Britain's 'Pompeii': UK's largest Bronze Age find

Archaeologists discovered the largest UK collection of everyday Bronze Age artefacts at Must Farm

- Published

The discovery of a burnt-out village dubbed Britain's Pompeii revealed "an amazing time capsule" that captured an everyday moment in late Bronze Age Britain.

The 3,000-year-old settlement at Must Farm quarry in Whittlesey, Cambridgeshire, burnt down less than a year after it was built, and a wealth of well-preserved artefacts were discovered.

The finds and some newly-made replicas will be exhibited at Peterborough Museum on Saturday.

From sophisticated technology and multi-tools to a far-flung trading network, what did this extraordinary excavation uncover?

Residents 'zoned' their homes

Years of post-excavation analysis revealed information on how the settlement's residents lived

The settlement had about 10 circular wooden houses and its excavation by Cambridge Archaeological Unit (CAU) between 2015 and 2016 revealed "an amazing time capsule", according to archaeologist Chris Wakefield.

It was first dubbed Peterborough's "Pompeii" by Duncan Wilson, chief executive of Historic England, which jointly funded the excavation with land owner Forterra.

The buildings had flexible floors, constructed from woven panels, and as the sudden blaze took hold, household goods were deposited directly into the silt below, preserving them for thousands of years.

Archaeologists were able to discover the ancient residents "zoned" , externalthe internal space in their homes, comparable to the rooms we have in houses today.

In one roundhouse, complete pots and wooden containers were recovered from the northwest suggesting that was the cooking area, metal tools appeared to have been stored in its eastern corner and fine textiles and bundles of fibres were found in the southeast corner, close to the light of the entranceway, which suggested this was a good place to work on those materials.

Sophisticated technology and far-flung trading contacts

Everyday objects like storage pots and tools were amongst the finds, but so were beads made from glass from Iran

The collection was made up of 200 wooden artefacts, more than 150 fibre and textile items, 128 pottery vessels and about 90 pieces of metalwork.

These included stackable pots and axes "a bit like a multi-tool, that you can swap in different axe heads", said Mr Wakefield.

"I think people have this perception that everyone was struggling to survive, that it was a horrible, nasty time to be alive, and actually looking inside these structures shows they've got a very sophisticated level of technology, " he said.

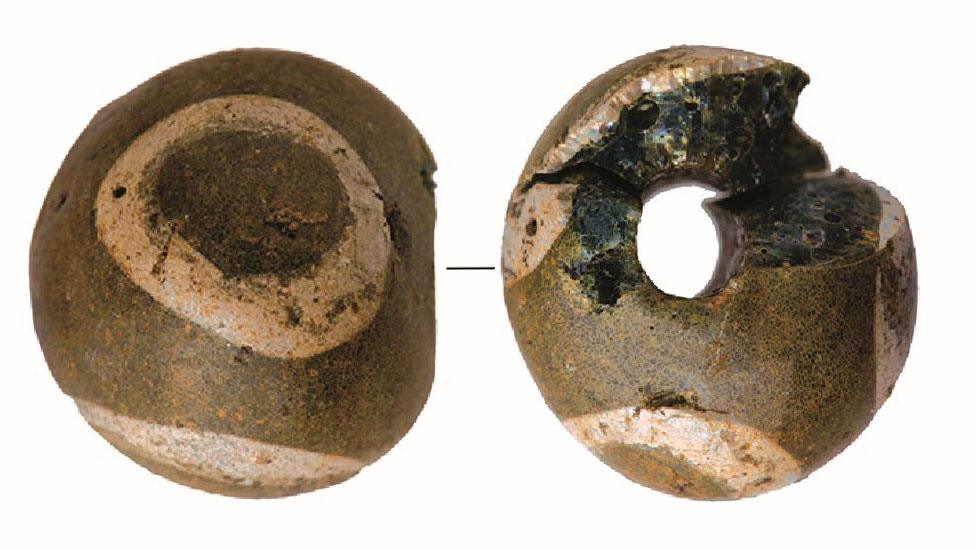

Beads from glass made thousands of miles away in Iran revealed the community's links to far-flung trading routes.

Infected with tapeworm

Human and dog faeces were analysed and parasitic worms were found

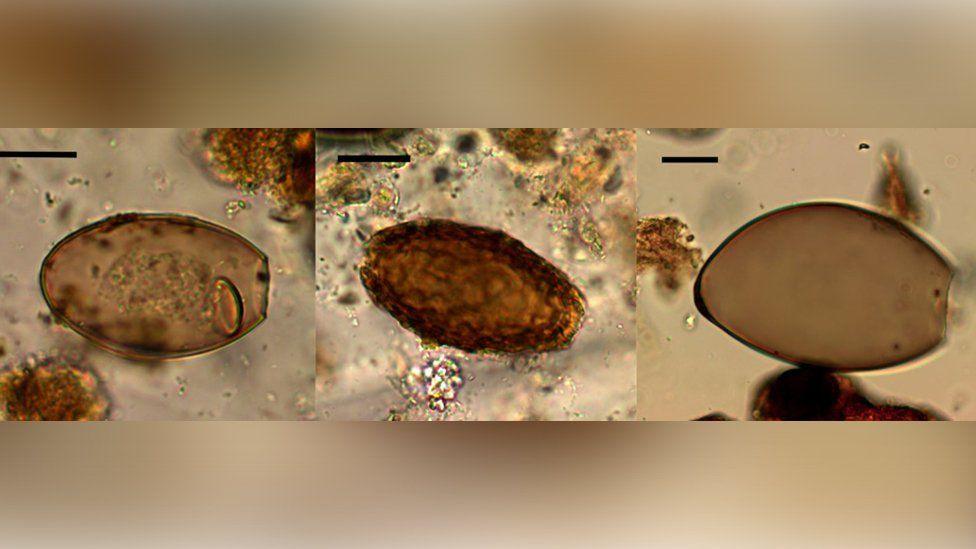

The extraordinary preservation conditions also revealed less savoury remains - pieces of human faeces or "coprolites" - which enabled scientists to discover the earliest evidence of fish tapeworm in Britain.

These can grow up to 10m (32ft) long and live coiled in the intestines.

Teams from Cambridge and Bristol universities used microscopy techniques to detect ancient parasite eggs within the faeces and determined whether it was from a human or dog.

The University of Cambridge's Dr Marissa Ledger said it also appeared they shared food with their dogs, because both were infected by similar parasitic worms from eating the raw fish, amphibians and molluscs.

The research offered the first clear understanding of prehistoric Fen people's diseases, according to the university.

'An insight into the everyday'

Replicas of many of the discoveries were commissioned and some of them will go on display at the Peterborough Museum exhibition

Experimental archaeologist, Emma Jones, said: "It's probably a reflection what a normal late Bronze Age settlement looked like, and the insight into the mundane and everyday does echo with us.

"In comparison, most archaeological findings from this era come in some sort of burial or ritual context, so relates to someone of higher status."

Ms Jones works for AncientCraft, which was commissioned to make replicas of some of the tools and jewels and she was fascinated by the recovery of 49 glass beads.

She added: "In a world that's presumed to be in browns and natural colours, because no evidence has survived of the dyeing of cloth, to see the sudden burst of colour was exciting."

Introducing Must Farm, a Bronze Age Settlement, external is at Peterborough Museum from 27 April – 28 September.

Listen to Mr Wakefield explaining more about the find on BBC Sounds.

Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp us on 0800 169 1830

Related topics

More stories like this

- Published26 April 2024

- Published27 March 2024

- Published20 March 2024

- Published9 March 2023

- Published16 August 2019

- Published12 January 2016