What is mpox and how is it spread?

- Published

The World Health Organization (WHO) has said recent mpox outbreaks in parts of Africa are a public health emergency of international concern.

Cases of this type of mpox have since been detected in the UK as well as in Sweden and Germany.

Experts say it is unlikely to spread more widely in Europe, but that the situation is more dangerous in central and east Africa where vaccines are in short supply.

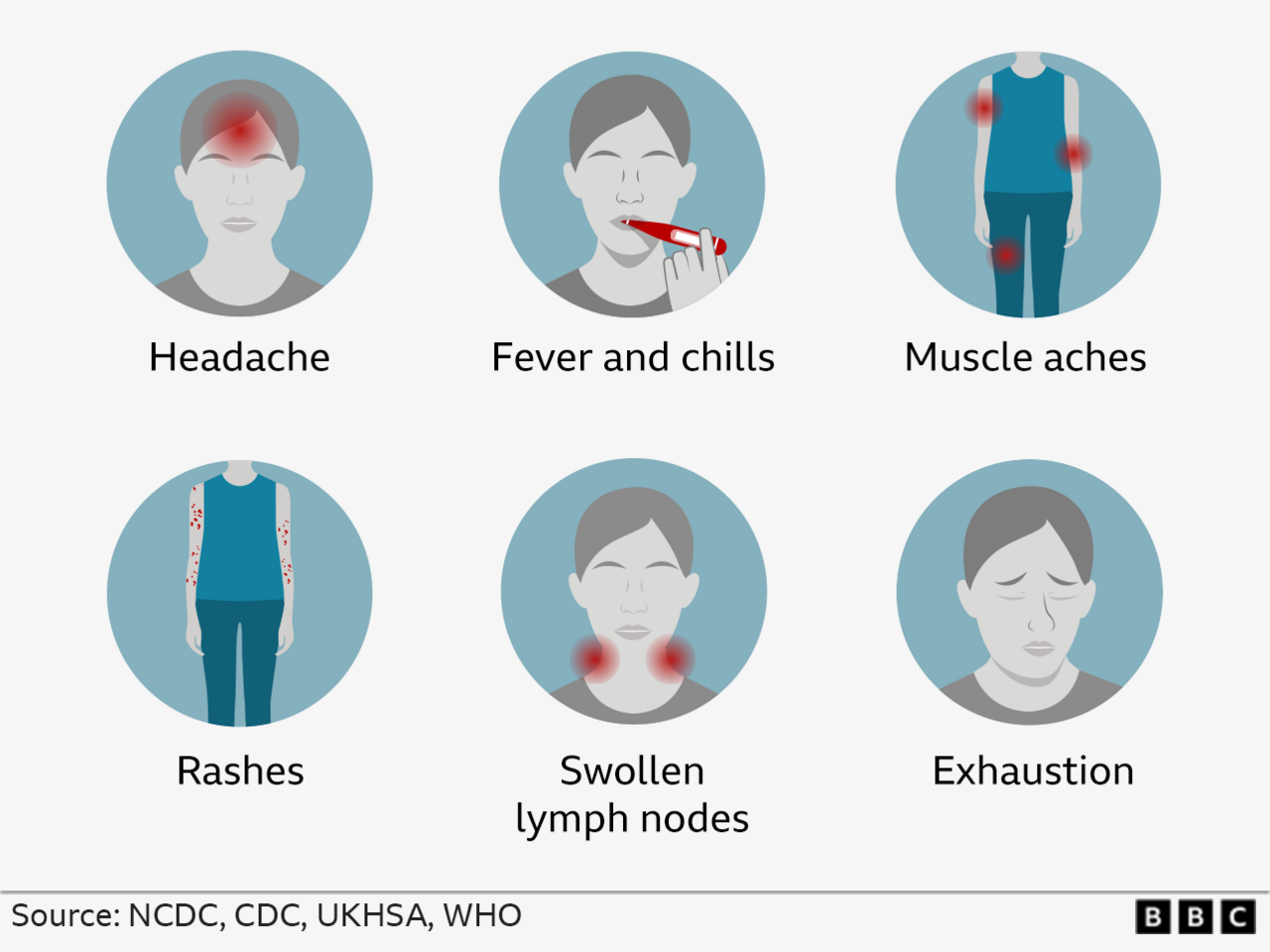

What is mpox and what are the symptoms?

Mpox is caused by a virus in the same family as smallpox but is usually much less harmful.

It was originally transmitted from animals to humans but now also passes between humans.

Initial symptoms include fever, headaches, swellings, back pain and aching muscles.

Once the fever breaks, a rash can develop. This can be extremely itchy or painful, often beginning on the face before spreading to other parts of the body, most commonly the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.

In serious cases, lesions can attack the whole of the body, especially the mouth, eyes and genitals.

The rash goes through different stages before finally forming a scab, which later falls off. It can cause scarring.

In many cases the infection lasts between 14 and 21 days before clearing up on its own.

But mpox can be fatal, particularly for vulnerable groups - including small children.

Where has mpox been found, and how many people are affected?

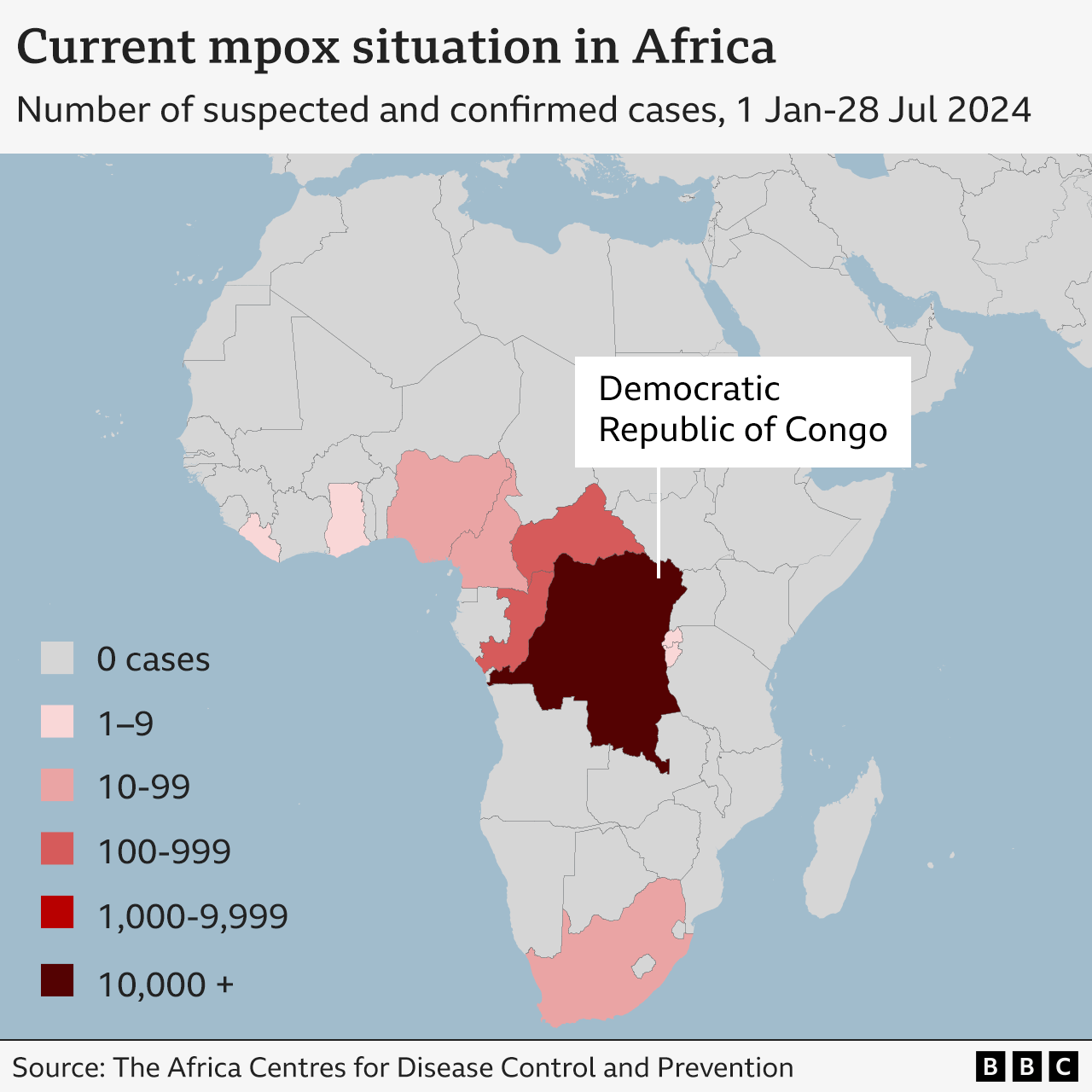

More than 10,000 cases of mpox were recorded in the DR Congo between January and July 2024

Mpox is most common in remote villages in the tropical rainforests of West and Central Africa, in countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where it has been seen for many years.

In these regions, there are thousands of infections and hundreds of deaths from the disease every year, with children under 15 worst affected.

There are currently a number of different outbreaks happening simultaneously - mainly in the DRC and neighbouring countries.

The disease has also been seen in Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda and South Africa.

There are broadly two main types of mpox - Clade 1, which is often more serious, and Clade 2.

A previous mpox public health emergency, declared in 2022, was caused by the relatively mild Clade 2.

It spread to nearly 100 countries which do not normally see the virus, including some in Europe and Asia, but was brought under control by vaccinating vulnerable groups.

Experts are now concerned about Clade 1 virus that has been spreading quickly in west and central Africa since 2023.

More children than adults have been linked to a relatively new and more severe strain of mpox known as Clade 1b.

Experts are still learning about Clade 1b but warn it appears to spread more easily and cause more serious disease.

The Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) agency says there were more than 14,500 mpox infections and over 450 deaths between January and July 2024.

That represents a 160% increase in infections and a 19% increase in deaths compared with the same period in 2023.

Cases have been confirmed in other continents - including Europe - linked to travel.

Four cases of Clade 1b have been recorded in the UK, external.

The first UK patient had recently been on holiday in at least one of the affected countries in Africa, and began to feel sick 24 hours after coming home. Three other people in their household then fell ill with it.

Mpox risk low but UK medics on alert

- Published15 August 2024

First case of more dangerous mpox found outside Africa

- Published15 August 2024

How is mpox spread?

Mpox spreads from person to person through close contact with someone who is infected - including through sex, skin-to-skin contact and talking or breathing close to the ill person.

The virus can enter the body through broken skin, the respiratory tract or via the eyes, nose or mouth.

It can also be spread by touching objects which have been contaminated by the virus, such as bedding, clothing and towels.

Close contact with infected animals, such as monkeys, rats and squirrels, is another route.

During the 2022 global outbreak, the virus spread mostly through sexual contact.

The recent outbreaks in DR Congo were also largely driven by sexual transmission, although mpox has been found in other vulnerable communities as well - including young children.

Who is most at risk from mpox?

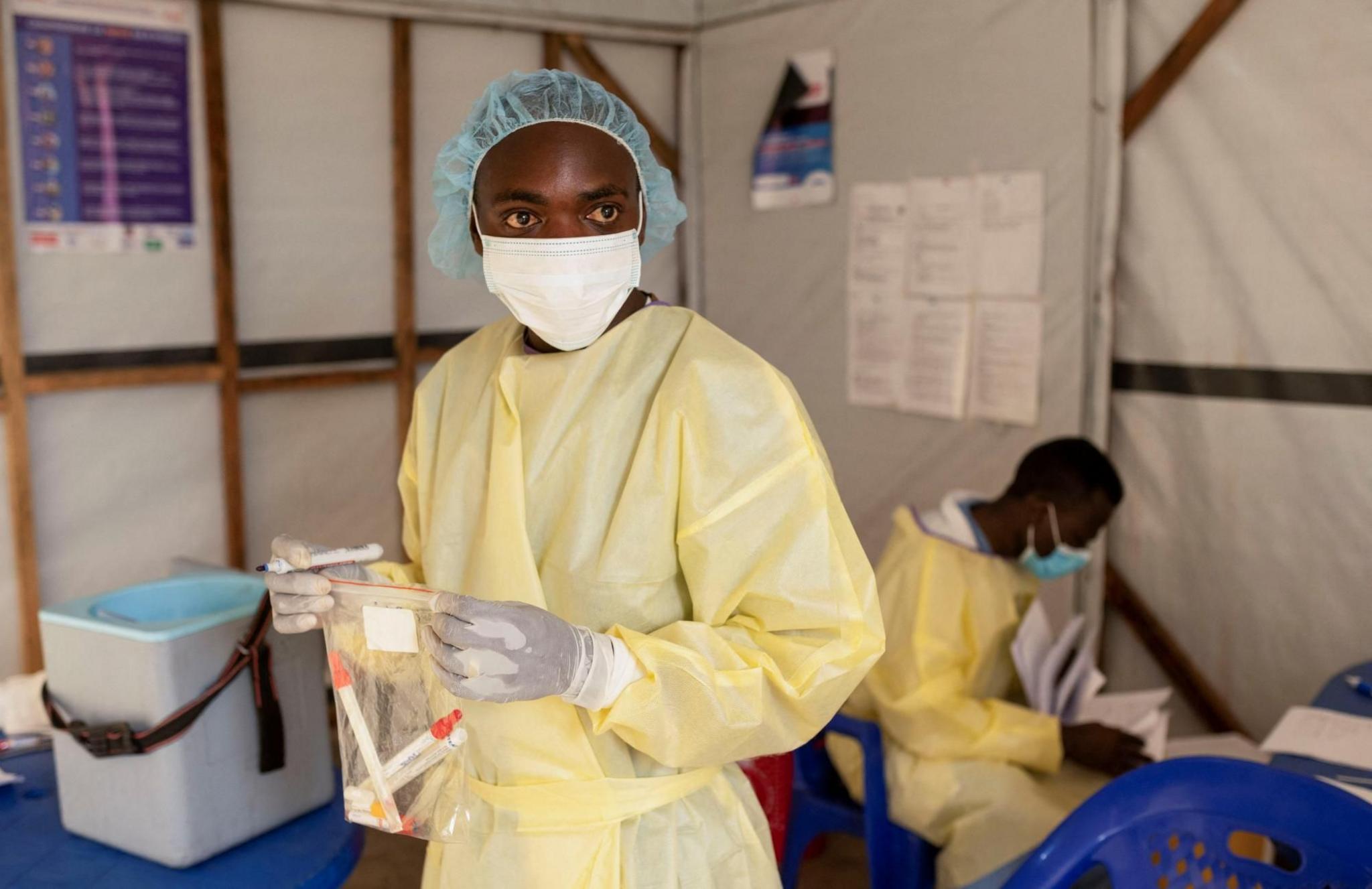

There are vaccines which protect against severe mpox

Anyone who has sex or other close physical contact with someone with symptoms can catch the virus, including health workers and family members.

Young children may be particularly vulnerable because their immune systems are still developing, and - in some countries where mpox has spread - have poor nutrition, which makes it harder to fight off disease.

Unlike some older people, children have also not had access to the smallpox vaccine, which was discontinued more than 40 years ago.

Anyone with a weakened immune system may also be more prone to the disease, and pregnant women may also be at greater risk.

The advice is to avoid close contact with anyone with mpox, and to clean your hands with soap and water regularly if the virus is in your community.

Those who have mpox should isolate from others until all their lesions have disappeared.

Condoms should be used as a precaution when having sex for 12 weeks after recovery, the WHO says.

Is there an mpox vaccine?

Vaccines do exist but are generally only available to those people at higher risk or who have been in close contact with an infected person.

The WHO has asked drug manufacturers to makes their vaccines available for emergency use, even if they are still waiting for formal approval.

Japan and the US are sending vaccines to DR Congo, where authorities hope to vaccinate 2.5 million people.

The Africa CDC has pledged to provide 10 million vaccines by 2025.

The WHO hoped that its decision to declare a continent-wide public health emergency would increase the flow of medical supplies and aid into affected areas, and make it easier for governments to co-ordinate their response.

Without global action, there is real concern the current outbreak could spread significantly.