Did postal vote delays affect Scotland's election?

- Published

From the day it was called, there was much talk about the fact the general election would be held when many Scottish schools were on holiday.

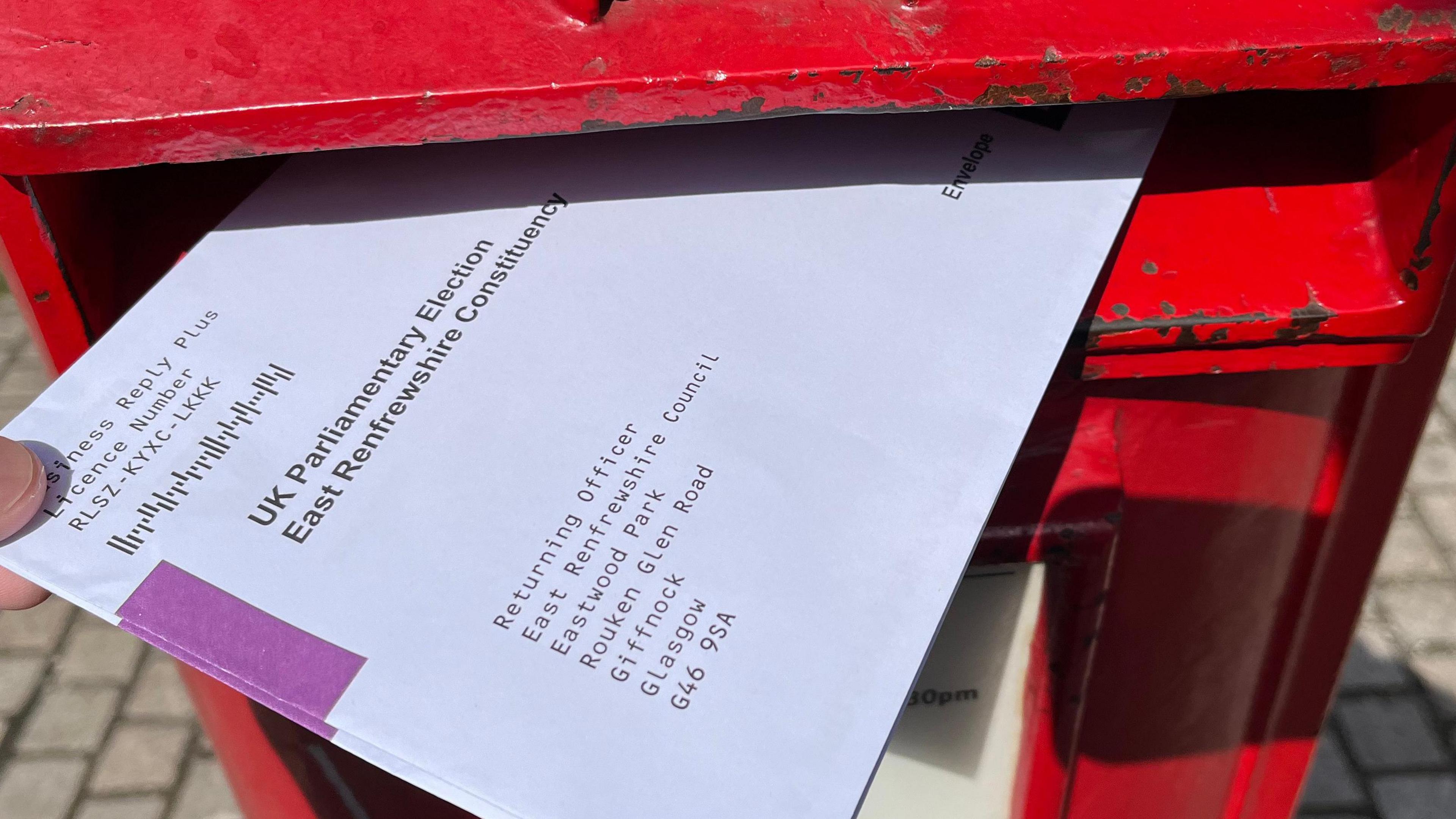

This prompted concerns about postal voting, with many stories of families setting off abroad before their ballots had hit the doormat.

People who had followed the instructions were missing out on their right to vote, and parties were convinced that it could make all the difference with polls on a knife edge.

But how widespread an issue was it, in the end? Could the collision of polling day and the school holidays have actually made the difference in some key marginal seats?

Postal voting took a leap post-Covid, but has actually been steadily on the rise for years.

At the 2019 general election, 21% of Scots signed up for a mail-in ballot. In 2024 that figure rose to 24% - just shy of a million voters.

It does vary quite a bit across the country. In Edinburgh West, fully a third of the electorate opted for a postal vote, while in Coatbridge and Bellshill only 16% did.

City of Edinburgh Council had to process and send out more than 100,000 forms across five constituencies - no small feat for a snap election, and perhaps a clue as to why some took longer to arrive than others.

The council ended up opening an emergency facility for people at risk of missing out to collect and submit their postal ballots.

People who sign up for a postal ballot are always far more likely to actually register a vote, with about 83% of those issued being sent back in 2017 and 2019.

So can we work out, from changes in that postal turnout figure, whether the holidays denied a significant group of voters from having their say?

City of Edinburgh Council offered people an emergency facility to fill in postal ballots

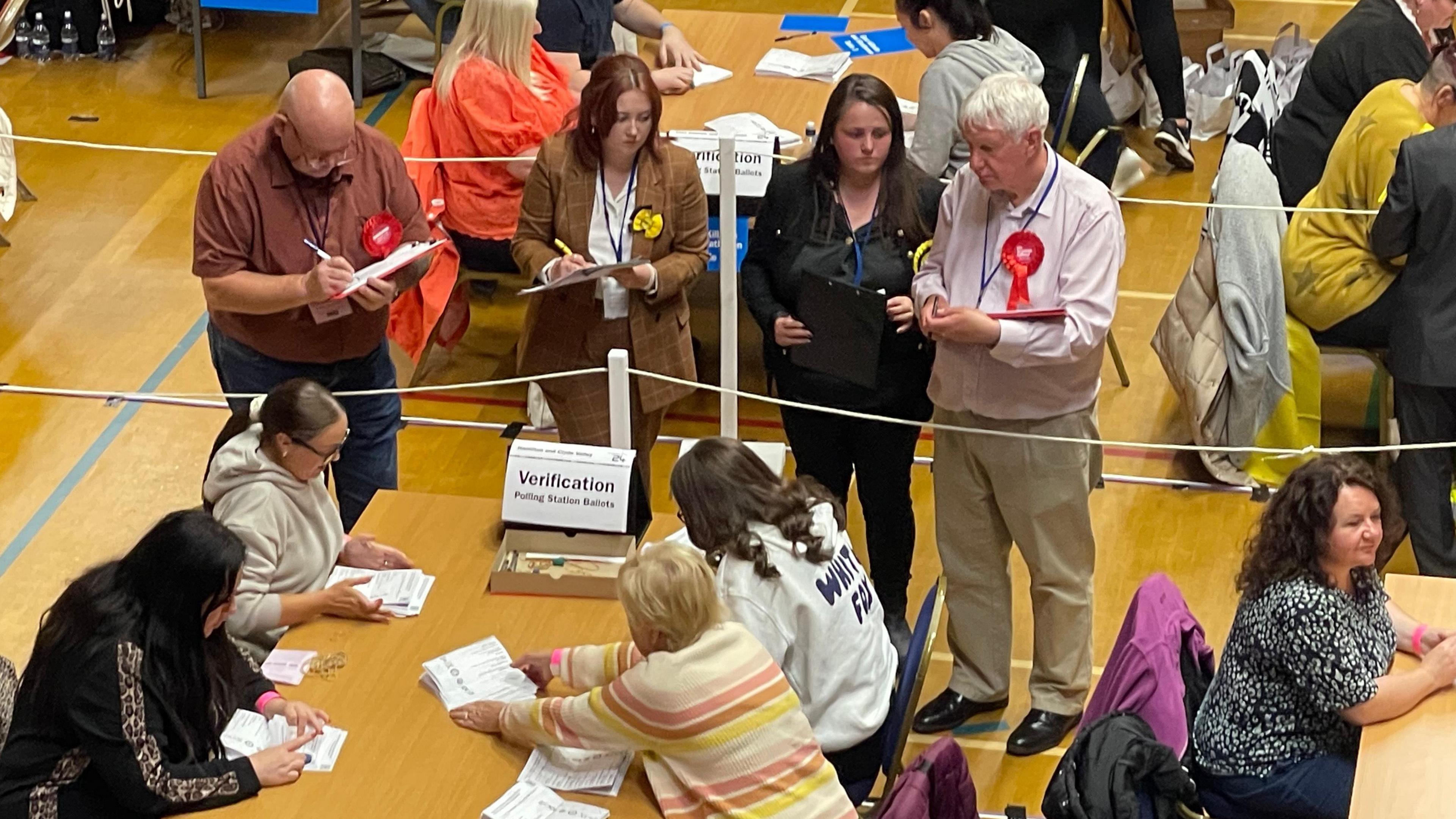

Let’s start in Glasgow. Boundary changes mean the city has gone from seven seats to six, with the lines on the electoral map shifting all over the place - but we can still work out the average return rate for postal votes across the city.

In 2019, it was 76.5%. This year, it was 73.5% - down three percentage points.

That’s not nothing. But fewer voters in Glasgow are registered for postal votes, below 20% in most of the seats. And 3% of under a fifth of the electorate doesn’t amount to very many votes.

Even if you take a leap and assume the drop in turnout was entirely caused by the holidays, and that every single spurned postal voter would have backed the SNP, it still wouldn’t have come close to holding off the Labour surge.

The same is true in Edinburgh, where postal voting is much more common.

In 2019 the average postal ballot return rate for the five city constituencies was 84.3%. This time it was 83.2% - down over a full percentage point, but again not nearly enough to make a difference to the outcome.

Labour won every Glasgow seat by a convincing margin

So let’s look at Scotland’s most marginal seats, where fewer than a thousand votes decided the outcome.

Dundee Central is now the most marginal seat in Scotland, despite being the safest one going into the poll. Chris Law held on for the SNP, but there were only 675 votes in it.

What about postal ballots?

Boundary changes make this hard again, but the average return rate between the old Dundee East and West seats was 83.8% in 2019.

For the new Central seat, made up of big chunks of East and West, it was 79.3%. A drop of 4.5 percentage points (pp).

If the return rate had held steady where it was, that would account for an extra 696 votes - that being 4.5% of the 15,472 postal ballots issued.

Enough in theory to swing the seat for Labour, had pretty much all of them gone the same way.

There’s another marginal seat next door, in Arbroath and Broughty Ferry. The SNP won by 859 votes - but the fall in postal turnout across the area was about 4pp.

If the return rate had held up, that could have meant an extra 812 votes - incredibly close to the eventual majority.

Chris Law held on to his seat in Dundee - but only by 675 votes

Elsewhere, the Conservatives held Dumfries and Galloway with a 2% majority. Postal voting is more common here, with 28% of voters signed up - but the return rate was down this year by 5 percentage points.

That 5pp drop accounts for 1,116 votes, in a seat with a majority of 930. Enough to make the difference had almost all come in for the SNP.

The picture isn’t particularly uniform, though. Just look at the muddle across the SNP-Tory marginals of the North East.

In Gordon and Buchan - a notional Conservative hold with a majority of 878 - the postal return rate only fell by about 0.4pp, accounting for less than 80 votes.

In West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine, the return rate actually went up.

In Aberdeenshire North and Moray East, which the SNP took from the Tories by 942 votes, the return rate fell by 3pp - accounting for 580 votes.

So in the end, yes, there were a few seats where postal vote returns were down at a level great enough to potentially make a difference to the result.

But we have no evidence about how those people might have voted, and whether it would have been different enough from the broader electorate in the seat to change the result.

What are the chances that almost all of those ballots would have come down for the one party which needed them, in contrast to the rest of the constituency?

Take the remarkable example of Putney in London, where more than 6,500 votes were somehow left out of the result announced on the night due to a “spreadsheet error”. But when they were eventually factored in, they had broken the same way as the rest of the constituency - it only increased Labour’s majority.

We also don’t know for sure that it was definitely the holidays which held the postal return rate down.

There was a pretty sharp decline in overall turnout, with disaffected voters voicing frustration with the political classes generally.

And postal returns do seem to track overall participation, to an extent.

In Scotland, overall turnout for the general election in 2015 was 71.1%. But for the snap contest of 2017 it fell to 66.4% - a drop of 4.7pp.

Postal vote turnout meanwhile fell from 86.6% to 82.9% - a drop of 3.7pp.

And when overall participation ticked back up to 68.1% in 2019, the postal return rate inched up very slightly too, to 83.1%.

So given the fairly drastic fall in overall turnout this time round - it was down to 59.2% in Scotland - it’s certainly possible that voter apathy has been reflected in postal votes too.

This constituency suffered the joint-largest fall in turnout in Scotland

We also can’t entirely blame the school holidays for poor turnout.

Turnout in Scotland fell by 8.4%, which is a bit more than the 7.4% drop in English seats. But in Wales it was down 10.4%, despite the school term still running.

The fall is likely to have been more about the negative feelings of the electorate towards all politicians - by far a more important issue for parties to address.

Look at it this way. Edinburgh North and Leith had the joint-largest fall in turnout in Scotland, down 13.6pp. But postal ballot returns there were down only 1.22pp.

When the SNP are picking over how they lost that seat, they may well be more concerned with the 9,656 voters who stayed at home compared with 2019, rather than the 224 fewer who sent back a postal ballot.

Or they’ll be looking at places like Glasgow North East, where more than half of the voting population didn’t turn up at all.

Equally, when outgoing Tory leader Douglas Ross is weighing up why he lost Aberdeenshire North and Moray East, he may be more preoccupied by the 5,562 votes which went to Reform UK than the 580 postal ballots which might have turned up.

Anyone missing out on the right to vote is obviously something to take seriously, and councils and the Electoral Commission will be looking to learn lessons for future polls.

But it seems the row over postal ballots did not have a decisive impact on the outcome.