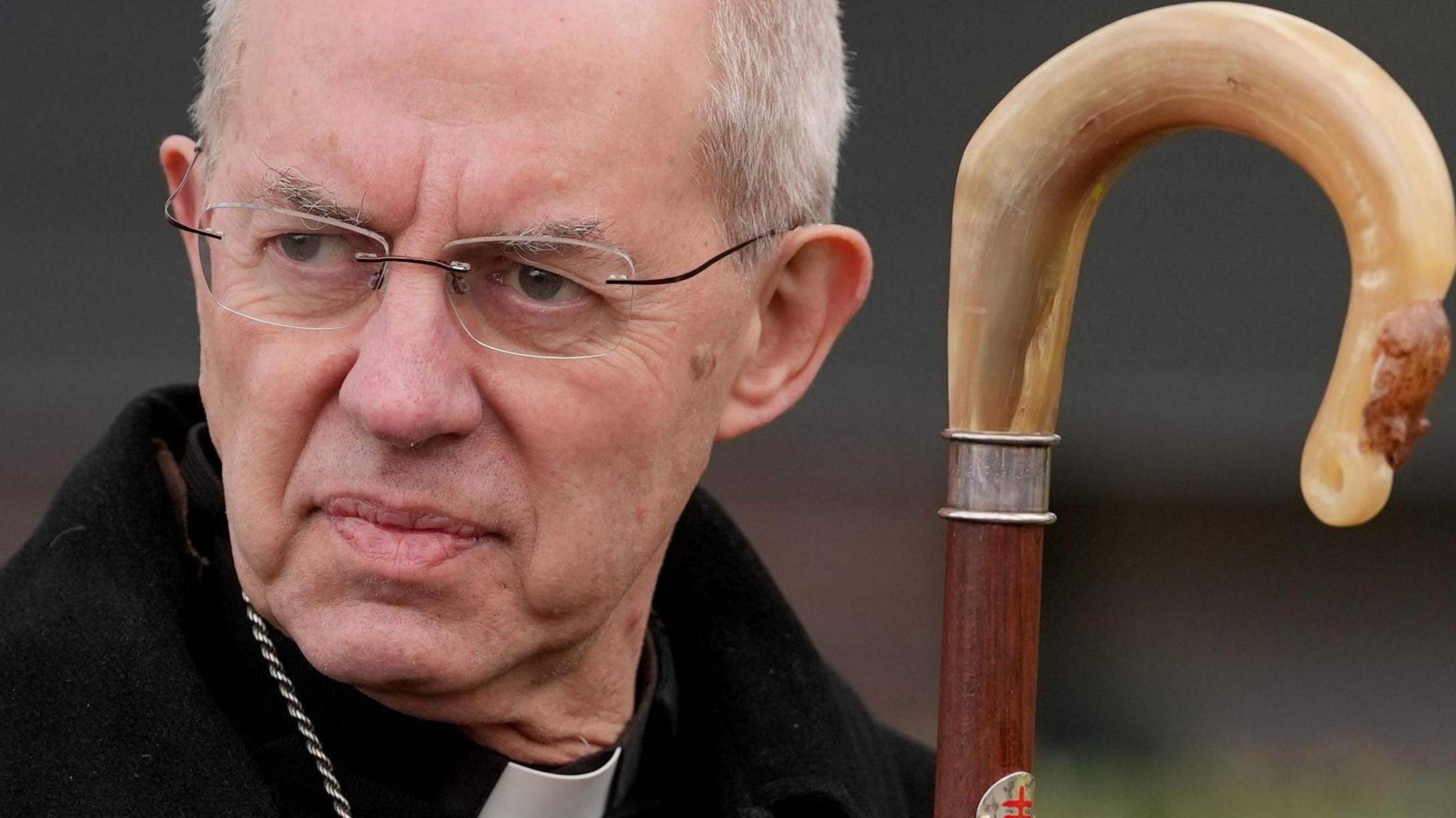

Church at precarious moment after Welby resignation

- Published

After a turbulent week and the dramatic resignation of the man that leads it, the Church of England is trying to take stock at what is a precarious moment.

There are many within the faith who have experienced this as a deeply painful time and for whom the direction the institution takes now is profoundly important.

For some, including abuse victims, that pain has come from the stark reminders that the Church is still not a place people can trust to do all the right things when it comes to keeping people safe.

Among them, there will be relief that Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby has stepped aside as someone who had lost credibility on the issue which would make it difficult to sanction other clergy for not doing enough.

But some Anglicans have been upset because they feel that Justin Welby had done much good and, however slowly, was trying to steer the Church in a better direction.

As a dispassionate observer of lots of faith institutions, I have felt there are few that match the Church of England for its wide range of views within the same fold.

While there are women bishops, there are also male bishops who are allowed to refuse to ordain women.

While the Church has voted to move to introduce prayers for same-sex couples, clergy will also be allowed not to lead such blessings if they feel they do not want to.

Attending the Church’s national assembly, its General Synod, is eye-opening in the ferocity of debate over issues across the board, often reflecting the polarisation in modern Britain on many issues.

But at the end of each day, people who have been at each other’s throats during debates, come together in worship.

Mr Welby has undoubtedly seen it as a big part of his job to hold together very different factions within the Church of England and, even more difficult, in the wider global Church, the Anglican Communion of 85 million people.

For him this has been about the survival of a Church that, at home, is already experiencing falling numbers, with the number of people in England and Wales describing themselves as “Christian” falling below 50% for the first time, with a huge rise in those who do not align themselves with any religion

He has expended a huge amount of energy in this endeavour of finding common ground through 12 years during which there has been other momentous social change, and at times has shown himself to be an astute political operator.

Early in his tenure as Archbishop of Canterbury, he was credited with helping usher through the vote that allowed women to become bishops, being supportive of the move through often tempestuous division.

On the question of sexuality and same-sex unions, Mr Welby has had a complicated journey - shifting from a very conservative position to one where he was supportive of the measure that was eventually voted through to allow the blessing of same sex unions.

But observers saw it as a bit of a fudge by the Church and by Mr Welby.

Debate did not start with the premise that gay people were equals in the Church and deserved marriage equality (something that was not even put to a vote), and the result did not represent a significant change in Church teaching.

But neither did Church leaders condemn gay unions as some traditionalists had wanted. There was even later clarification to African Churches that the blessing prayers that were voted through were to bless the individuals in the same-sex union and not bless the union itself.

It has been a theme that in being so focused on holding things together, and sometimes appearing to try to be all things to all people, Mr Welby has been viewed by many on both right and left as not taking a principled stand.

He has behaved like a politician and in some ways has faced the downfall of a politician or executive, rather than that of spiritual leader.

What some Anglicans are calling for now is more of a theologian to lead the Church rather than someone seen more of an executive, but in a modern world with modern responsibilities, others worry that there needs to be an element of the executive leader that is needed.

The tribalism and polarisation that is often evident in the Church makes some anxious that a skilled politician at the top is the only way the institution does not start to fracture.

Whatever skill set Archbishop Welby may have had, in not doing enough on the important issue of safeguarding through rigorously pursuing abuse cases when they were brought to his attention and ensuring others did the same, much trust in the Church was lost.

Dealing decisively with that one crucial issue might well have helped in his mission to build unity and in helping stem a decline in the numbers of faithful.

- Published13 November 2024

- Published7 November 2024