Wales plans to remove profit from children's care

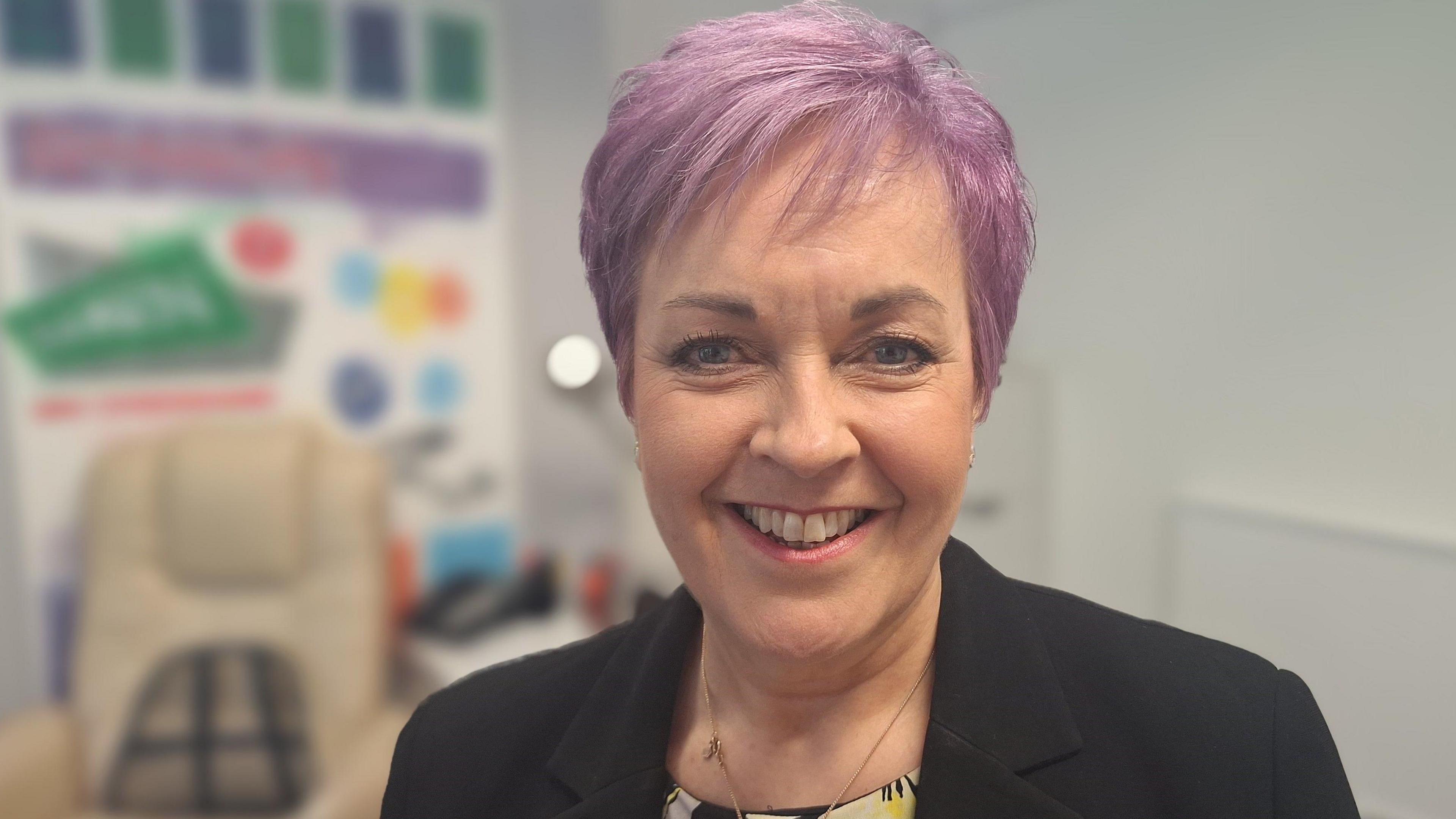

Georgia Toman said she felt "exploited" by private companies making profit from "traumatised and scared" young people

- Published

Wales is the first UK country with plans to remove profit from both residential and foster care for children.

Young people said they felt "exploited" when private companies made money from them.

They said they were relieved at the proposals in the Health and Social Care Bill (Wales), published on Monday.

Councils supported the idea but said they did not have enough resources to make the vision a reality.

Austerity contributing to rise in kids in care - judge

- Published29 January 2024

If children are taken into care, councils can commission private residential or foster carers to look after them.

Georgia Toman, 21, spent time living in both private and council run care placements.

She said money allocated towards placements should be spent on young people and not go "into the pockets of people who are far removed from it".

“[I feel] exploited because we’re being taken into a system where we’ve got people making money off the fact we’re traumatized and scared and in a situation that no one wants to be in,” she said.

Georgia, a student in south Wales, said it was "a relief" the Welsh government had published the bill and she hoped other young people "won’t be exploited in the same way".

She is one of a number of young people at the charity Voices From Care Cymru who have campaigned on the issue.

Voices From Care Cymru has campaigned for the removal of profit from children's care

Elliott James, 15, lives in a private children's home.

He said it was "upsetting" that private providers made a profit from the care system.

He is one of 7,210 children in care in Wales, a number that has risen by 25% over the last ten years.

The increase in children in care has meant the number of children’s homes has followed suit.

In 2020, there were 204 children’s homes in Wales, but now there are 314.

Three quarters are run by private companies.

Elliott said he wanted profit to be removed to improve care for young people.

“We want to make it better for them so that they don’t have the same experience as we did,” he added.

Most children in care live with foster carers and a third of those live with relatives or friends – known as kinship care.

Scotland and Northern Ireland do not allow for-profit companies to run foster care agencies, but do allow private companies to run residential homes.

The Welsh minister for social care, Dawn Bowden MS, said there had been a proliferation of private providers coming into the market

Dawn Bowden MS, the minster for social care, said young people had been "marketised" and huge profits had been made.

“We’ve heard the private sector can make profit from anything up to 23%,” she said.

She said the cost of residential care had risen from £65m in 2017-18 to £200m this year.

The cost could rise to nearly £1bn within 10 years if nothing was done, she said.

Ms Bowden said the Welsh government was also working towards reducing the number of children in care.

“We need to work with local authorities and the sector to find a better way of delivering what we know is hugely important to children, many of whom are coming from very traumatic backgrounds," she said.

Quarter of care leavers homeless by 18 in Wales

- Published24 May 2023

Councils said they supported the idea and that removing profit was the "right thing to do".

However, the Association of Directors of Social Services Cymru (ADSS) said more funding was "desperately needed" to make the vision a reality.

Lance Carver, the chair of ADSS Cymru, said councils also needed more time and the needs of the child should be central to the process.

“We have to acquire homes, kit them out, make sure we have staff and provision to provide the service,” he said.

“Homes need to register with Care Inspectorate Wales so it requires a significant amount of investment in order to get that off the ground and to keep it running.”

He said more children could go into care as an "unintended consequence" of the change in law, because councils would have to spend more time on redesigning residential provision.

“With limited resources we will have less time to focus on supporting those families at an earlier stage where we would potentially prevent the need for their children to come into our care,” he added.

The Children's Homes Association has been asked to comment.

Related topics

- Published27 February 2020