Covid pandemic resulted in a backlog in the court system

Prison reform group Howard League Scotland believes the number of non-convicted people behind bars is far too high, describing is as a "scandal" , external

But about half of remand prisoners have been detained for alleged crimes of violence, so moves to increase the numbers released on bail could be controversial.

What else is driving up prison numbers?

Since 2019 there has been a presumption against short sentences of 12 months or less - a policy aimed at keeping less serious offenders out of jail.

That means that if a court sentences someone to less than a year in jail - it must provide an explanation for why it thinks no alternative sentence would do.

But it's not an outright ban on short sentences, and many courts continue to impose them.

For more serious crimes, there's been a long term trend for longer sentences.

The number of people sentenced for domestic abuse and sexual crimes has also risen, possibly reflecting a greater readiness of people to report such offences.

In recent years growing numbers have been brought to justice for historical sex crimes deemed so serious that only a custodial sentence is appropriate.

Prior to 2016, people serving sentences of four years or more were automatically released on licence after serving two thirds of their prison term.

That was changed, meaning they would only be automatically released if they had less than six months to serve, leading to upward pressure on prison numbers.

Reversing that policy was a possible emergency measure considered by the government - but it has stopped short of that for now.

What more can be done to cut the prison population?

Dr Kirstin Anderson, a lecturer in criminology at Edinburgh Napier University, believes the starting point is sentencing decisions.

"You need to look very carefully at everyone who goes to prison in Scotland and ask is it absolutely necessary for them to be there - and if not, then they should not be going," she says.

In order to divert people away from custody, she believes, there must be practical solutions available.

"These could be home detention curfews, it could be participation in various programmes if the crime relates for instance to drug use, it could be electronic tagging."

Criminologist Dr Kirstin Anderson believes that prison is not the best place for all offenders

But in order to work, these need to be well-resourced - which in the current financial climate is difficult.

She cites the recent closure, due to lack of funds, of the "amazing" Turning Point 218 project in Glasgow - which provided an alternative to custody for women.

"Sometimes sentencers are in a position where they don't want to send someone to custody, but there's not another option which I think is a huge problem."

Dr Anderson also believes more could be done to remove the barriers that prevent people "progressing" out of the prison system.

"There are people in prison who can't access offender behaviour programmes - things like sexual offender or addiction programmes," she explained.

"They can't finish their sentences and get out of prison until they've accessed these programmes so they are stuck in jail for sometimes years longer than necessary."

Progressive approach or soft justice?

Debate on prison reform often references the so-called Nordic system - where Scandinavian countries jail fewer people and place a strong focus on rehabilitation.

Norway for instance has a maximum prison sentence of 21 years.

Prisons are generally smaller with better facilities for inmates and an emphasis on training and skill-building.

But the Scottish Sentencing Council, external recognises that rehabilitation of the offender is not the only function of a sentence. Punishment, expressing society's disapproval and protection of the public are also important.

The possibility that long term prisoners could again be automatically released two thirds through their sentence prompted a joint statement, external from Victim Support Scotland, Women's Aid, Rape Crisis Scotland and the domestic abuse charity ASSIST

"We note that these proposals would apply to prisoners who have been previously denied parole and would be back-dated to 2016," they wrote.

"We therefore have grave concerns about victims’ and public safety."

Balancing the rights of prisoners and victims is a difficult and sensitive issue.

Dr Anderson accepts "it's messy" - but she thinks with the right resources and protections they can be reconciled.

"Most victims of crime say ultimately that what they want is to ensure that no-one experiences what they have.

"We know that imprisonment, for most people doesn't address why the harm was committed and it doesn't fix that."

A smaller prison population could allow the prison service to work far more effectively with the inmates that remain, she argues.

"When you have a prison that's overcrowded, just running the basics takes longer - so if there are people in that establishment who don't really need to be there, they shouldn't."