'My heart bursts to think of parting with you'

By 1954 about 27,000 children had grown up in the Foundling Hospital

- Published

Paper hearts, scraps of fabric and faded ribbons are some of the mementos that weave together the stories of abandoned babies and children who were taken in by the Bloomsbury Foundling Hospital.

The notes and tokens were part of the admission process at the central London institution, which looked after about 27,000 children who had been abandoned or whose parents were unable to look after them since its inception in 1739 by seafarer and philanthropist Thomas Coram.

For the first time, about 100,000 documents are available for free to the public as they have been uploaded to an online database, external by the charity Coram, which continues the hospital's work.

There are some handwritten notes, such as this one from 1823: “My dear dear child, my heart is ready to burst at the thoughts of parting with you but alas necessity obliges me as you are deserted by your unnatural father; oh my dear it is impossible to express how wretched I feel.”

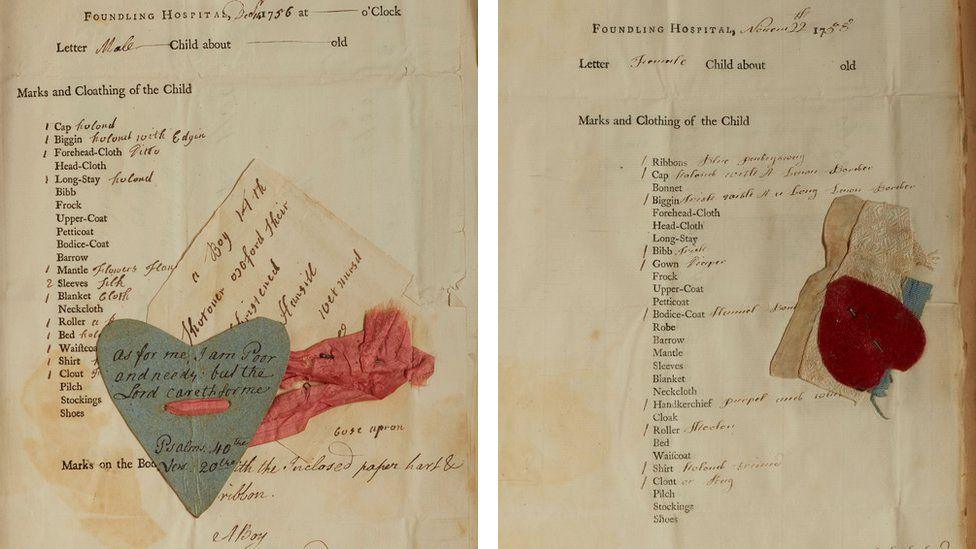

Two documents from the online archive show inventories for abandoned children, together with paper hearts featuring messages from their mothers

The hospital, which effectively operated as a children’s home, looked after boys until they were old enough to work on merchant ships or join the military, and girls until they were old enough to begin service jobs.

The admission bundles can now be seen as part of the database. A new exhibition, Echoes of Care, has also been created at its offices in Bloomsbury.

The documents hint at the stories of young women forced to abandon their children; those who had given birth out of wedlock, or who had to choose between leaving their child and entering the workhouse, or who had themselves been abandoned by husbands or family.

One mother wrote on her token in 1756: “As for me, I am poor and needy but the Lord careth for me."

The tokens were not about sentimentality: they were used as identification for the tiny proportion - about 3% - of the children who were reclaimed.

Each one that remains in the archive represents a child who was never reunited with their birth family.

The Founding Hospital was established in 1739 by seafarer and philanthropist Thomas Coram

On the day a child was admitted to the hospital, staff filled out a billet with their sex and birth date, whether they had been christened, an inventory of clothes, and a number.

Receipts were issued to the mother, with the instruction to keep it in case she needed it to get her son or daughter back.

The billet did not record the child’s original name. They were given a new one.

The billet sheet was folded around any tokens - a ribbon, a rosette, a button or a coin - sealing it within a little package.

If the child was ever claimed, the billet would be opened and the token used as a method of confirming the identity of the child by either describing the token or producing a matching part of it.

The children who were not claimed never learned if a token had been left for them.

A painting from 1858 depicts a rare reunion, with the mother dropping her receipt for her child in the emotion of the moment

Few mothers were reunited with their children, despite records showing a large number of inquiries from mothers about their child’s welfare.

The process had strict rules and the mother had to specify why they believed she could now care for her child.

For example, an Elizabeth Steele was only able to claim her daughter after she came into a large sum of money following her father’s death.

Some mothers received only a death certificate in reply because the child had died in the interim; and some never completed the process.

The hospital continued to take in children until 1935, when it was relocated to Berkhamsted in Hertfordshire, where it functioned as a residential home until 1954.

Exercise and play were a key part of life at the home

The home's ethos was described as involving a "commitment to health, sport, and play”.

Records show that as far back as 1746, children were encouraged to exercise on Saturdays to "increase their strength, activity and hardiness”.

Eleanor Allen became a pupil at the Berkhamsted home during World War Two after her mother, who was 19, had a relationship with a 33-year-old man who abandoned her and went back to his wife.

“By the time I was born in the Mile End Hospital in east London my mother had applied to the Foundling Hospital to admit me,” she says.

“I was accepted into the hospital’s care and placed with a foster mother. At the age of four I was moved to live at the Foundling Hospital in Berkhamsted.”

Eleanor later discovered her mother was pregnant again and went on to marry the father of her half-sisters.

When she was in her 60s, the Coram charity helped her meet her three half-siblings.

The hospital continued to take in children until 1935, when it was relocated to Berkhamsted in Hertfordshire (picture from 1931)

John Caldicott's mother was pregnant with him when she was 27 years old.

After a few months she lost her job at a laundry and found herself on the street, with nowhere to go and no support from her family.

The mother appealed for him to be admitted to the Foundling Hospital, as her only other alternative would have been to go to the workhouse.

Like Eleanor, he was taken in by a foster family until the age of five, which was the normal procedure before children were moved to the hospital.

“On a typical day we used to get up early and go into the washrooms, dress in the Foundling Hospital uniform, line up in twos, and [were] taken down to the dining hall for breakfast - and then play outside until lessons started," he says.

William Hogarth's engraving Several children of the Foundling Hospital, 1739, depicts founder Captain Thomas Coram approaching

“It had to be really bad weather for us not to go outside. I can remember when, in 1947, the weather was awful, and we had to huddle to keep warm under the colonnades.”

He says he often found life at the hospital difficult with "bullying by older boys, a sense of loneliness and the social stigma of associated with being an illegitimate child".

But he also says it made him “extraordinarily independent", and gave him the discipline and drive to succeed.

By 1954, 27,000 children had grown up in the Foundling Hospital.

A depiction of Coram outside the Foundling Hospital

Dr Carol Homden, the head of Coram, said the documents provided "a new opportunity to research this fascinating chapter in our history as the first and longest-continuing children’s charity".

“[They’re] rare accounts of the issues faced by women who had no source of support in the harsh environment before the welfare state.”

Today, Coram supports hundreds of thousands of children, young people and families with free legal advice, adoption support and advocacy.

Echoes of Care: The Living History of Coram and the Foundling Hospital is free and can be seen at Coram, 41 Brunswick Square, until March 2025

All images from Coram are subject to copyright

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external