'Broken promises' and deadly violence push Himalayan beauty spot to the edge

- Published

For a long time, the history of tiny Ladakh - a stunning region popular with tourists, nestled high in the Himalayas - has been shaped by notions of spirituality, mysticism and a sense of otherworldliness.

But now, its fabled tranquillity has been shattered by deadly violence.

Protests for greater autonomy from India erupted last week and spiralled into clashes between crowds and police in which four civilians were killed and at least 80 injured.

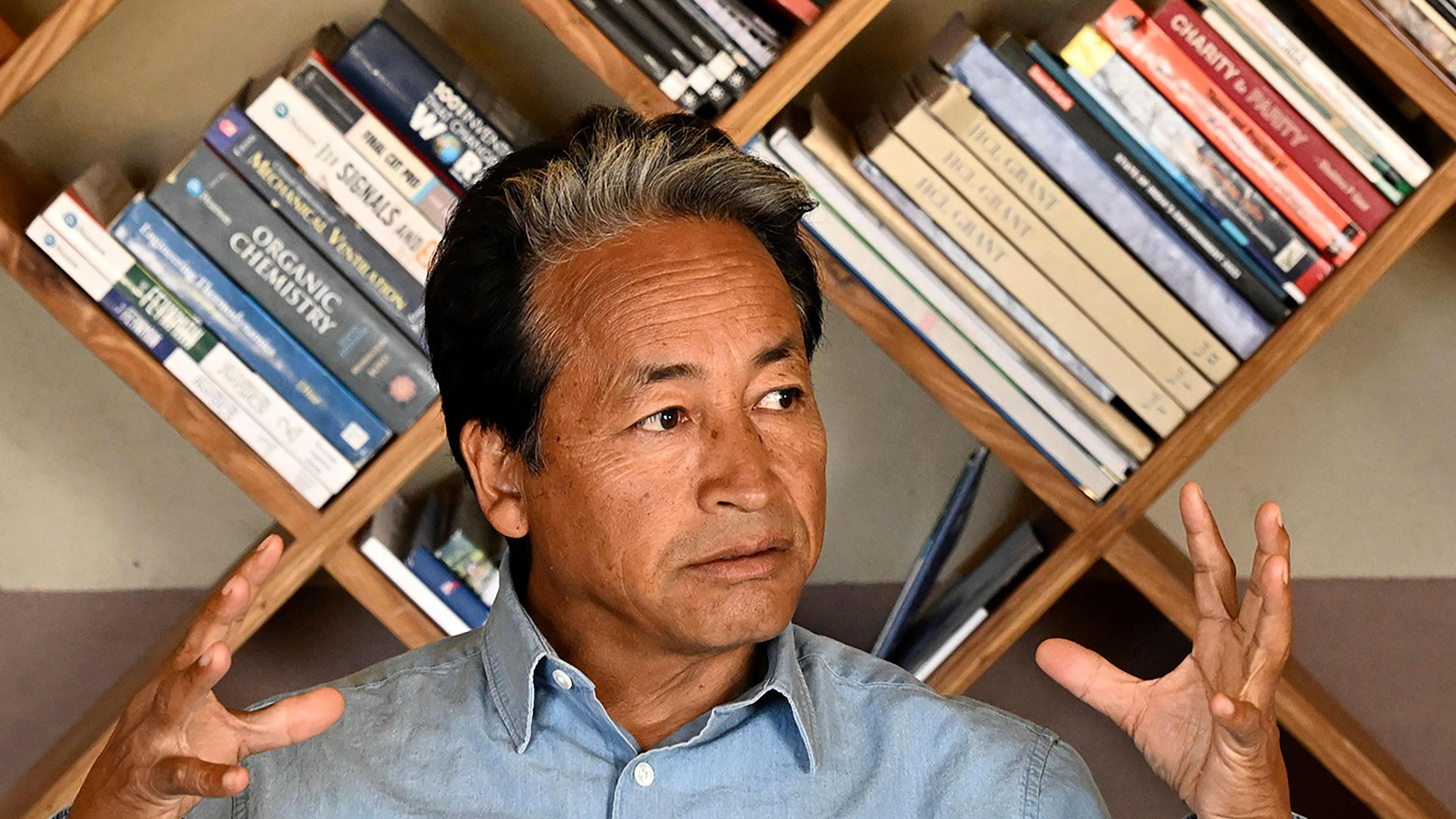

Police arrested Sonam Wangchuk, a prominent scientist and activist who has been at the forefront of protests, alleging he had incited a mob with provocative speeches, a charge he denies. More protesters were then detained as authorities cut internet services, imposed a curfew in the picturesque capital Leh and sent in paramilitary troops.

The discontent in Ladakh is not new, but the violence - the deadliest there for decades - was.

Sandwiched between China to the east and Pakistan to the west, the disputed region with a rich Buddhist past used to be part of Jammu and Kashmir, before the Indian-administered region was split and Delhi imposed direct rule in 2019.

Since 2021, residents have led a peaceful movement seeking statehood, job quotas and special status for Ladakh, which they say is essential to preserve their distinct identity and culture.

"What we saw is the result of years of anger and frustration that has been building up," said one local woman, Jigna, whose real name has been changed to protect her identity.

"It's high time people paid attention to what we want."

The local BJP office was torched during the protest last week

The exact sequence of events last week is still not clear but protesters told the BBC that on 24 September, thousands of people had gathered peacefully in a public park to support Wangchuk and others, who had been on a hunger strike for two weeks.

"At some point, a chunk of people, especially youngsters, walked away from the venue and started a protest rally. Then the violence broke out," said Gelek Phunchok, a businessman who was there.

Dozens were injured and an office of India's governing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was set on fire in the unrest.

Police say they responded to the violence by opening fire, but protesters deny this. An inquiry led by a magistrate is currently under way.

A lot of restrictions have since been eased - but fear, mistrust and a deep sense of foreboding still grip Leh.

With its soaring mountains and lakes, Ladakh has long been a major draw for visitors

Authorities have asked people to stay vigilant against "the anti-social and anti-national elements attempting to disturb harmony", further souring sentiments among the locals.

Political and defence experts have expressed caution, saying any escalation would only alienate people, posing serious risks for India's national security.

"Ladakh is a highly sensitive region, sharing borders with both of India's rivals - China and Pakistan. We need to make sure that this area remains stable," says Lt Gen Deependra Singh Hooda, who headed the Indian army's Northern Command from 2012-2016.

The region was the site of deadly border clashes between India and China in 2020, and also includes Kargil, where India and Pakistan fought a short war in 1999.

"Ladakhis have traditionally supported the army but narratives branding them anti-nationals could change things," said Lt Gen Hooda.

But for some, reconciliation may no longer be an option.

Several protesters the BBC spoke to said they do not support "violence in any form and would continue to oppose it".

But what happened, they add, cannot be ignored either. "People have all kinds of romanticised ideas about Ladakh. But beyond the beauty, the region is a complex patchwork of cultures and identities, each with its own unique history," said Jigna.

Activist Sonam Wangchuk has been accused of instigating violence - a charge he denies

Ladakh's 300,000 people are almost equally made up of Muslims and Buddhists. The Leh region is dominated by Buddhists - predominantly tribespeople - while Kargil is inhabited by Muslims.

Historically, the Buddhist community has demanded a separate region for its people, and those in Kargil have wanted to be integrated with Muslim-majority Indian-administered Kashmir.

In 2019, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government revoked Article 370 of the constitution which accorded special status, including land and job rights, to the former state of Jammu and Kashmir, residents in Ladakh were initially jubilant.

They hoped the decision would allow them more autonomy in their culture and spur economic development in the remote region. But as time passed, many began to feel disillusioned saying the benefits never reached them.

Residents like Deskit Angmo say promises were broken and locals feel cheated

With the special status gone, the autonomy of hill councils - that were formed in the 1990s to give residents a greater say in local politics - began to wane. The changes also allowed non-residents to buy land and property in the region.

People who once supported the government now accused it of throwing open the region to "industrialists and capitalists" and making them vulnerable to demographic changes.

"We felt cheated. We were promised that our land, jobs and cultural identity will be protected but this was a lie," said Diskit Gangjor, secretary of the women's wing of the Ladakh Buddhist Association (LBA), an organisation leading the protests.

As anger grew, residents from Kargil and Leh joined hands and sought full statehood for their region.

The government has rushed in extra paramilitary troops into the region after the violence

Other demands included adding Ladakh to a list, known as the Sixth Schedule, that guarantees protections to land and a nominal degree of autonomy to tribal areas under the constitution, along with a parliamentary seat each for Leh and Kargil districts.

Over the years, Ladakh's main advocacy groups held several rounds of talks with the federal home ministry, but failed to make any progress.

In the meantime, unemployment soared in the region, making its young people increasingly more frustrated.

It was in this context that Wangchuk and others began their protest last month.

"What happened on 24 September wasn't just about that single day. It can't be understood in isolation - you have to look at where this frustration is coming from," says Nardon Shunu, a women's rights activist.

The BBC has contacted Ladakh's director general of police and other senior officials for comment.

Since Wangchuk's arrest, the region's main civil society groups have withdrawn from dialogue with the federal government.

Protesters say that even though their most vocal leader has been detained, they will continue their struggle peacefully.

"What we are doing is not anti-national. These are our genuine demands and we will achieve our goal peacefully," Phunchok, the businessman, said.

For now, the road to peace looks uncertain.

Hundreds of soldiers have been guarding the protest site - one of Leh's main public parks - since last week. Protesters say they want to resume their movement, but don't know when that'll happen. Many of them have gone icognito fearing reprisals.

"What happened that day [on the day of clashes] felt was chaos of another level," said Phunchok. " It will take a long time to recover from it."

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, external, YouTube,, external X, external and Facebook, external.

Related topics

Read more

- Published25 September

- Published22 March 2024

- Published24 October 2024