Bristol's hidden history of forgery and tragic deaths

Unknown to some, dotted around the city are surviving relics of the past

- Published

As you wander through the streets of Bristol, it is easy to see how it has proved the backdrop for literary icons, political figures, and many pivotal moments in history.

But how much of these stories still remain and are known to the city's dwellers?

The school façade faces St Mary Redcliffe Church across the road

If you have ever driven down Bristol's Redcliffe Way and marvelled at the peculiar façade of an 18th century building - it harbours a fascinating story of poverty, forgery, tragic death and medieval poetry.

Nicknamed 'Bristol’s Shakespeare', literary genius Thomas Chatterton was born in the schoolmaster's house of Pile Street School in 1752, where his late father was a writing master.

Among his father's belongings were forgotten medieval documents he had rescued from a chest in the muniment room of St Mary Redcliffe Church, which cast a large gothic shadow over their modest home from across the street.

It is thought that these ancient deeds inspired Chatterton to create his own medieval works, which he then attributed to a fictional 15th century monk named Thomas Rowley.

Chatterton was admitted as a pupil to Pile Street School at the age of five

After these spurious documents were rejected by publishers, Chatterton left for London in April 1770 to pursue his writing career, but died just four months later from arsenic poisoning.

His tragic demise at the age of 17 cemented his legacy as a romantic figure.

"Chatterton had ample funds to buy food and cover his other expenses, so it wasn't want that took him to the grave," said Richie Fenlon, from the Thomas Chatterton Manuscript Society.

"He was self-medicating for an STD with laudanum, or a lethal mixture of Calomel and Vitriol, and suffered an unintentional overdose which resulted in his death."

Italian restaurant La Panza now occupies his old home on Redcliffe Way, nestled behind the façade of where his former school once stood.

The cobbles which once lined the street can still be seen between the tracks

If you're popping for an appointment at Gloucester Road Medical Centre in Horfield, odds are you've walked right alongside a set of old tram lines, which were rendered out of action by a German bomb.

Bristol was once highly regarded as a pioneering city in urban transport, with the first horse-drawn tram appearing in the city in 1875.

Two decades later, electric trams were introduced. At its peak, there were 17 routes and 237 tramcars in use across the city, with a system stretching its tendrils from Broadmead to Filton.

The Grade II* listed electricity generating station is still standing beside St Philip's Bridge

This was until 11 April 1941, when the Luftwaffe's Good Friday air raid snatched the system away in one foul blow.

The Bristol Blitz set the central city on fire, and a bomb dropped on St Philip's Bridge severed Bristol Tramways' entire electricity supply, which came from the generating station beside the river.

Today, all that remains of the ground-breaking network are the parallel scars it left behind in the concrete.

Charlie Revelle-Smith, author of Weird Bristol, says the city has played a "significant role in almost every major event in British history."

"Once you start peeling back the layers, you soon discover that evidence of this history is all around us.

"Suddenly, this hidden story of our past doesn’t seem so hidden anymore."

The statues, made by Julian Warren in 2016, depict the animals in weird and wonderful positions.

In a city renowned for its immersive street art, spotting a sculpture or two on your way to work is not unusual.

But among those you may not know of is a collection of bronze monkeys dotted around Clifton that provide a glimpse into a past day of pure chaos.

In 1934, 12 Rhesus monkeys escaped from the Monkey Temple enclosure at Bristol Zoo and wreaked havoc all over the city, with one even sneaking into a Clifton College dormitory.

The Rhesus monkeys moved out of the enclosure in the 1980s, to enjoy a more natural habitat with trees, islands and lakes

Most were retrieved fairly quickly, but the final monkey was on the run for almost a week before zookeepers managed to lure him back to captivity with a trail of food.

The statues, made by Julian Warren in 2016, depict the animals in weird and wonderful positions.

You can find two perched on top of poles at the Cantock Steps, one watching passers by on Burlington Road, and another solving a Rubix cube outside Clifton Down station.

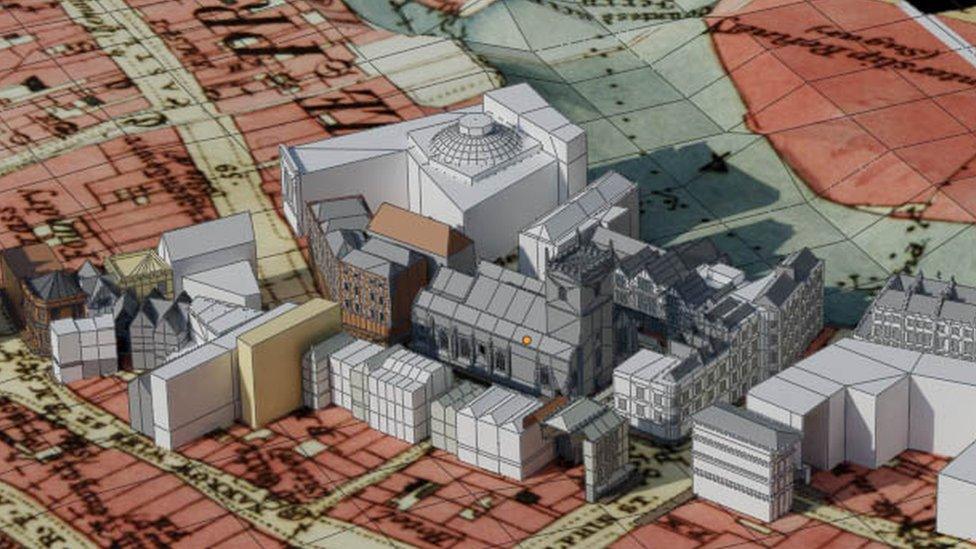

The stone frontage was reinforced by concrete beams to prevent leaning or collapse

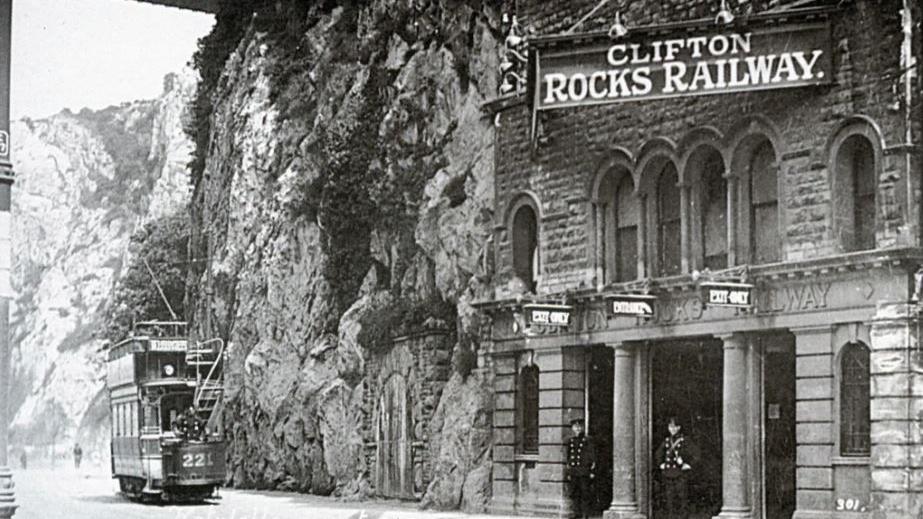

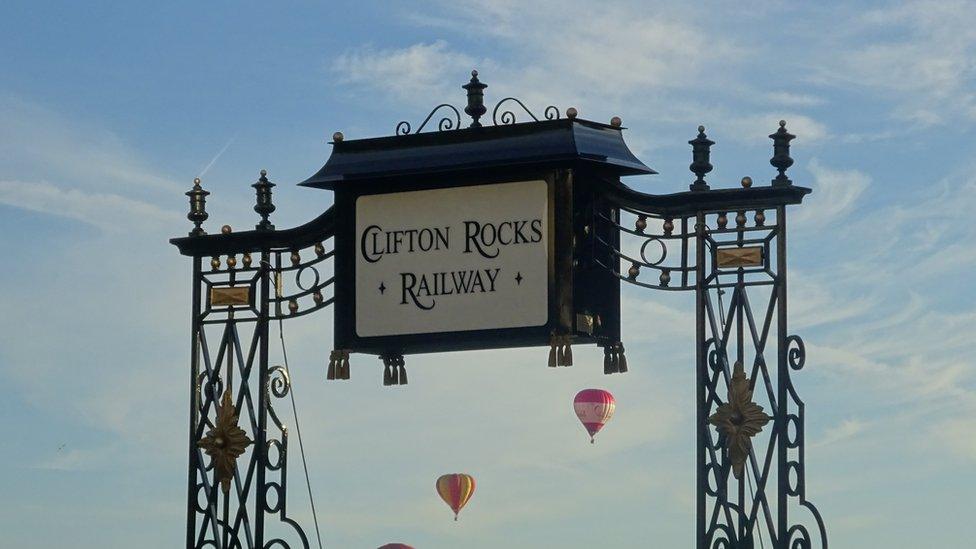

The majority of people driving along the Portway are likely to be glancing up at Bristol's pride and joy- the Clifton Suspension Bridge, while also trying to keep eyes on the road.

But if you take a second to look closer at the Avon Gorge cliffs, you'll discover the secrets carved into the limestone.

The Clifton Rocks Railway began operating in 1893, tunnelling 450ft underground to connect Clifton with the tramway and ferry station at the bottom of the hill.

During its first year, the funicular railway carried close to half a million passengers, but its popularity steadily declined until its closure in 1934.

At the time of construction, the railway tunnel was the widest of its kind in the world

During World War Two, the British Overseas Airways Company rented the top portion of the railway as storage space for barrage balloons that would be used throughout the conflict.

Air raid shelters were constructed below for employees and the general public, while the BBC set up camp in the lower section of the railway tunnel, in need of a secret broadcasting base that would be safe from bombings.

Over the last 19 years, a group of volunteers have been working to restore parts of the tunnel and open it as a museum for visitors.

Follow BBC Bristol on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to us on email or via WhatsApp on 0800 313 4630.

Related topics

- Published30 April 2019

- Published23 March 2021

- Published30 August 2022

- Published7 August 2022