How achievable is Reform's plan on migration?

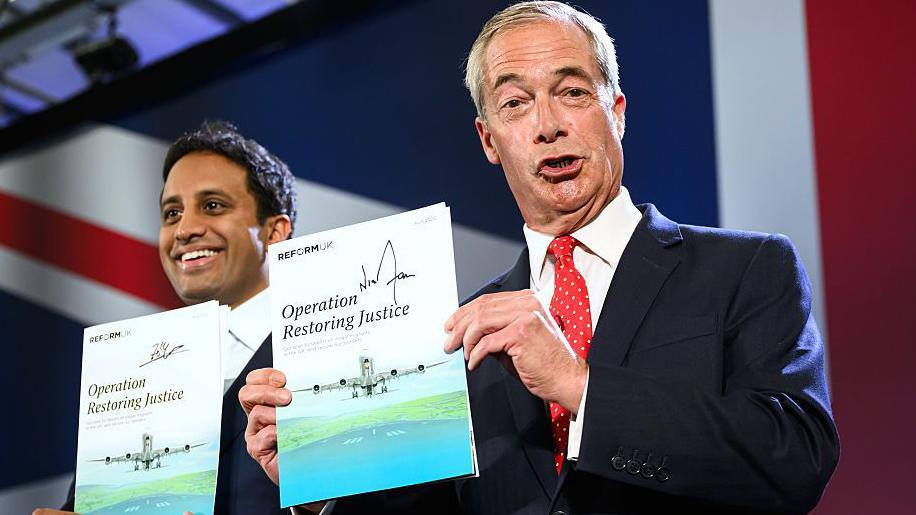

Reform UK leader Nigel Farage (R) and chair Zia Yusuf following the party's new policy

- Published

Nigel Farage has set out how a Reform government would tackle what he called "uncontrolled illegal migration" – with moves including human rights law changes, and mass deportations. But how deliverable are the plans?

Let's start with the headline figure of how many people the party badges as illegal migrants (the precise definition of this is up for debate) that it says it will deport.

There's no figure in the party's document - but during the event Nigel Farage asked Reform UK chair Zia Yusuf whether it was realistic to deport 500,000-600,000 people within the lifetime of the first Parliament under a Reform UK government, to which he replied "totally, yeah".

The party is proposing to create secure facilities to hold 24,000 to be deported every month - that gives us another figure of 288,000 a year, ramping up after 18 months of building work.

Removing 6,000 people per week would, using today's operations as a guide, require an average of 1.7 escorting officers per individual removed. When you break that down into departing planes per day, that's within the maths for the party's projection of five flights per day.

But these targets are far in excess of what any government has ever achieved. An average of 158 people per flight, plus security, would require the equivalent of five jumbo jets to be available all year around. That per flight number of 158 is three times higher that the numbers currently removed on the most-packed departures.

Nobody knows how many people are in the UK without permission or where they are. Evidence shows many of them are in vulnerable situations, including in what amounts to modern day slavery.

Reform thinks it can find them with "cutting edge data fusion" and says it would give the state access to a vast range of personal information that it currently cannot obtain without a good reason.

Any "police encounter" would involve "mandatory biometric capture", the party document says, which could go far beyond anything that officers can currently do without first arresting you.

Reform hopes this information will more quickly identify candidates for removal - but the wide scope of the plan could conflict with the UK's tough data protection and privacy laws.

There is also a warning from history, with the government paying out more than £105m in compensation to thousands of people and their families who were caught up in the Windrush scandal.

What would such a scheme cost?

No government has ever tried to build prison-like detention facilities for 24,000 people in 18 months - the time scales envisaged by Reform - or at the cost claimed.

For detention facilities to be escape-proof, they have to be the equivalent of what's known as a "Category B" prison - which means there are walls and locked doors, wings and gates everywhere with a suitable level of staffing.

Official figures from the current prison programme show that it costs about £500,000 per bed to build such "closed" facilities - and that's broadly the design standard used for immigration removal centres too.

That means that if the party in government were to build 24,000 new detention spaces to that standard, it would cost about £12bn.

Reform says it will build them for less by creating "modular accommodation" in remote parts of the UK. There are three immediate questions. First, would a modular plan meet the security standards? Second, where would they be built? Thirdly, how would they deal with local planning concerns which have repeatedly massively delayed prison building schemes in the UK?

New laws could make scheme possible

Boris Johnson's government promised 20,000 new prison spaces - but over five years only opened one new prison - partly because of planning disputes.

The plan involves creating new laws to fast-track people into detention and removal from the UK - and providing the legislation is correctly worded, there is nothing in principle to say that Parliament could not create such a scheme.

But it has been tried before and failed. In 2010 and then in 2015 judges ruled that accelerating failed asylum seekers through to removal was unlawful.

The courts found in 2015 that fast-tracking conflicted with one of the UK's basic legal principles: the opportunity to fairly put your case before a court rules against you.

So the challenge for Reform is how they deal with the fact that everyone has a right to be heard. One approach would be to say that it does not apply to immigration cases. That would inevitably faced sustained challenge on constitutional principles all the way up to the Supreme Court.

Who knows if a carefully worded new law could see that off. But the fact is that good law takes time to write - and Reform would also have to unpick a lot of other laws too.

That takes Parliamentary time to get right. Labour's current plan to "smash the gangs" by creating new counter-terrorism style powers to target people smugglers can't be said to be working or not yet because it is still being debated by Parliament.

Assuming Reform's plan is bigger than that, experience shows that new laws of this magnitude can take at least a year to become a reality.

A new government could, with a mandate and healthy majority, try to push it through faster - but policy advisers in Whitehall would warn ministers that rushing the job means a bad job that could later become unworkable.

Reform prepared to deport 600,000 under migration plans

- Published26 August

How Reform has changed the debate on migration

- Published26 August

Farage vows mass deportations to tackle small boats

- Published23 August

Pulling out of the ECHR?

Part of Reform's argument that it will do more because it will pull out of three treaties including the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the UN Convention Against Torture.

A Reform government could indeed do so - although it would lead to some thorny legal problems if a lot of other laws linked to both were not unpicked at the same time.

But it's not clear whether such moves would really do as much as Farage suggested.

The ECHR is not, for instance, a bar on removing someone from the UK - and there is appetite among some European governments to tinker with it.

As for the UN convention on torture, that kind of abuse has been outlawed in the UK, by our own laws, since 1640.

If the UK pulled out of treaties, the risk is that our government loses international influence that it has built up over decades.

There are two specific consequences of leaving the ECHR.

Doing so would breach clearly written guarantees in Northern Ireland's 1998 Good Friday agreement which have been the bedrock of peace and prosperity there since 1998.

A Reform government could argue that its proposed Bill of Rights would do the same job - but that would be a tough sell to NI's nationalist community and to Dublin, the co-sponsor and guarantor of the political settlement that largely ended the violence.

Separately, there is the question of trade and co-operation with all our nearest neighbours in the EU.

The Brexit deal signed by the UK and EU member states says both remain under an "obligation to respect fundamental rights and legal principles as reflected, in particular, in the European Convention on Human Rights".

How would the EU react? Would there be an economic consequence, even if that had not been the intention?

Incentives to leave

One of the side-ideas in the plan is to pay people up to £2,500 to leave the UK voluntarily. This is not new and the current scheme saves the government huge sums because paying people to go is cheaper than using the courts. Reform's offer is less than the £3,000 currently on offer.

In the year ending June 2025, 26,761 people took up a deal to voluntarily leave the UK. That's 13% up on the previous year and approaching record levels of more than 30,000 returns, seen between 2010 and 2014.

Finally, there is the question of £2bn to persuade other countries into returns deals. It's difficult to know how far that cash will travel. Would there be one-off payments or would a government get an annual performance-related pay-out? Rwanda's ministers proved to be such good negotiators they squeezed the UK's wallet for £700m - and received nobody in return.

And who would the UK be prepared to hand cash to? Would a Reform government give British taxpayer's money to the Taliban regime with its dire record of the treatment of women? How would such payments work given the UK is a key player in the international sanctions that target its leaders?

- Published22 October

- Published20 August