BBC tracks down smuggler behind Channel crossing which killed Sara, 7

- Published

As he ambled, nonchalantly, across a sunlit public square, the smuggler appeared to have no idea he was being followed.

He was a short, stocky, 39-year-old in a pale green shell suit and baseball cap - an unremarkable figure taking an afternoon stroll from a tented migrant reception centre to a nearby tram station.

Our team broke into a run.

“We know who you are,” I said, as we caught up with him halfway across the square in Luxembourg’s capital city.

“You’re a smuggler.”

Watch: The BBC's Andrew Harding confronts the people smuggler nicknamed Jabal - “The Mountain” in Arabic

It was a confrontation that marked the culmination of a BBC investigation that had begun 51 days earlier - hours after five people, including a seven-year-old girl named Sara, had died in the sea off northern France. She had suffocated beneath a crush of bodies inside an inflatable boat.

That investigation had taken us from the informal migrant camps around Calais and Boulogne, to a French police unit in Lille, to a market town in Essex, to the Belgian port of Antwerp, Berlin, and finally to Luxembourg and a three-day stakeout at the gates of the country’s migrant reception centre.

The man now facing us - eyes narrowed, shoulders and hands raised in a half-shrug - was, we knew for sure, the smuggler who had been paid to organise Sara and her family’s dangerous voyage to England.

This is the story of how we tracked him down.

“I swear it’s not me,” the smuggler declared, repeatedly, backing towards a nearby tram station beside Luxembourg’s European Court of Justice.

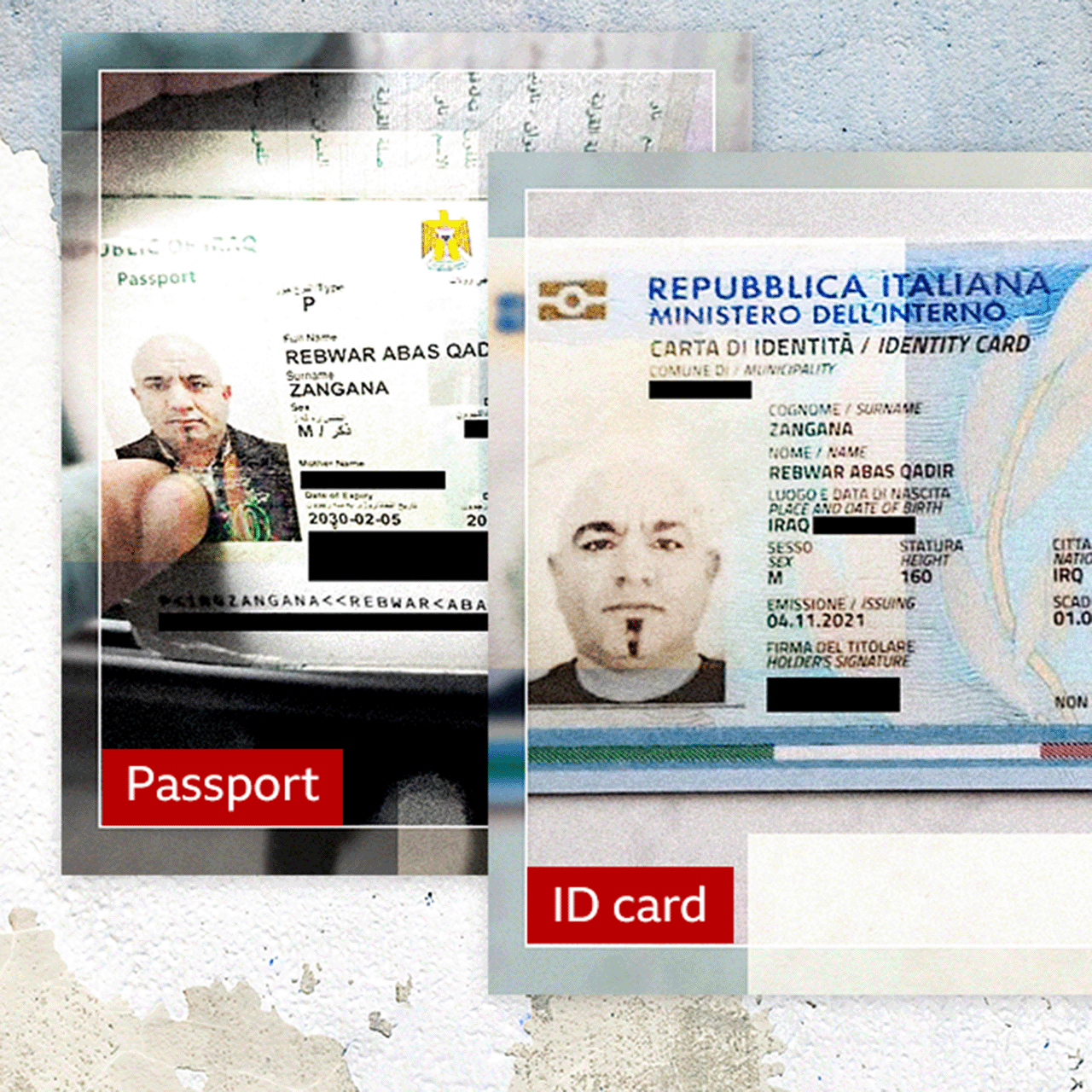

But we had already seen his Iraqi passport and an Italian identity card. Moments after we began to confront him, a final piece of the jigsaw slotted into place, when his phone began ringing in his pocket.

At first, he ignored it, but when he finally pulled it out and we saw the incoming call number on his screen, we had conclusive proof of his guilt.

Why? Because we were the ones ringing him.

In the previous weeks, a member of our BBC team had been posing as a migrant seeking to cross the Channel to England. After reaching out to several alleged middlemen working within the smuggler’s wider network, our colleague, “Mahmoud”, had finally been put in direct contact with him.

We had then secretly recorded several phone conversations with the smuggler - speaking to him on the same phone he was now holding in his hand. In those calls he had confirmed his identity and told us he was still in the smuggling business.

For a fee, he said he could offer us “an easy journey” with “extra guards, all carrying weapons” in the next small boat leaving northern France. The current price was €1,500 (£1,269) per person.

As we stood before him now, we could see our telephone number, clearly, on his phone’s screen.

We had found our man.

Our investigation had been prompted by the experience of watching a desperate incident unfold on the French coast on 23 April.

We had been waiting, overnight, on a beach outside the resort town of Wimereux - a place we knew was a favourite launch site.

Watch on iPlayer

Calais Migrant Crisis: Andrew Harding

- Attribution

Watch: BBC witnesses boarding of boat which left five dead

We had filmed as a group of French police had sought to intercept a boat, clashing violently with two groups of smugglers and their passengers.

The police failed to stop them from boarding and we watched the chaos as the two separate passenger groups battled for space on the dangerously overcrowded inflatable. Smugglers routinely pack more than 60 people on to such boats, but this one had more than 100.

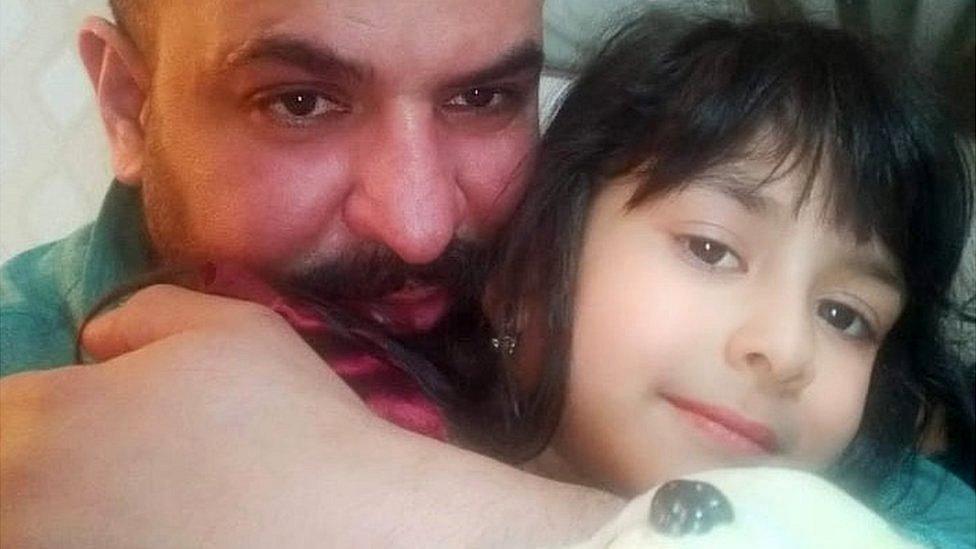

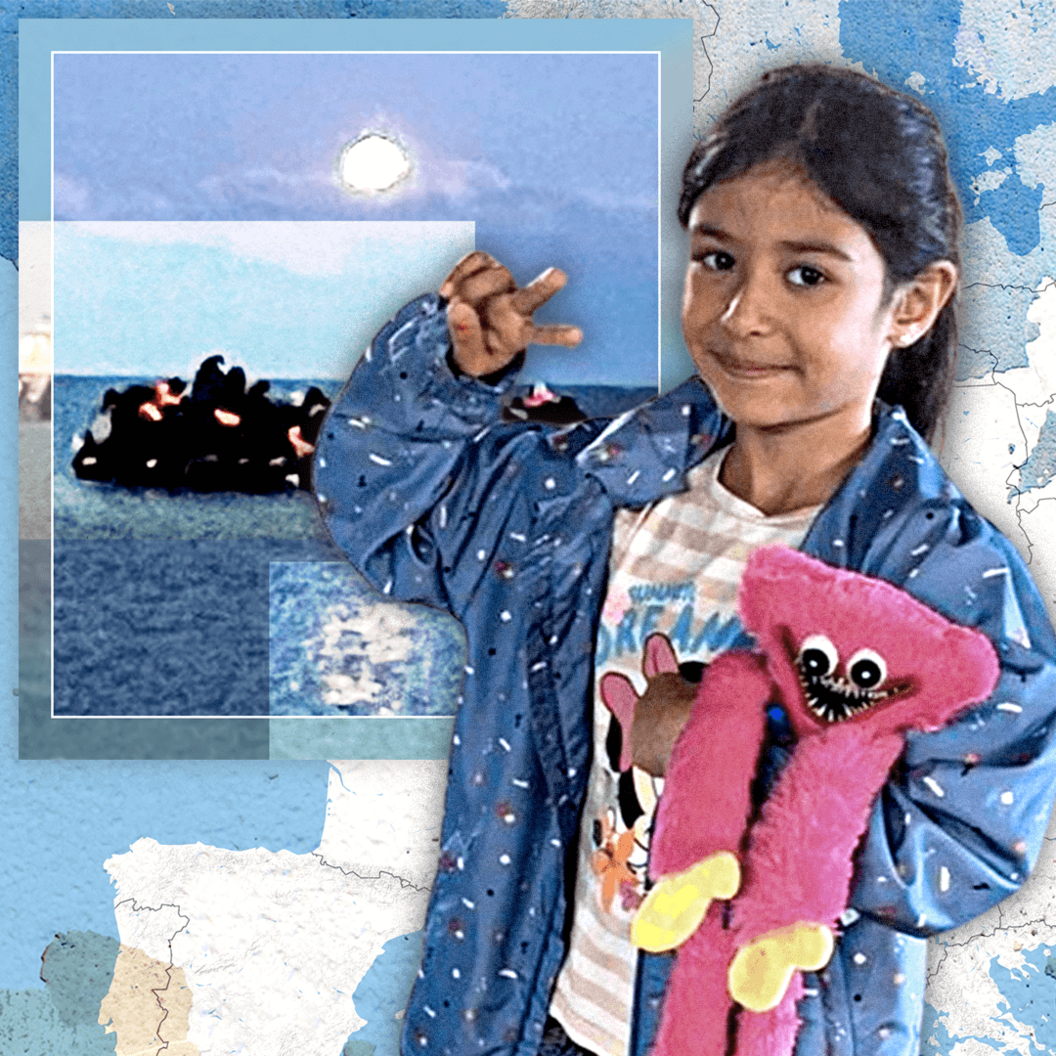

A small girl in a pink jacket - later identified as Sara - was briefly visible on her father’s shoulders.

Minutes later, a few dozen metres from the shore, she and four others were dead.

Sara had been living with family in Sweden, but they had been told they would have to leave

Some survivors, and the bodies of the dead, were taken back to shore by French rescuers - but the boat, with dozens of people still onboard, eventually continued on to England.

It was the second fatal small boat incident of the year near Wimereux. We had now reported on both.

In the days that followed, we found Sara’s family and spoke to her father Ahmed about his grief, about the guilt he and his wife felt for putting their three children at such risk, and about the fear of imminent deportation from Europe that drove his decision to attempt a crossing to the UK.

After fleeing from Iraq 14 years earlier, Ahmed’s asylum claim in Belgium had been repeatedly rejected on the grounds that his hometown of Basra was now classified as a safe area. He had recently been warned he could be deported from Belgium within days. His children - all born in Europe - had grown up living with relatives in Sweden, but had also just been given a final order to leave the country.

But we also wanted to dig deeper, to find the specific criminal gangs responsible for that boat, and to understand how they fitted into a larger, lucrative network that continued to funnel tens of thousands of migrants towards a small stretch of French coastline.

On 18 June, 15 small boats brought 882 people across the Channel - a record for a single day this year, which helped to edge the total number reaching the UK so far this year well over 12,000.

Following Sara’s death, the UK's National Crime Agency soon announced it had detained two suspected smugglers who are now awaiting extradition to France. But these were young men, allegedly working on the boat itself. Not the powerful bosses in charge behind the scenes.

Watch: “I could not protect her. I will never forgive myself”

We set out to find and speak to as many survivors from that April night as possible, meeting some in the informal migrant camps or hostels for asylum seekers near the coast in France. Most of them asked us not to use their names, not least because some were planning to make further attempts at crossing the Channel.

A young Kuwaiti man, who had been next to Sara as she died and had phoned the French police to ask for help, successfully made it to the UK a few weeks later. We tracked him down to Essex.

Many of the dozens of people who boarded the boat with Sara and her family knew nothing about those in charge of the operation. They had spoken only to relatively junior middlemen who can often be found outside the train stations in Calais or Boulogne, looking for potential clients.

Once a price had been agreed - and there was seldom much haggling - most people then went on to deposit funds electronically with intermediaries. They told us these were usually trusted businessmen, sometimes operating from barber's shops or grocery stores in places like Turkey, Paris or London. The middlemen would then pass the money on to the smuggling gang immediately after a successful crossing.

But three people - including two who had been on the same boat as Sara - told us the smuggling gang they had dealt with was operating out of the Belgian port of Antwerp, a city known for its criminal networks and illegal drugs trade. They also agreed that the gang was led by a man nicknamed Jabal - “The Mountain” in Arabic. Two of them had met Jabal in person. One had spoken by phone.

The trail also took us further east to Berlin, where another source confirmed Jabal’s identity and told us he had promised him a second crossing attempt, after a first one had gone wrong.

All our sources, by this point, were telling us that The Mountain was in Belgium, probably Antwerp.

We arrived in Antwerp in May and began working on a plan to locate and confront The Mountain. One of his previous clients had shared a photograph, and another source had provided us with a copy of his Iraqi passport and a European identity card that appeared to have been issued in 2021 in a remote Italian hill town where investigations are under way into organised crime.

We discovered that The Mountain’s real name was Rebwar Abas Zangana, a Kurdish man from northern Iraq. Unmarried. Apparently a devout Muslim. A migrant himself - with an unclear immigration status - who was known to have been living recently in Calais, Brussels, and Antwerp. We were told he worked with two partners and that there might be an even more senior figure back in Iraq.

Mahmoud - our Arabic-speaking colleague posing as a migrant seeking a route to the UK - met a middleman in a barber’s shop in Antwerp, who confirmed that he knew The Mountain and would arrange for him to call us.

We waited nearly two weeks for that call, but eventually, late one night, our phone rang.

“Hello. So you want to get to Britain? How many seats do you need? Are you ready?”

The Mountain spoke in short, curt sentences. On that call, and two subsequent phone conversations, he confirmed that he was still very much in business, assuring us that the trip across the Channel was “a safe job”, and that he had refined his tactics since Sara’s death.

“How many of you are ready?” he asked, adding that the weather in Calais wasn’t good enough for a crossing the next day.

But hours after that first call to us, we learned from a source that The Mountain had recently left Antwerp in a hurry. The implication was that he feared arrest for his role in the five deaths in April. The Mountain was on the run.

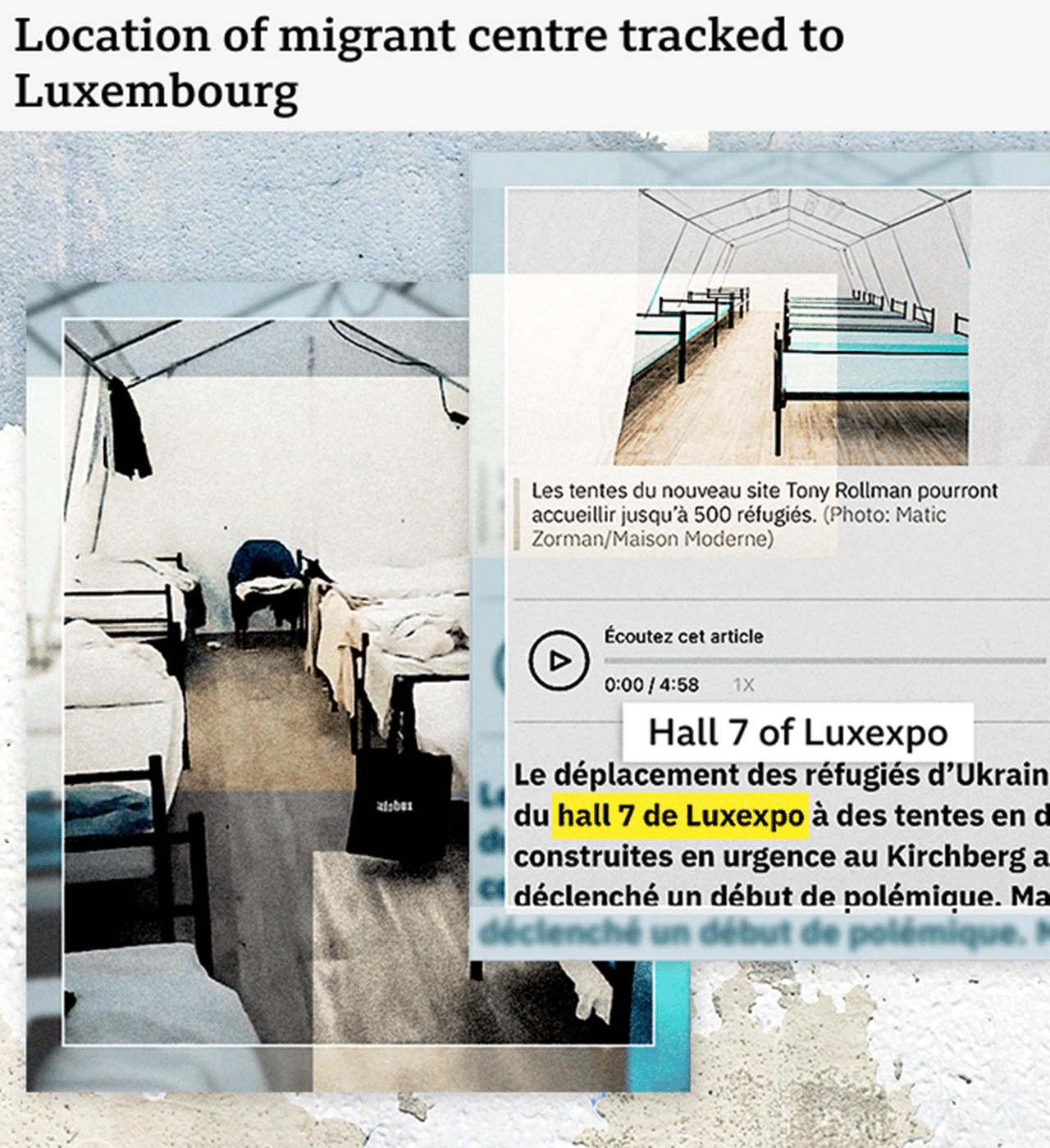

Our source then shared a screen grab from The Mountain’s phone. It was taken inside a large, white tent with rows of black beds, the sort of thing you might see in a refugee camp. When we searched on the internet for similar images, we quickly found a single and very close match, in a 2022 article about a new official refugee and migrant reception centre in Luxembourg.

We drove there immediately.

Luxembourg is a small country. Its primary reception centre for refugees and migrants is in the capital’s modern administrative centre. Why would The Mountain come here? Perhaps he simply hoped to lie low for a while, or to apply for asylum under a new name.

But how to be sure he was even here? We couldn’t simply wander in. The compound was closed to the general public, with a single entry/exit point guarded by at least four private security guards.

The BBC spent three days monitoring the centre from a higher vantage point

That first evening in Luxembourg, again posing as a migrant called Mahmoud, our colleague managed to speak to The Mountain by phone. In a co-ordinated move, another BBC colleague drove around the periphery of the compound at the same time, sounding the car’s horn at regular intervals. Listening in on the conversation, we could clearly hear the beeping coming through the smuggler’s phone.

The Mountain was here.

But how to lure him out without causing suspicion? If he fled again and we missed him, we would be back to square one.

The only option was a stakeout.

And so, for three days, our team kept watch, monitoring the compound’s entrance, and peering from a higher vantage point that overlooked the centre, giving us a view inside.

Finally, at just before 15:00 on the third day, we spotted The Mountain walking out with a group of other migrants. He turned left, heading towards the tram station. We broke into a run.

After the confrontation, we informed the French and British police about our findings

“It’s not me, brother. I don’t know anything. What’s your problem?” he said, as we caught up with him.

He looked anxious, but kept his voice low and non-confrontational as he backed towards the tram station.

I took out a picture of Sara, and asked him if he was to blame for the seven-year-old’s death. He shook his head again.

And then we rang his phone number. He could have ignored it. He could have waited in silence until a tram arrived. But when we asked him to answer his phone, and to show it to us, he seemed momentarily confused and did as we requested.

Leaning closer, we saw the screen and saw the phone number we had been using to call him for days to organise a small boat trip to the UK.

There could be no doubt about his identity.

The smugglers are greedy and should face justice, says Sara's father Ahmed

In the aftermath of our confrontation, we told the French police - who are leading the investigation into the deaths in April - about our findings. They said they would not be commenting at this stage.

The UK is spending half a billion pounds over three years to support efforts by French police to secure its coastline and to track and disrupt the people smuggling networks across Europe.

But the French border police told us they were deeply alarmed by the growing violence of the smugglers, and - while claiming some success in arresting gang leaders - senior French officials have privately suggested that a long-term solution will depend on the UK changing its own immigration and labour policies.

Sara's surviving family are living in a temporary hostel outside Lille

Today, Sara’s surviving family - her father Ahmed, mother Nour, 12-year-old sister Rahaf and nine-year-old brother, Hussam - are staying at a temporary hostel for migrants in a tiny village outside the northern French city of Lille. The children have no access to school, and no right to remain in France beyond the autumn.

“[I want] a normal life, like everybody. I’m missing out so much. I want to go to school in England because I have my cousin there. She is my age. I miss… my friends,” Rahaf told us, before sobbing.

Ahmed is in contact with the French police, who have shown him photographs of several suspected smugglers as part of their own investigation into the deaths. He has claimed in the past that hiring a smuggler was his only option. True or not, he says he has learned a hard lesson.

“These people are greedy. They care only about money. I hope they will face justice. All of them,” Ahmed said.

“My daughter’s death must not be in vain.”

Additional reporting by Kathy Long

Additional production/camera work by Paul Pradier, Marianne Baisnee, Riam El Dilati, Mohanad Hashim, Bruno Boelpaep, Xavier Vanpevenaege, Pol Reygaerts, Maarten Willems and Lea Guedj

Design by Lilly Huynh

Online production by James Percy

Related topics

Watch on iPlayer

- Attribution

- Published23 April 2024

- Published1 May 2024