University makes robotic hand 'breakthrough'

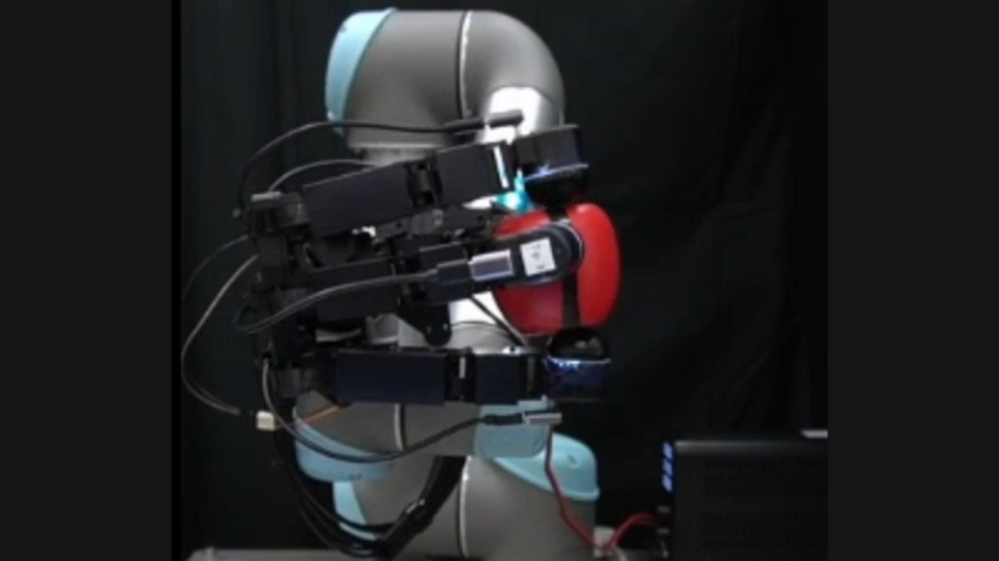

Developed by the University of Bristol, the tactile robotic hand can rotate objects

- Published

University researchers say they have made a "key breakthrough" in the development of tactile robotic hands.

Led by Prof Nathan Lepora, a professor of robotics and AI, at the University of Bristol has created a four-fingered robotic hand which is capable of rotating balls and toys in any direction and orientation.

The improvement in dexterity could have significant implications for automating tasks such as handling goods for supermarkets or sorting through waste for recycling.

The next steps for this technology is to move to more advanced examples of dexterity, such as manually assembling items like Lego.

OpenAI became the first to show human-like feats of dexterity with a robot hand in 2019, but it soon disbanded its robotics team.

Its set up had included a cage holding 19 cameras and more than 6,000 central processing units (CPUs) to learn huge neural networks which could control the hands.

Prof Lepora wanted to see if similar results could be achieved with more cost-efficient methods.

Four teams from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of California in Berkeley, Columbia University in New York, and Bristol achieved robotic hand dexterity feats using "simple set-ups" and desktop computers.

A sense of touch was built into the robotic hands by the teams

Developing a high-resolution tactile sensor became possible thanks to advances in smartphone cameras which are now so tiny they can comfortably fit inside a robot fingertip.

Prof Lepora said his team created an artificial tactile fingertip that used a 3D-printed mesh of pin-like papillae (similar to the bumps on a tongue) on the underside of the skin, based on copying the internal structure of human skin.

“These papillae are made on advanced 3D-printers that can mix soft and hard materials to create complicated structures like those found in biology," he said.

Prof Lepora added that the robot would initially drop the object, but his team found the right way to train the hand using tactile data.

"It suddenly worked even when the hand was being waved around on a robotic arm," he said.

Prof Lepora’s research was possible after receiving a Leverhulme Trust Research Leadership Award.

Follow BBC Bristol on Facebook, external, X, external, and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to us on email or via WhatsApp on 0800 313 4630.

Related topics

- Published30 May 2024

- Published15 June 2024

- Published24 May 2024