Safety records falsified after mining disaster on display

Gresford colliery in the aftermath of the explosion

- Published

Documents showing safety records were falsified after a mine disaster which killed 266 people have been on display in Wrexham.

They were among a host of exhibits marking the anniversary of the Gresford Colliery tragedy in 1934.

It's the first time the National Archives has offered to share original documents with a community.

The records were altered to cover up poor safety practices at the mine.

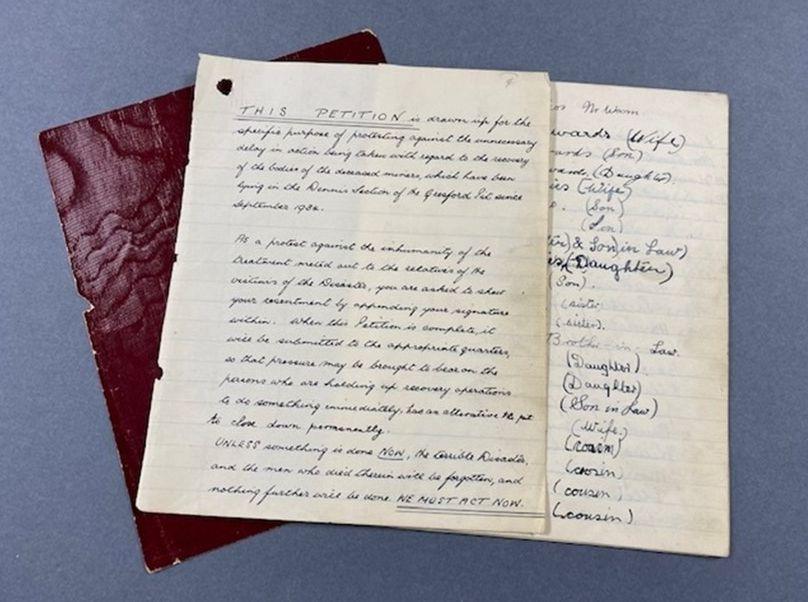

A petition calling on the authorities to recover the bodies of the dead

It is not known what caused the blast in the early hours of 22 September 1934 but poor maintenance and mismanagement were said to be factors.

During the Great Depression mine owners were desperate to increase production, and were put under pressure to maintain coal output at the expense of maintenance or "non-productive" work, the documents show.

Sarah Castagnetti from the National Archives learned about the disaster from the Welcome to Wrexham documentary

The documents were uncovered at the National Archives in Kew, London, after visual collections specialist Sarah Castagnetti learned about Gresford's history in the Welcome to Wrexham documentary.

She said: "I would not be so presumptuous as to come here and tell the story of the Gresford disaster.

"So we've been really privileged to work with other people here who have been working their whole lives to keep these memories alive."

Among the artefacts is a petition calling on the authorities to recover the bodies of the dead. Most never were.

Ms Castagnetti said: "I saw these little red notebooks and they were full of all these signatures, this petition from the community.

"And it really brings you to that moment and to what those people were going through is just such a personal piece of evidence."

Wrexham mark Gresford Colliery disaster

- Attribution

- Published22 September

Mining disaster relatives help keep heritage alive

- Published28 January

Opera world premiere marks pit tragedy anniversary

- Published26 July 2024

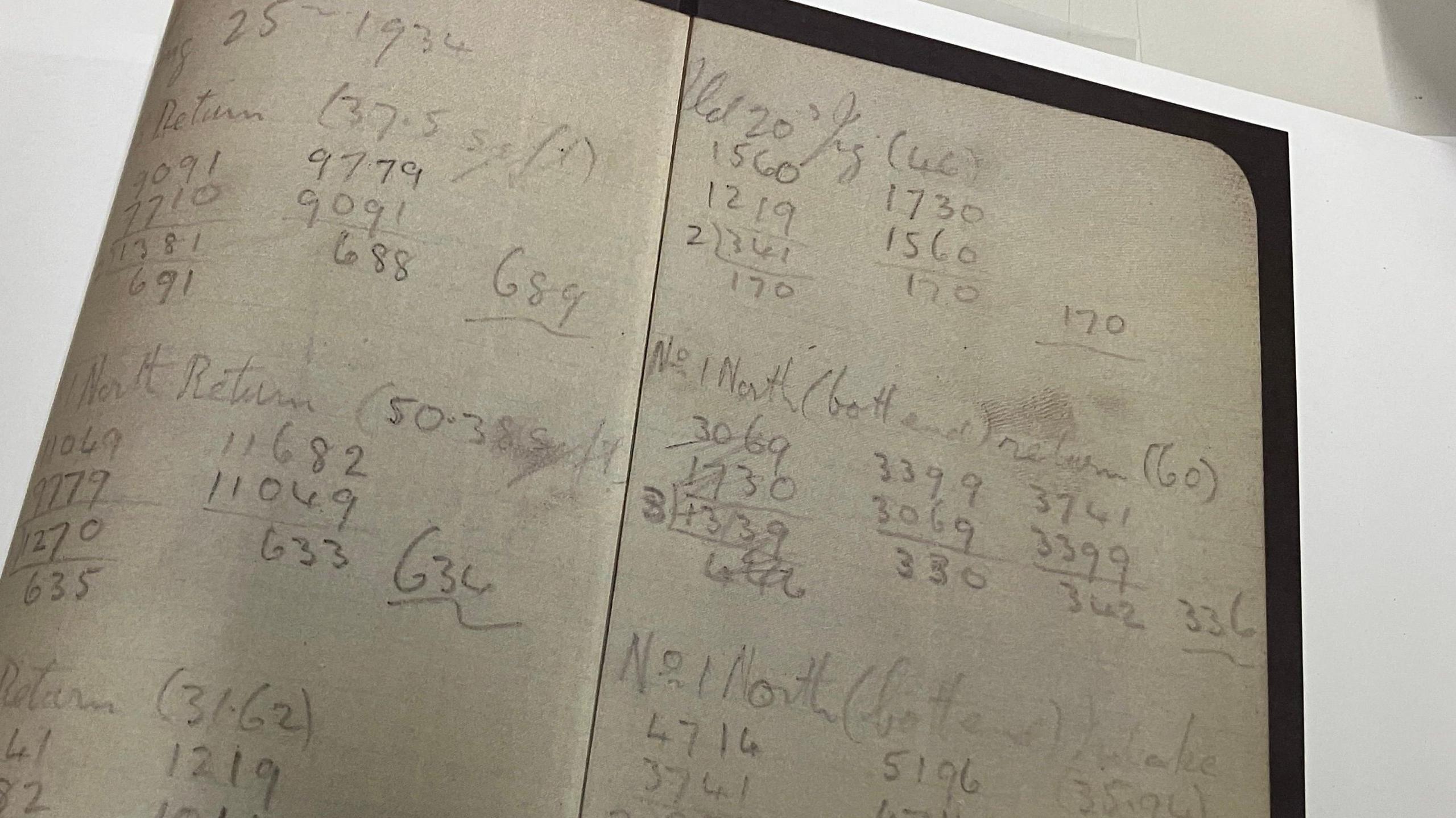

A notebook was also found showing good air quality readings from the mine in the months before the blast.

Surveyor William Cuffin later admitted he had falsified them at the behest of the mine manager to avoid scrutiny over lax health and safety.

William Cuffin's notebook with false air quality readings is part of the exhibition

Alan Jones' grandfather swapped shifts with his cousin Jabez Jones on the night of the explosion to watch the football. Jabez was one of those killed.

Mr Jones said: "At that time Wrexham were playing Tranmere Rovers and he was desperate to go to the game, so he changed shifts with Jabez Jones and unfortunately he still lies with 252 others entombed underground."

Despite Mr Jones' intimate connection to the disaster the detail in the archive material came as a shock.

He said: "All the hairs were up on the back of my neck, I can promise you that. I just didn't know they existed. I was astonished at what they'd got there.

"In my mind, it was just government documents. I didn't realise they'd collected everything regarding the inquiry, petitions. It was remarkable."

Alan Jones worked at Gresford in 1960s and lost a relative in the tragedy

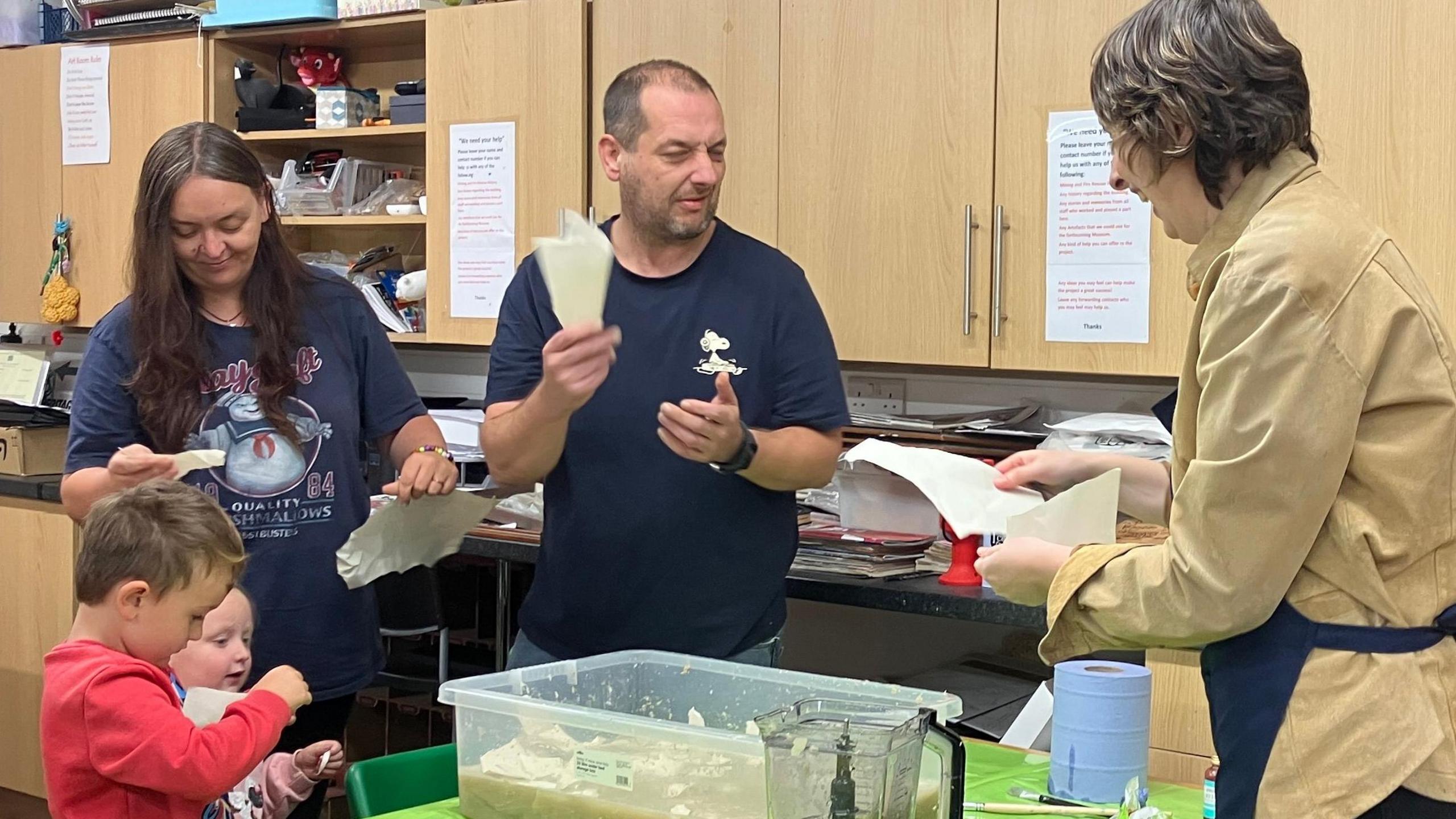

The National Archives organised a family day at the Wrexham Miner's Project explaining how they collated all the Gresford material and teaching people how to preserve their own histories for future generations.

Natalie Brown from the National Archives said: "A box that isn't airtight, that's clean, can do a world of wonders.

"Keeping things in a stable environment, taking things out of the attic, out of the basement, into the main part of the house, that's really helpful.

"And an object without a story is sort of out of context. So really record those stories and the meanings, like who's in the photos, what was happening on the day, that's really important."

Natalie Brown hosts a paper making demonstration at the family day in Wrexham

"Telling stories is an act of conservation. It's an act of preservation for the object but for the person it's an act of care.

"My job really allows that: to bring out the stories, to work with communities to understand those personal stories."