New study challenges united Ireland cost

The initial cost of a united Ireland could be about €2.5bn, Prof Doyle says

- Published

Public sector salaries in Northern Ireland would only gradually catch up with those in the Republic after Irish unification, a new study suggests.

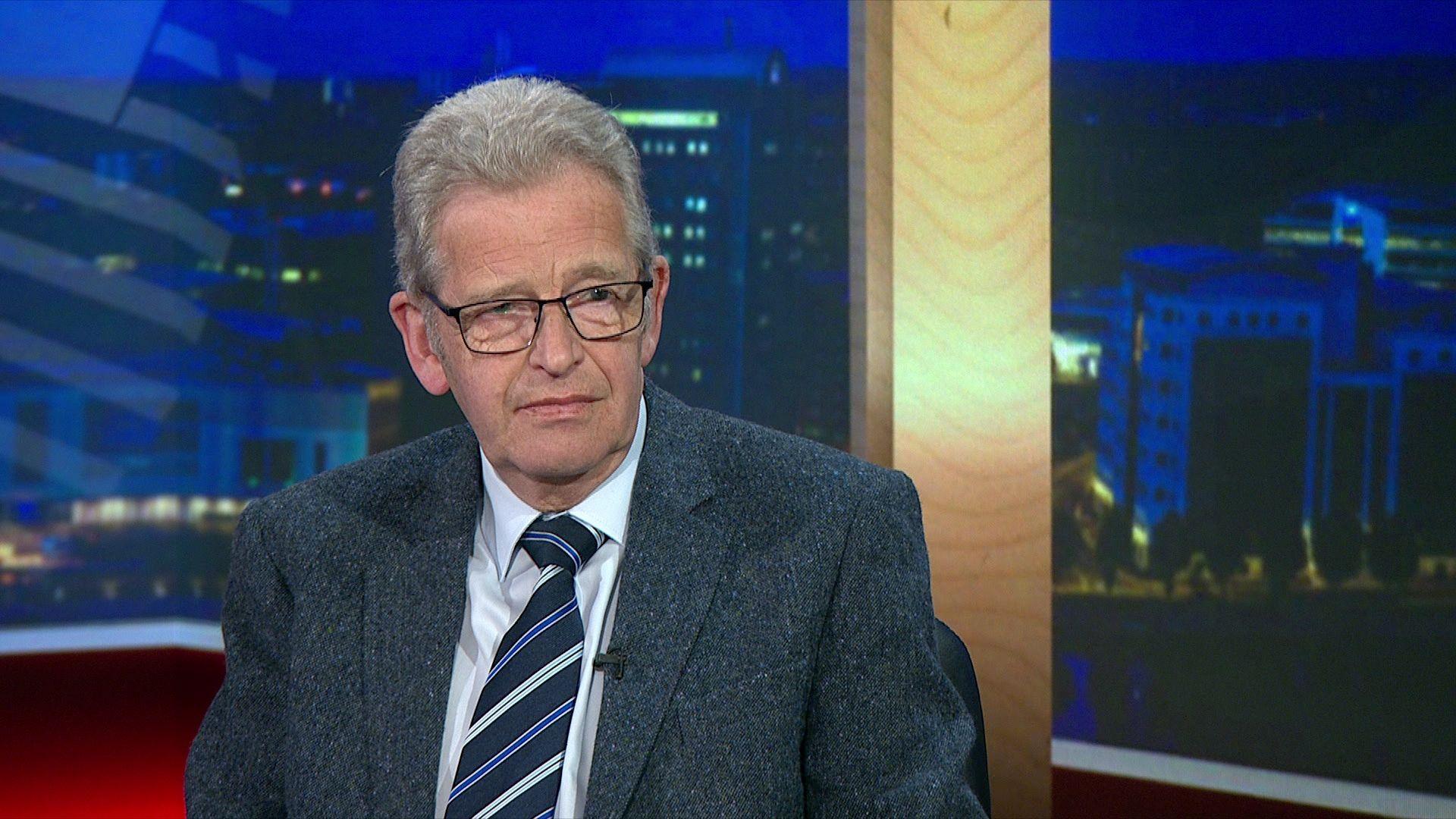

Prof John Doyle of Dublin City University challenged some assumptions in a report on the economics of unification published in April.

That work, published by the Institute of International and European Affairs (IIEA), suggested the initial cost of a united Ireland could be up to €20bn (£17.15bn) a year.

Prof Doyle said some of the assumptions underpinning that total are "entirely unreasonable" and his estimate is an initial €2.5bn cost.

The cost of living in Northern Ireland would not change immediately, Prof Doyle thinks

The IIEA study, written by economists John Fitzgerald and Edgar Morgenroth, focused on the subvention - the shortfall between what is raised in taxes in Northern Ireland and the amount spent on public services.

They estimated that the subvention in 2019 was just under €11bn (£9.4bn) meaning the Irish state would need to find that money to provide public services to the state's new population in what had been Northern Ireland.

They suggested that if social security benefits and public sector wages in Northern Ireland were immediately raised to match levels in Ireland the subvention would jump to more than €20bn (£17bn), equivalent to 10% of national income.

Prof Doyle said it was unrealistic to assume salaries would immediately be equalised and even if they were the IIEA paper had taken no account of the additional taxes which would be collected from public sector workers.

He said: "The IIEA report assumed that public service salaries in Northern Ireland would be immediately increased to Southern levels in year one. This is unrealistic and unnecessary, as the cost of living in Northern Ireland would not change immediately.

"Convergence will happen over time and will involve negotiations with public sector trade unions. Merging salary levels over 15 years – half the time taken by Germany, would mean a cost of approximately €133m (£96.3m) in year one, rising on average by that amount each year."

NI salaries would not immediately equalise with ROI salaries, Prof Doyle says

UK state pension?

Current structural differences between the Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland economies include higher average salaries in the Republic but also higher housing costs.

The major difference between Prof Doyle’s overall approach and that of the IIEA is around the sort of deal which would be struck between the UK and Ireland at the point of unification.

Prof Doyle assumes a good deal for Ireland where the UK writes off Northern Ireland’s share of UK debt and continues to pay state pensions to people who are already receiving them.

He acknowledged that the UK state pension is effectively a benefit which is paid out of current taxation but argues that it has different characteristics from other benefits.

"Like Ireland, all social welfare-based ‘state’ pensions and most public sector employment-based pensions are paid from general taxation and not from a legally separated fund," he wrote.

"However, there is a strong sense of pension ‘entitlement’ in both Ireland and the UK, notwithstanding the absence of legally separate pension funds."

The IIEA paper takes no account of the additional taxes which would be collected from public sector workers, says Prof Doyle

'Never any question of UK having a liability'

The IIEA study assumes a less benign deal for Ireland saying it is "unlikely" that the UK would continue to pay pensions to people in Northern Ireland.

It uses the example of Irish independence in 1922 saying "there was never any question of the UK having a liability after independence to the then social insurance scheme, which covered unemployment rather than pensions. It was funded on a pay-as-you-go basis."

The IIEA paper is also relatively pessimistic about Northern Ireland’s prospects for catching up with the level of economic productivity in the Republic of Ireland suggesting it would take 20 years "even under the most favourable circumstances with optimal policies".

Prof Doyle sketches a more optimistic scenario drawing on the experience of "catch up" growth among poorer economies after they joined the EU.

"Ireland’s own experience of growth following EU membership to catch up on wealthier economies was not unique," he said.

"It was also seen in Spain and Portugal, Greece and most recently in Central Europe. Convergence with European economic performance does not require a ‘miracle’ growth path, but it does require change."

On Tuesday Profs Fitzgerald and Morgenroth will be talking about their paper at the IIEA and taking questions from journalists.

Related topics

- Published10 May 2024

- Published6 April 2024

- Published4 April 2024