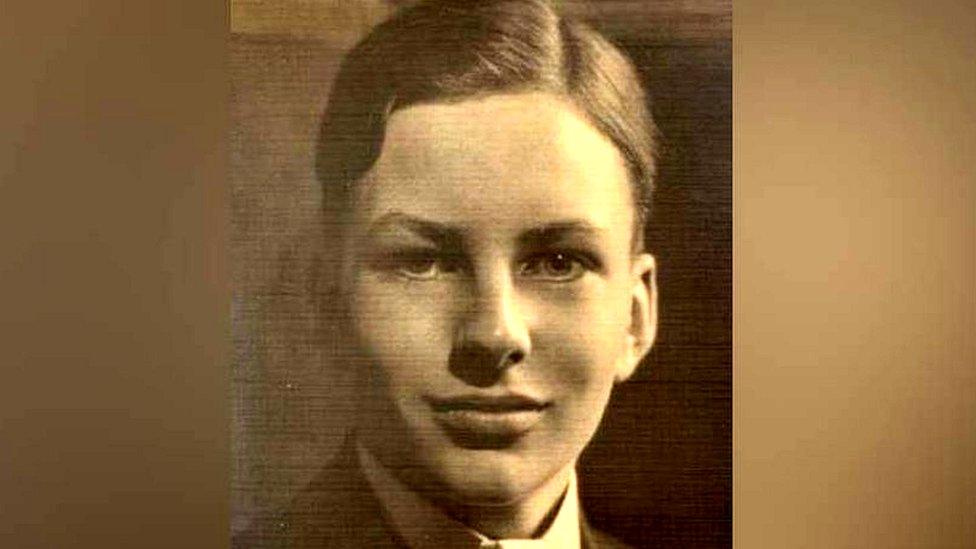

Book tells how city on Nazi hitlist coped in war

Wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill on a morale-raising visit to a bombed Swansea in April 1941

- Published

As people gather at war memorials across Swansea for Remembrance events, many thoughts will be on the devastating three-night blitz of February 1941.

As devastating as that bombing was, the story of the Swansea home front - or how civilians cope during war - is much more diverse.

In a new account, author and local historian Bernard Lewis aims to provide a wider perspective on the city's World War Two experience.

The book - Swansea and the Second World War - says while the bombing and the response were similar to other towns and cities such as Coventry, Liverpool, Plymouth and London, several factors made it different, from the 1930s to the 1950s.

Childhood memories of 'bombing horror', 80 years on

- Published19 February 2021

City unveils digital Blitz archive for anniversary

- Published16 February 2021

Thousands of World War Two bombs left unexploded

- Published27 December 2022

They centre around the area's mix of industry, demographics and geography.

Mr Lewis said: "Swansea suffered no more and no less than lots of places across the UK, but the way in which it impacted us is different.

"That's why I believe we need to talk about the concentration of industry here, the relatively small population, and the beautiful but dangerous landscape."

The blitz between 19 - 21 February 1941 killed more than 200 of the 384 people who would die in 40 Luftwaffe air raids over Swansea throughout the war.

In that short space bombers dropped 1,273 high explosives and more than 56,000 incendiary devices over some 40 acres, demolishing what had been the town centre: a higher concentration than on any British conurbation outside London.

However, the story starts well before that.

Swansea's industry

A Swansea Home Guard unit during a training exercise

As early as the late 1930s, even as then Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was declaring "peace in our time", plans were afoot for Swansea's defence.

With the concentration of heavy industry in such a small area, the region was always near the top of the Nazis' list of targets.

Mr Lewis explains: "Within a 10-mile radius you have the docks, copper works, iron and steel, coal transport, and the oil refinery at Llandarcy.

"In 1938 the Swansea town clerk, Howell L Lang-Coath, was appointed as air raid precautions controller and he started to build up the civil defence services that would be needed in a time of war."

Swansea demographics

But with a population of just a quarter of a million, Swansea lacked the labour force for such a defensive effort.

Mr Lewis said: "Other towns and cities had it far worse, but they had greater populations to fill the roles, and were spread out over a much bigger area; some parts of London were hardly touched by the [capital's own] blitz, and must have wondered if there was actually a war going on at all.

"Whereas in Swansea the simple act of responding to the disaster necessitated enrolling 2.5% of the community, and that's before you consider men who'd gone away to fight, and those who were too old or young or infirm to take part."

Another strain was the government's decision to intern Italian immigrants as foreign aliens when Mussolini joined the war.

"Italians had settled in Swansea from the mid to late 19th Century onwards, and had generally assimilated into Swansea society incredibly well.

"However, with the hysteria of war, many of the shops and cafes they ran were looted and had their windows broken.

"This was not only terrifying for the Italian families who believed they were part of the Welsh community, it also put a further strain on the whole Swansea economy and infrastructure as the businesses they ran were precisely the ones who were helping to administer rationing and keep food coming."

Ben Evans department store - Swansea's premier shopping destination, was burnt out during the attacks of February 1941

While Swansea desperately needed adult migrant labour such as had flowed into London, what they actually got was an influx of children from other bombed-out cities across the UK and as part of the Jewish kindertransport which rescued youngsters from the European mainland.

"These youngsters obviously needed people to care for them - as foster parents and teachers - and that further diminished the labour pool who could contribute to the war effort," said Mr Lewis.

By 1941 Swansea was dependent on women and very old and young men to keep the system running.

At the height of the crisis it was said that the Home Guard could only issue one rifle between three recruits, and many went on patrol with clubs and pitchforks.

In 1943 the town experienced a new stress, with the arrival of the US Army’s 2nd Infantry Division.

"There was a lot of resentment from local men; in common with the rest of the UK, 'the Yanks' were seen as 'overpaid, oversexed and over here'."

"Outbreaks of violence weren't uncommon between the two groups, but I've been able to find at least a hundred marriages between GIs and Swansea girls, including the great-grandparents of Welsh footballer Joe Rodon."

Swansea's geography

Unlike the sprawling factories of Birmingham or Manchester, Swansea's geography meant population and industry were hemmed into a concentrated area, with the sea to its south and a ring of hills to the north and west.

"You've got Kilvey Hill behind you, which acted both as a target for bombers, and a sort of funnel which maximised the damage.

"If the bombers drop anything short of Kilvey Hill after coming off the seaward side, it would either hit the docks and the town, or else cause a firestorm which would roll down from the higher ground. In that horseshoe you have very densely packed inhabitants, which greatly increased the risk of injury and death."

Mr Lewis also believes the expanse of beaches along the coastline made the region a credible, if not a likely target for a German invasion.

In response over 100 pillboxes were constructed, though no sooner were they completed than the threat of an amphibious landing receded.

Yet perhaps the biggest geographical legacy is in Swansea's current architecture.

"Swansea is a mismatch of Victorian buildings and 1950s 'shoeboxes', thrown up after the war to replace the bombed-out sites," said Mr Lewis.

"Much of the post-war planning was ugly and cheap, but today we wear our scars proudly, and they have become part of our collective personality."

Related topics

- Published23 October 2021

- Published1 September 2024

- Published3 November 2024