Why didn’t police prosecute 'brutal' abuser linked to Church of England?

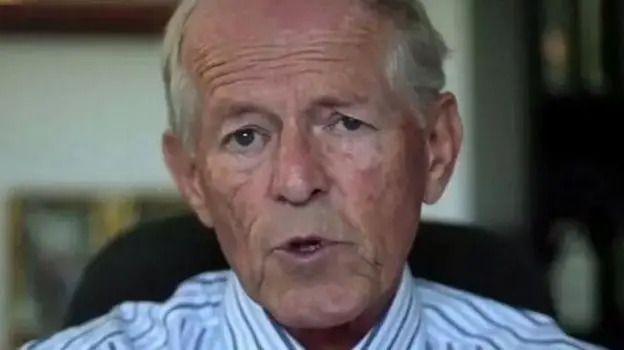

The Makin report found John Smyth was a prolific abuser of children and young men

- Published

John Smyth’s death in 2018 meant an "appalling abuser" associated with the Church of England escaped justice for crimes stretching back decades.

Smyth used his role in a Christian charity to assault over 100 children and young men - and the Archbishop of Canterbury resigned after being criticised in a scathing report earlier this month.

Now, an advocate for the victims of John Smyth tells the BBC the police were not "sufficiently curious" when told about him.

When a full investigation was finally launched it was nearly four years after officers had first known about Smyth, and only after reporting by Channel 4 News.

Keith Makin, the author of the Smyth review, has suggested police may have been "overwhelmed" by historical allegations of abuse in other cases, following the Jimmy Savile affair.

A spokesperson for the National Police Chiefs Council acknowledged officers faced "resourcing challenges" from an unprecedented number of cases.

So why did "the most prolific serial abuser to be associated with the Church of England", as the report described Smyth, avoid prosecution?

Archbishop of Canterbury resigns over Church abuse scandal

- Published12 November 2024

Abuse scandal is tip of the iceberg - campaigner

- Published13 November 2024

For over 30 years police were not told about Smyth’s crimes because of an "active cover up" inside the Church of England, according to the Makin review published earlier this month.

It found that Smyth was an "appalling abuser of children and young men. His abuse was prolific, brutal and horrific".

It also highlighted how evidence of crimes had been gathered in the 1980s but was suppressed, including details of children being physically and sexually abused.

"The scale and severity of the practice was horrific," noted the so-called Ruston report, named after the Rev Mark Ruston, who compiled it in 1982.

It listed victims being beaten hundreds of times with canes until they bled.

People inside the Church of England kept this secret, meaning Smyth was able to move to southern Africa and continue his abuse, the report found.

He was put on trial there for culpable homicide after the suspicious death of a 16-year-old boy in Zimbabwe but the case collapsed.

When were UK police informed?

It was only in the summer of 2013 when British police were first alerted.

One of his victims had asked the Bishop of Ely’s safeguarding adviser for counselling. Some details were passed to Cambridgeshire police relating to the case and that of another alleged victim.

According to the Makin review, the safeguarding adviser was told officers could do nothing: Smyth’s actions were "an abuse of trust" but they would be "unlikely to reach the threshold for a criminal investigation".

A spokesperson for Cambridgeshire Police told the BBC: "With the limited information available at the time, and the victims' not wishing to make a complaint, it was not possible for us to pursue an investigation."

Ely diocese was advised to contact police in Hampshire, where most of the alleged offences took place, and was told an intelligence report had been sent by Cambridgeshire Police to colleagues in Hampshire, although the Makin review found no record.

Hampshire Police told the BBC they first received a report of abuse in October 2014. . It was initially handled on their behalf by officers from the Met police.

They were given a summary of abuse allegations by a representative of the Titus Trust - the successor charity to the one running the summer camps where abuse had taken place.

But police did not know the identity of the alleged victims. A spokesperson from Hampshire Police told the BBC they asked for details but "the third party declined to provide these, stating that the victims would contact police."

The Titus Trust disputes this and say they had been told by Met officers not to include the names of victims when they gave an oral report to the police.

The failure of officers to then have direct contact with victims was ”a critical and important missed opportunity”, according to those who spoke to the Makin review.

"The matter was filed pending any new information coming to light," a spokesperson from Hampshire police told the BBC.

Justin Welby resigned as the Archbishop of Canterbury following criticism in the Makin report

When new information did come to light it was in a different police force area.

In late 2016 Thames Valley police were contacted by the Oxford diocese, who disclosed a full copy of the Ruston report, which was compiled more than 30 years earlier and which spelt out in graphic detail the beatings administered by Smyth.

Finally officers had it.

And yet still very little happened.

The report contained no evidence of crime in the Thames Valley area, so the force passed the information to national policing colleagues working on Operation Hydrant. This was set up in 2014 to coordinate the policing by forces around the country of historical child sexual abuse allegations, prompted by the Jimmy Savile case.

There'd been a "surge in adults reporting being sexually abused as a child", a spokesperson for the National Police Chiefs' Council (NPCC) told the BBC.

"It quickly became apparent that there was a real potential for duplication for forces as victims were reporting multiple offenders across different geographical areas."

The NPCC confirmed Operation Hydrant had received Smyth referrals and said information was shared appropriately with relevant police forces.

The Makin Review raised questions about the police’s overall handling of the reports it had received in this period and the failure to follow up on them. "An explanation offered by those in touch with police at the time suggests they may have been overwhelmed in this period by historic allegations of abuse."

The NPCC acknowledge "police forces up and down the country saw a massive increase in non-recent reports of child sexual abuse during this period which did present resourcing challenges for many".

When did police start investigating?

In 2017 police finally launched an investigation - Operation Cubic - but only after press reporting.

Channel 4 News had been tipped off about the Ruston report by Smyth survivor advocate and writer Andrew Graystone.

He hoped the press would push the police into action.

"They were too busy with Jimmy Savile and other victims," says Mr Graystone.

"They should have been more assiduous in following up whether victims they did know about had been contacted and therefore had had the opportunity to respond.

"They were not sufficiently curious as to whether there was more they weren't being told or whether the offences were more widespread and serious."

He says the consequence was further delay in dealing with Smyth. When the full scale of his crimes was finally made public it was too late.

In 2018 the Crown Prosecution Service agreed there was a case for him to answer and arrangements were begun to bring him back to the UK from South Africa for questioning but in August he died.

"While the victims will not see the suspect charged and the allegations put before a court," said a spokesperson for Hampshire police, "we hope that the updates provided to them during the course of the investigation provided some reassurance that their allegations were taken seriously."

The NPCC said: "In the past many victims have been failed. This is not good enough and policing has worked hard to learn from its mistakes.

"The approach today to tackling child sexual abuse and exploitation has evolved and is much improved in many aspects. However, there is still much to do, and making these improvements is a significant priority for national policing."

Update 20 November: This article has been amended to include the position of the Titus Trust on the abuse allegations it handled.

Newsnight - Fall of an Archbishop

With Justin Welby stepping down as Archbishop of Canterbury, following criticism of his handling of a report into a prolific child abuser with ties to the Church of England, Victoria Derbyshire asks a senior bishop if he should have gone sooner.

- Published13 November 2024

- Published12 November 2024

- Published7 November 2024