Engravings reveal Pepys' lifelong love of fashion

Samuel Pepys' diary (1660 to 1669) and later collections of fashion plates show that fashion trends were as important to men as women in the 17th Century

- Published

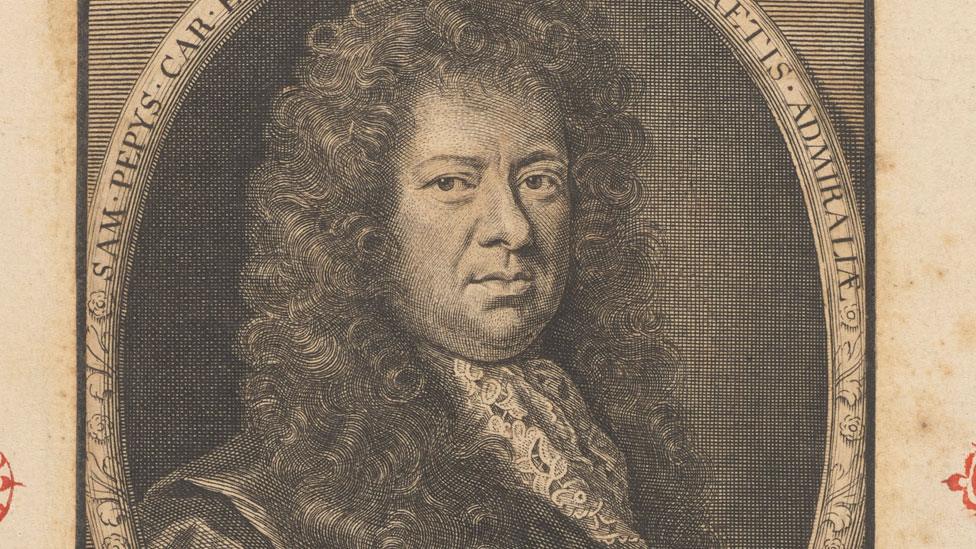

A series of French fashion engravings reveal how Samuel Pepys remained fascinated by the power of fashion throughout his long life, according to a researcher.

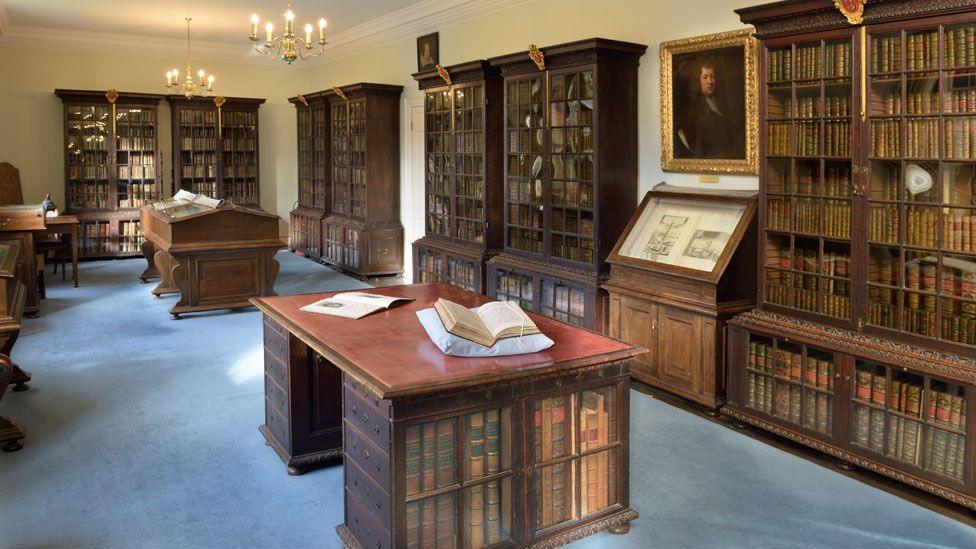

Best known for his diaries, the tailor's son was also a bibliophile who bequeathed his large library to the University of Cambridge's Magdalene College.

It included one of the largest bound collections of late 17th Century fashion prints in the world, eight of which are being published online for the first time, external.

Marlo Avidon's research suggests Pepys never shook off his "sense of anxiety" about dressing inappropriately for his station in life, despite his subsequent success.

Pepys was both fascinated by - and disapproving of - French fashion, collecting more than 100 illustrations between 1670 and 1696, said Marlo Avidon

"The need to be fashionable was very directed towards women, but in lots of ways men were just as susceptible, if not more," said Miss Avidon.

She studied the collection as part of her PhD research into the role of fashion in identity construction of elite late 17th Century women.

"What is unique about Pepys is we have documentary evidence in his diary of an interest in fashion and also a sense of anxiety at a time when people could climb quite quickly into civil service and into court life," she said.

"You need to dress the part to assert your place in society."

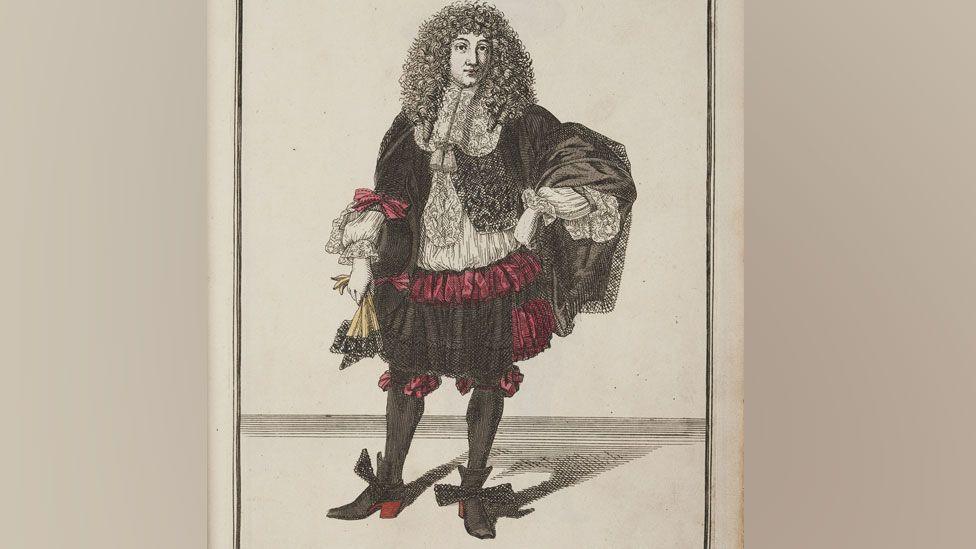

Some of the prints Habit Noir (above) "were clearly not professionally coloured, they look amateurish", said Miss Avidon

Samuel Pepys' diary (1660 to 1669) shone a spotlight on Restoration London, covering the ups and downs of his marriage, as well as events such as Charles II's coronation and the Great Fire of London.

It included an episode in which Pepys was "afeared to be seen" in a summer suit he had just bought "because it was too fine with the gold lace at the hands".

He finally plucked up the courage to do so, only to be told by a socially superior colleague that the sleeves were above his station. He decided "never to appear in Court" with the sleeves and made a tailor cut them off.

Towards the end of his diary, the naval clerk (civil servant) was on the cusp of professional success. In the next decades he helped establish the Royal Navy, became an MP, was locked up in the Tower of London, elected the President of the Royal Society and died a prosperous man in 1703.

This image of a fashionable city gown also has amateurish squiggly lines and Miss Avidon suggests Pepys' long-term mistress Mary Skinner may be responsible

The collection of fashion prints suggested the episode with the sleeves did not put him off fashion - and French fashion at that.

The diary revealed his anxiety about a growing French influence on English culture, despite his marriage to Elizabeth, who was French, and his friendships with French merchants.

His wife died soon after the couple went on a trip to Paris in 1669 and Miss Avidon believed "these prints of fashionable young women must have reminded Pepys of Elizabeth".

His teenage housekeeper Mary Skinner swiftly became his mistress and they stayed together for the rest of his life.

'Cultured and fashionable'

Pepys' active role in his wife's education, including lessons in drawing and "fostering her in gentlewomanly interests", can be clearly seen in the diary, said Miss Avidon.

She suggests he probably did the same with Mary Skinner, about whom little is known.

"I would speculate, but you can see some of the fashion prints were coloured in a fairly rough hand and it wouldn't be a huge leap to surmise these prints could have been a means of instructing Mary on drawing and on fashion," she said.

"When she died in the early 18th Century, she was cultured and fashionable, leaving all her gowns to her nieces and ornate Japanese imported screens and furniture."

In contrast, this 1695 drawing of an elite French woman in the 17th Century's version of informal loungewear, looks more professionally coloured

The PhD student admitted what she knew about Pepys' diary had "clouded my opinion of him and Restoration society".

Miss Avidon said: "So much of it is quite crude and what stood out to me was that he was immensely jealous of his wife and controlling and relatively cruel to other women in his life, whether close to him or random women on the street.

"He is also hypocritical of Restoration court debauchery while behaving more or less the same."

Her research enabled her to look through his later correspondence and now she sees "a very human person... haunted by anxiety".

"He is someone who can be crude and cruel and also incredibly funny and insightful, and very on the nose about the world he lives in," she said.

Miss Avidon's research is published in the journal, The Seventeenth Century.

Pepys' collection of 3,000 books is housed in the bookcases he had made for them at the Wren Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge

Follow Cambridgeshire news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp us on 0800 169 1830

Related topics

- Published19 April 2024

- Published7 August 2023

- Published4 April 2019