Huge Saudi construction projects 'might get scaled down'

The Line, a planned 170km long linear city, may now initially extend for only 2.4km

- Published

“They can keep saying that, and we can keep proving them wrong.”

That was the response of Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in a TV documentary broadcast in July 2023, while talking about scepticism surrounding Saudi Arabia’s flagship construction projects.

Almost a year later, some of the doubts are turning out to be true.

In recent months, Saudi Arabia has seemingly scaled back plans for its vast desert development project Neom, which is the centrepiece of Vision 2030.

This is the economic diversification programme spearheaded by Prince Mohammed, the Gulf state’s de-facto ruler, to transition the country’s economy away from oil-dependency.

As well as Neom, Saudi Arabia is also developing 13 other large construction schemes, or “giga projects” as they are referred, worth trillions of dollars. These include an entertainment city on the outskirts of the capital Riyadh, multiple luxury island resorts on the Red Sea, and a cluster of other tourist and cultural destinations.

But low oil prices have impacted government revenues, forcing Riyadh to reassess these projects, and explore new funding strategies.

An advisor, who is associated with the government but wished not to be named, tells the BBC that the projects are being reviewed, with a decision expected soon.

“The decision will be based on multiple factors,” he says. “But there is no doubt that there will be a recalibration. Some projects will proceed as planned, but some might get delayed or scaled down.”

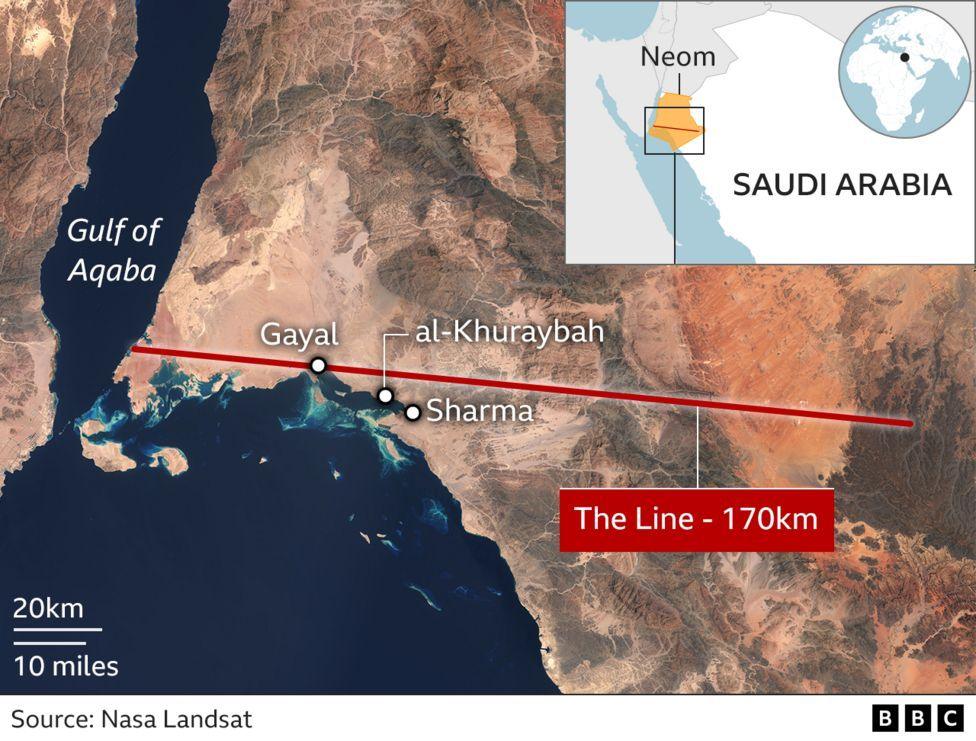

Announced in 2017, Neom is a $500bn (£394bn) plan to build 10 futuristic cities in a desert region in the north west of the country.

The most ambitious of them, and the one that has gained all the headlines, is The Line. This will be a linear city consisting of two adjoined, parallel skyscraper walls standing 500m high - taller than the Empire State Building. Yet they will have combined width of just 200m, including the gap between them.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is seeking to diversify the country's economy

The original plan was that they would extend for 170km (105 miles), and become home to nine million inhabitants.

But according to people familiar with the details – and as already leaked to the press - the project developers will now focus on completing just 2.4km by 2030, as part of the first module.

When The Line was first announced it was billed as a “carbon-free linear city” that would redefine urban living, with amenities for residents like parks, waterfalls, flying taxis, and robot maids.

The city would have no roads or cars, and would be made up of interconnected, pedestrianised communities. It would also include an ultra-high-speed train, with a maximum journey duration of 20 minutes anywhere within city limits.

How many of these features will be part of the first phase are unclear.

Along with The Line, Neom is also due to include an octagon-shaped floating industrial city, and a mountain ski-resort that will host the Asian Winter Games in 2029.

Ali Shihabi, a former banker now on Neom's advisory board, says the targets set for projects under Vision 2030 were deliberately “designed to be over ambitious”.

“It was meant to be over ambitious, with the clear understanding that only a part of it would be delivered on time. But even that part would be significant,” says Mr Shihabi.

The scaling back of Neom has put the spotlight on the funding challenges that the Saudi government is facing.

Neom is being paid for by the Saudi government through its sovereign wealth entity, the Public Investment Fund (PIF).

The official cost to build Neom, $500bn, is 50% more than the country’s entire federal budget for the year. But analysts estimate that it would ultimately cost more than $2tn to execute the full project.

Saudi Arabia’s government budget has been in a deficit since late 2022, when the world’s largest oil exporter began slashing production to accelerate global prices. The government has forecast a deficit of $21bn for this year.

The PIF is feeling the pinch. It controls assets of about $900bn, but it had just $15bn in cash reserves as of September.

Tim Callen, the former IMF chief to Saudi Arabia and now a visiting fellow at the Arab Gulf States Institute, says that raising capital for Neom and other large-scale projects is a key challenge in the future.

“It is going to be increasingly challenging to fund the PIF to the levels that are required for these projects,” Mr Callen says.

The Gulf state is tapping other avenues to shore up capital.

Earlier this month, it sold roughly $11.2bn worth of shares in its national oil company Saudi Aramco. Most of those proceeds are expected to go to the PIF, which was also the biggest beneficiary when the company went public in 2019.

The sale comes amid volatility in oil prices. In July of last year, in an attempt to bolster prices, the Saudi Arabia-led OPEC+ oil producing group of countries curbed production.

Riyadh voluntarily cut its supplies by one million barrels a day. However, this month, OPEC+ reversed the decision, and it will gradually start increasing production from October.

According to the International Monetary Fund, the price of a barrel of oil needs to be $96.20 for Saudi Arabia to be able to balance its budget. Brent, one of the main benchmarks for crude, has been hovering around $80 a barrel.

The country has also relied on selling government bonds to maintain funding flows for the PIF. The other challenge has been that foreign direct investment has remained far below targets, underlining Riyadh’s struggle to attract funding from private companies and international investors.

‘It’s going to be very difficult to persuade investors to come into projects that they view as being overly ambitious,” says Mr Callen. “It’s unclear where your returns will ultimately come from.”

The Gulf state is also funnelling money into sectors such as tourism, mining, entertainment, and sports as part of the economic diversification strategy.

In recent years, Saudi Arabia has won the hosting rights for several major international events, such as the football Asian Cup in 2027, Asian Winter Games in 2029, and the World Expo 2030. It has also emerged as the sole bidder for the 2034 FIFA Men’s World Cup. All these projects will require massive investments in the years to come.

Mr Shihabi expects the government to prioritise these international events as they get closer. “Projects where we have specific deadlines to meet will get prioritized by the nature of things,” he says.

In April, at a special meeting of the World Economic Forum meeting held in Riyadh, the country’s Finance Minister Mohammed Al-Jadaan said the government didn’t have an “ego”, and would adjust its Vision 2030 plan to transform its economy as needed.

“We will change course, we will extend some of the projects, we will downscale some projects, we will accelerate some projects,” he said.

Read more

Saudi forces 'permitted to kill' for new eco-city

- Published9 May 2024

Is Saudi Arabia's 100-mile eco-city too good to be true?

- Published22 February 2022