Eurovision: What does the UK have to do to win?

Olly Alexander came 18th out of a possible 25 at this year's Eurovision

- Published

The plan was called Project Cauliflower.

It began last October, when Olly Alexander accepted the invitation to become the UK’s Eurovision contestant.

He’d been in the running once before, in 2022, but the timing didn’t seem right.

Instead, the BBC sent a little-known TikTok singer called Sam Ryder, with a power ballad called Spaceman.

It went on to achieve second place - the UK’s best result in more than 20 years.

The following summer, Alexander started recording his first album as a solo artist. Maybe one of these songs, he thought, would work at Eurovision?

Calls were made. Deals were made. Project Cauliflower was born and, for the next two months, preparations began under the strictest secrecy.

“We had to have meetings at Olly’s manager’s house so no-one could overhear what was happening,” creative director Theo Adams told The Euro Trip podcast, external.

“It was actually a very exciting period. I’d never done anything before that had such secrecy surrounding it. I felt like I was a spy.”

Alexander went public in December during the grand finale of Strictly Come Dancing. For Eurovision fans, it seemed too good to be true.

A likeable, chart-topping pop star, known around the world, with a track record of putting on elaborate performances and a lifelong love for Eurovision?

He couldn’t have been a better fit.

Swiss singer Nemo lifted the famous crystal trophy, with their song The Code

"Having a bona fide pop star representing the UK this year is a great start,” agreed Graham Norton in an interview earlier this week.

“Olly has already done all the things that it’s impossible to prepare someone for - he has played to huge crowds, he can relate to the cameras, and he is used to high pressure situations.”

“He’s a great performer, and a great singer,” agreed Neil Tennant, who duetted with Alexander on the 2020 Pet Shop Boys’ song Dreamland.

“I think it’s great he’s got the courage to do it because it’s so high stakes, isn’t it?”

The stakes got him in the end.

In Malmö on Saturday, Alexander’s song, Dizzy, stumbled into 18th place, out of 25.

All of his 46 points came from the jury. His score in the public televote was zero.

Even so, it wasn’t the worst result. The UK has had more embarrassing defeats. And Alexander has a career to go back to - unlike previous performers, whose musical ambitions have come to a screeching halt after Eurovision.

But the expectations were so high that this year's result feels particularly rough.

It's now 27 years since the UK last won the contest.

So what went wrong… and how can the country improve its chances?

1) Was it the song?

Olly Alexander wrote Dizzy last summer as he was creating his latest album

Look, Dizzy is a great radio track.

Co-written by Danny L Harle (Charli XCX, Dua Lipa) it pulses and throbs in all the right places. Musical nods to the Pet Shop Boys and London's church bells remind listeners of the UK's place at the epicenter of pop.

And compositionally, it pulls a clever trick. The constant chordal movement of the chorus prompts a feeling of dizziness. When Alexander sings that his lover “pulls me back to the beginning”, the chords resolve to the opening key of C minor.

That’s why juries liked it. Songwriters in Sweden, another pop powerhouse, awarded Dizzy eight points out of a possible 12.

But audiences don’t know or care about the nuts and bolts of songwriting. They sided with critics like the Guardian’s Laura Snapes, who dismissed the song as “perfectly fine, external” or the Telegraph’s Neil McCormick, who called it “pleasantly unexceptional, external”.

Dizzy wasn’t a bad song. It just wasn’t good enough to make people pick up the phone and vote.

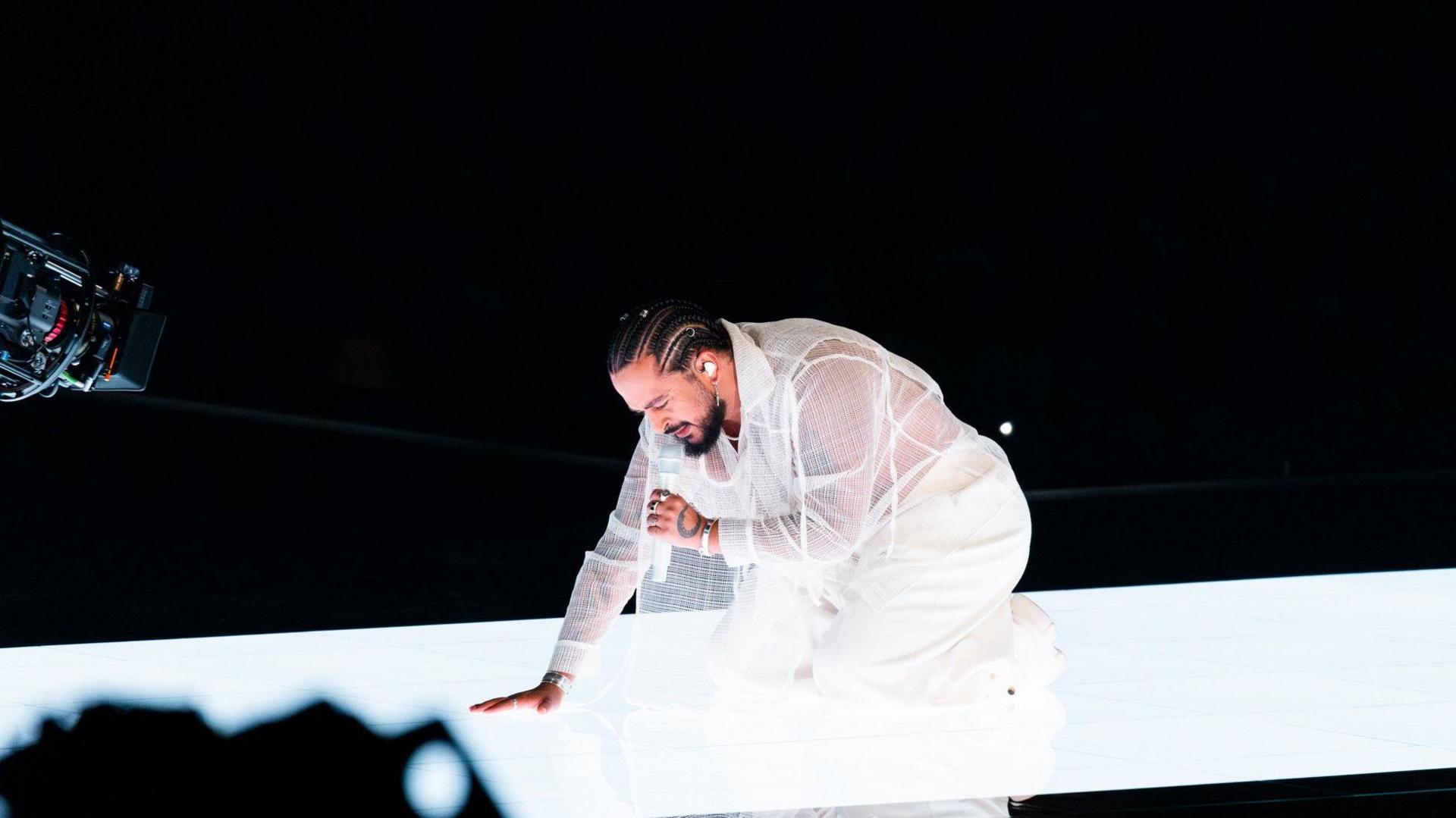

2) Was it the performance?

Olly Alexander gets nothing from the audience

I'd like to think not.

After years of sending untested, milquetoast reality show contestants to Eurovision, Alexander delivered a spectacular TV performance.

With computer-controlled cameras, synchronised to pin-sharp choreography, the star made it seem like he and his dancers were being flung around the interior of a spaceship plummeting through a black hole.

From his commentary box, Graham Norton described the production as “terrific” but admitted it could suffer because it was “so different to everything else in the contest tonight”.

The performance drew a lukewarm reception inside the arena, as the complex staging meant Alexander was out of sight for the first two minutes.

And at home, some viewers said they were put off by the sexual nature of the dancing.

Others said the physical demands affected Alexander’s vocals. There were certainly a few wobbles - a bad look next to the powerhouse singers of France and Portugal and Switzerland.

But there were positive comments, too. “Olly Alexander did an amazing job,” tweeted journalist Emilia Kettle, external from inside the arena.

"Best performance of the night so far,” added Craig Brown, external. “Maybe not the best song. But the best live act."

That’s a big step up. Eurovision performances have become increasingly elaborate and the UK needed to catch up. From here, things can only get better.

Switzerland's Nemo wins Eurovision as UK comes 18th

- Published12 May 2024

Olly Alexander: 'I looked up my Eurovision odds'

- Published10 May 2024

Top moments from Eurovision Song Contest 2024 in pictures

- Published12 May 2024

Eurovision queen Loreen: 'I want to write a boring song'

- Published11 May 2024

3) Was it a lack of emotional connection?

French star Slimane was forlorn and heartbroken during his performance of Mon Amour

I don’t know what inspired Dizzy. It seems like an earnest and heartfelt declaration of love, but is that enough?

Listen to the acts who came in the top five, and you'll hear something - an urgency? - that Alexander lacked.

Nemo’s winning song, The Code, external, was a viscerally moving account of accepting their non-binary identity, after years of thinking there was something wrong with them.

Israel’s song Hurricane, external was contentious for many reasons, but the desperate conviction of Eden Golan's ode to missing friends in the midst of a war was palpably raw.

And the scorching intensity of French star Slimane helped his song, Mon Amour, external, into fourth place.

Even Croatia’s Rim Tim Tagi Dim, external packed a punch.

A superficially silly techno stomper, it was written about the loss that singer Marko Purišić felt after his best friend left their hometown for a better life. It has subsequently become a big hit among the Croatian diaspora in Europe.

Dizzy simply never achieved that level of emotional connection.

4) Is the UK playing it too safe?

By tearing up the rule book, Ireland scored its best Eurovision result in 25 years

This one's hard to quantify - but have you noticed how many Eurovision songs have succeeded by taking wild creative swings?

Finnish star Käärijä stormed the public vote last year with Cha Cha Cha, external, an intoxicating blend of industrial metal and hyperpop that sounded like nothing else on planet earth.

Ireland’s Bambie Thug pulled a similar trick this year, with the weird and witchy Doomsday Blue, external – a song so shocking that one Irish priest declared the country was “finished” after sending it to Malmö.

But Johnny Logan – a man who knows a thing or two about Eurovision, having written three winning entries - disagreed.

“The one thing about the Eurovision Song Contest is that every year people try to copy the song that won before, because they think that’s the secret to winning it," he told Ireland's Sunday World newspaper.

"This year’s Irish entry doesn’t do that."

The UK has tried to second guess Eurovision for years, but the safe choice isn’t always the wisest one.

Could we cast the net wider and look at new genres, or musicians from different backgrounds, instead of aiming for a radio-friendly pop hit?

5) Or is it just luck?

Rosa Linn triumphed after coming 20th in the 2022 edition of Eurovision

A hit song requires magic, not a formula. And Eurovision is no different.

You’ve got to balance the desires of the TV audience and the professional juries, while finding a performer who can play to an arena, while hitting their marks for a TV show. Your place in the running order counts, too.

And sometimes, a great song just gets overlooked.

Back in 2022, Armenian singer Rosa Linn came 20th with her song Snap, external. She went home feeling she'd disappointed her country. Then, months later, the track went viral on TikTok. It's now the second-most streamed Eurovision song of all time, with more than 1 billion plays on Spotify alone.

Olly Alexander might not see those numbers for Dizzy, but nor did he embarrass himself in Sweden.

The staging and the song and the concept all worked, and they laid solid foundations for next year.

Maybe all we need to change is the code name.

Project Turnip, anyone?