Why did a UK college repatriate Aboriginal spears?

Representatives from the Aboriginal community saw the spears at Trinity College's Wren Library ahead of the repatriation ceremony

- Published

Aboriginal spears taken on the day British explorer James Cook made first contact with Australia will soon be on their way home.

The weapons were taken by the crew of HMB Endeavour on 28 April 1770 and four of the spears were donated to the University of Cambridge's Trinity College, external the following year.

The college decided to repatriate them following discussions with the La Perouse Aboriginal Community. A new visitor centre will be built to display them, close to where they were made at Botany Bay, Sydney.

So, what does the return of the 18th Century spears mean for the descendants of their makers and why did Trinity College decide to permanently repatriate them?

What happened on 29 April 1770?

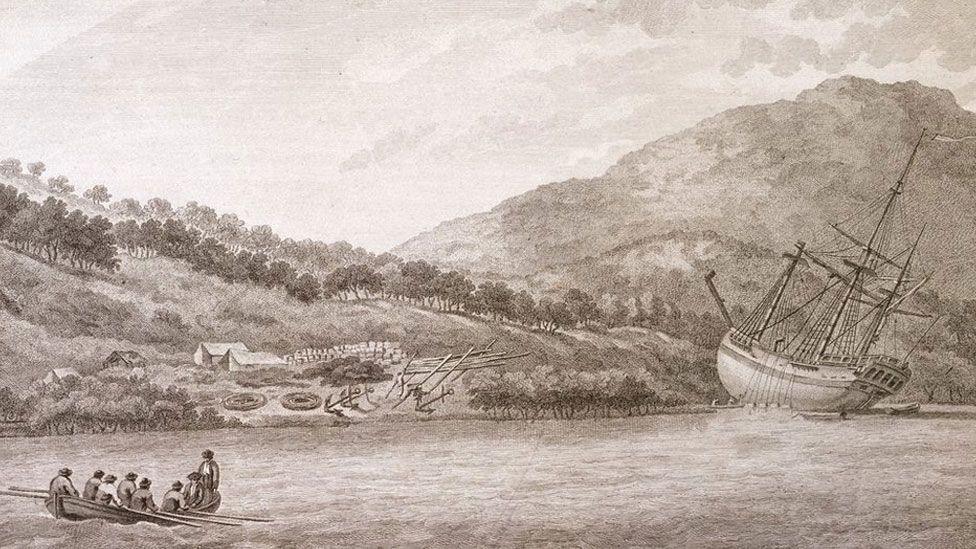

HMB Endeavour sailed for several years around the South Pacific before landing in eastern Australia in 1770

When Lt Cook set sail in 1768, he carried with him secret orders from the British Admiralty to seek out Terra Australis Incognita - the unknown southern land, external.

He was the captain of HMB Endeavour and Joseph Banks was its lead scientist when the ship arrived at the eastern part of Australia on 29 April 1770.

Their attempt to land at Botany Bay was resisted by men of the Gweagal people, so the crew fired upon them, The University of Cambridge's Prof Nicholas Thomas, said.

He added: "Those men withdrew and the British advanced inland a little way and came across a camp and found a large number of spears and thought at first they were weapons.

"Joseph Banks thought they were poisoned, so they gathered up 40 to 50 spears and took them away in an act of disarmament."

Lt Cook quickly realised they were fishing spears and what was thought to be poison was resin, used to attach the bone tips to the multi-pronged spears.

A few months after the Endeavour's return in 1771, the spears were donated to Trinity College by former student Lord Sandwich, the First Lord of the Admiralty.

Why are the spears being returned to Australia?

Prof Nicholas Thomas (back row second left) said returning the spears to Australia was the right thing to do

"This was a very clear-cut case where artefacts were taken without the consent of the owners," said Prof Thomas, who is also the director of the University of Cambridge's Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA), external and a Trinity College Fellow.

About 100 other items from the Endeavour voyage were donated to the college, mostly from Tahiti and New Zealand, but unlike the spears, they were obtained through bartering or as gifts, he said.

Initially, the spears were displayed at Trinity's Wren Library, but since 1914, they have been on loan to MAA.

They also returned to Australia for exhibitions in 2015 and 2020.

Prof Thomas said: "The more recent exhibition led to a lot of engagement and interest from Gweagal people.

"That strengthened the feeling from community that they would be of tremendous value to have them back on display 'on Country', where they came from.

"Given the way these issues have been thought through by curators and others in the heritage sector in the UK, the view from the museum and the college was it was the right thing to do."

'It absolutely feels like a homecoming'

Noeleen Timbery said it is important to remember the spears were made for a purpose and not as artefacts

"These spears were taken away during the first contact between Europeans and the first nations people of Australia," said Noeleen Timbery, from the La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council.

"That contact's always had a narrative as a one-sided story, so having tangible objects that have survived from that time can tell us a lot about the people who made them, it brings a different narrative and story to the beginning of the shared history of Australia."

Ms Timbery was among Aboriginal representatives who attended the repatriation ceremony held in Trinity College's Wren Library on Tuesday, but has also visited the archives of UK museums, where similar items are stored.

"They were made for a purpose and that's forgotten when they are seen as artefacts," she said.

It made Ms Timbery wonder "what else is in the back areas of UK museums that we don't know about and how can we connect to them".

For her, "it's important to do that on Country" - the term often used by Aboriginal peoples, external to describe the lands, waterways and seas to which they are connected.

"So, when we talk about bringing them back to Country, it's almost like reconnecting them with land, with spirit, with a time gone by," she said.

"It absolutely feels like a homecoming."

'We hope that other UK institutions will take a similar approach'

Ray Ingrey brushed the spears with gum leaves during the ceremony and said "we were announcing our arrival to the spears and telling them we were taking them home"

Gujaga Foundation director Ray Ingrey, who is a Dharawal person from the La Perouse Aboriginal community, said: "The timing was right. With a newly developed centre we would absolutely have museum-grade security for them to continue to be cared for another 250 years."

The spears were made from woods that can still be sourced in and around Botany Bay and other places south of Sydney.

"We have senior people within our community that teach that practice to this day - how to make them, to use them, fish with them," said Mr Ingrey.

"So, there is still the craftsmanship to make spears the old way and now we will be able to see them side-by-side with the spears made 254 years ago."

He praised the "really unique" work of the museum and Trinity College to make the return possible and added: "We hope that it means our story can be shared and other museums and cultural institutions across the UK will take a similar approach.

"And in lieu of the old spears, our community, through senior Elder Uncle Rod Mason, has made spears to go on display in the museum - so our relationship with Trinity College isn't just transactional, but building a relationship to tell the right balancing story."

The spears are known as the Gweagal spears, named for the Gweagal clan of the Dharawal nation

Follow East of England news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp us on 0800 169 1830

- Published23 April 2024

- Published30 November 2023

- Published10 April 2023