Medieval grave slab found on seabed now on display

The two Purbeck grave slabs, from the 13th Century, are thought to be the first of their kind ever found in a shipwreck

- Published

A grave slab raised from the site of a 13th Century shipwreck has gone on display in a museum for the first time.

The Mortar Wreck, so-called for its cargo of stone tools used to grind food, was found about a mile (1.6km) off the Dorset coast in Studland Bay, Isle of Purbeck.

Tom Cousins, who led the excavation, said the site had been known for years, but was dismissed as nothing more than a pile of stones.

New surveys in 2019 and 2020 revealed a treasure trove of artefacts, which are now being exhibited in Poole museum in Dorset.

The site of the wreck had previously been dismissed by others as nothing more than a pile of quarried stones

Researchers said the discovery deepened their understanding of the stone trade in Britain and Europe.

The Mortar Wreck, dated to about 1250, is the oldest surviving English shipwreck with a surviving, visible hull, according to Historic England, and was given protected status in 2022.

Among other finds were a stone cauldron for cooking, and Irish timbers used for the hull.

Tom Cousins, who led the excavation, said the finds provided a "snapshot" of the period's seafaring culture

Mr Cousins, maritime archaeologist at Bournemouth University, said: "Our skipper said 'have you ever dived this mark?'

"We said 'no, because it's rubbish, there's nothing there'.

"When [the divers] came up, they said: 'You need to come down and see this'."

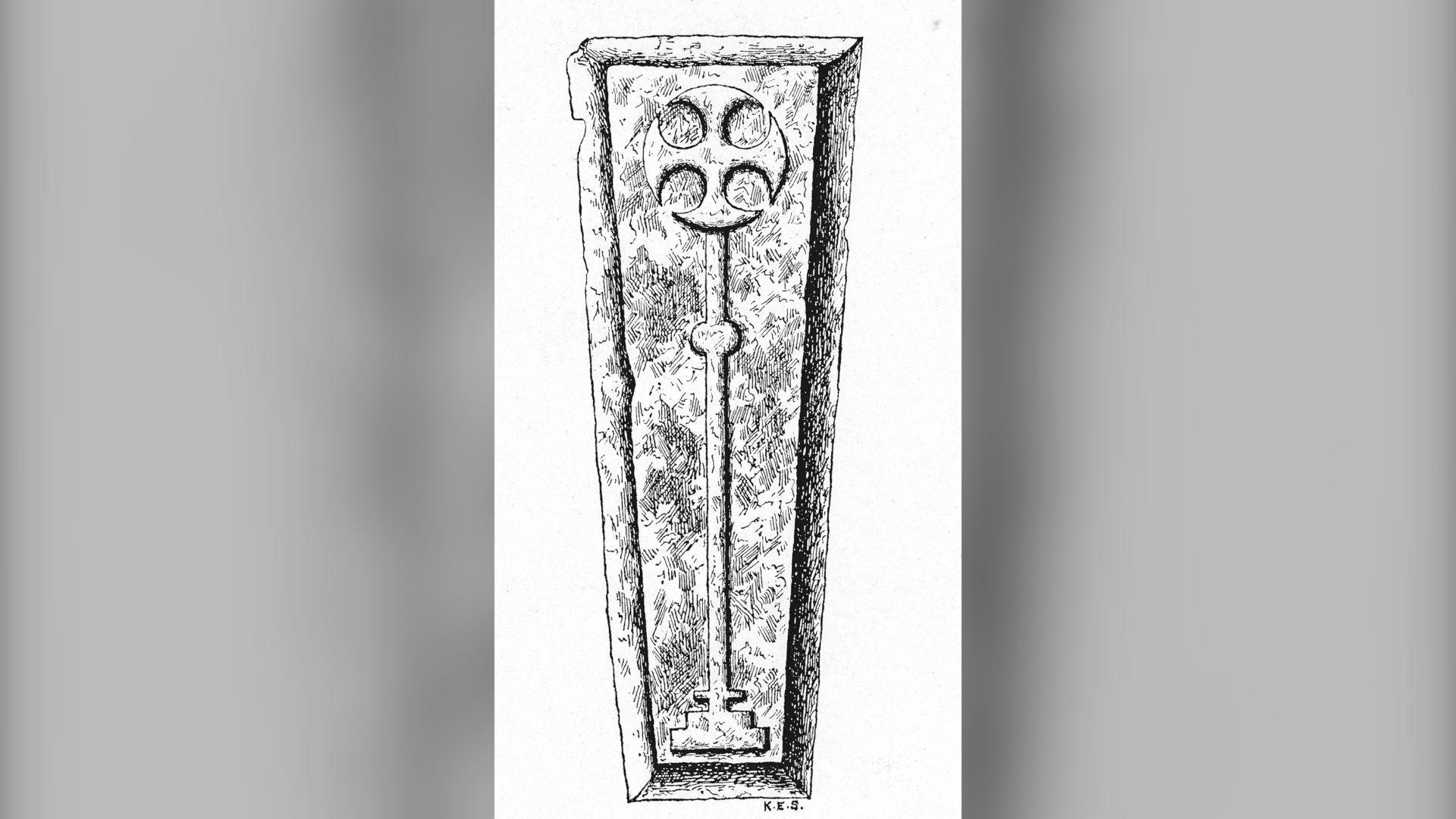

The star finds from the shipwreck were two 13th Century grave slabs of Dorset Purbeck Stone, which has been quarried on the Isle of Purbeck since at least Roman times.

It can be polished like marble and was a popular decorative building material, used in landmarks like the Tower of London and Westminster Abbey.

The stone has also been found as far afield as Denmark, according to the archaeologists.

The slab on display closely resembles that of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, who died in 1228

"The 13th Century is the heyday of the marble industry - you won't find a church or cathedral that doesn't have Purbeck marble in it," said Mr Cousins.

Most of that stone was moved around by ships - but nobody is sure why this one sank.

"It's probably been overloaded, there's a crack in the hull, there's 30 tonnes of stone on board - you can't really do anything about it," he said.

The ship itself probably looked like a "souped-up" version of a classic Viking ship, Mr Cousins said.

Marine excavations were unique, he continued, because unlike when digging on land, there are not things mixed in from other time periods.

"It's a small snapshot in time," he said. "We can start reconstructing the culture, the environment."

Collections officer at Poole Museum Joe Raine called the slab a "real showstopper"

The researchers said they hoped the slabs would be stepping stones in and helping them understand the massive stone trade of the period.

The collections officer for Poole Museum, Joe Raine, called the exhibition "a real showstopper."

The finds will be placed alongside other maritime finds like those from the Swash Channel wreck, a 17th Century merchant ship that sank near Poole Harbour.

"You can't help getting sucked in," said Mr Raine. "Hopefully [visitors] start to see a little of themselves in those people from 800 years ago."

Related topics

- Published6 June 2024

- Published20 July 2022

- Published21 July 2022