How to avoid a puncture on the Moon

The Apollo mission lunar rovers were lightweight vehicles

- Published

Going back to the Moon after half a century, and then to Mars, literally means reinventing the wheel.

After all, Mars is a long way to come back if you get a flat.

"One thing you cannot have is a puncture," says Florent Menegaux, chief executive of the French tyre-maker Michelin.

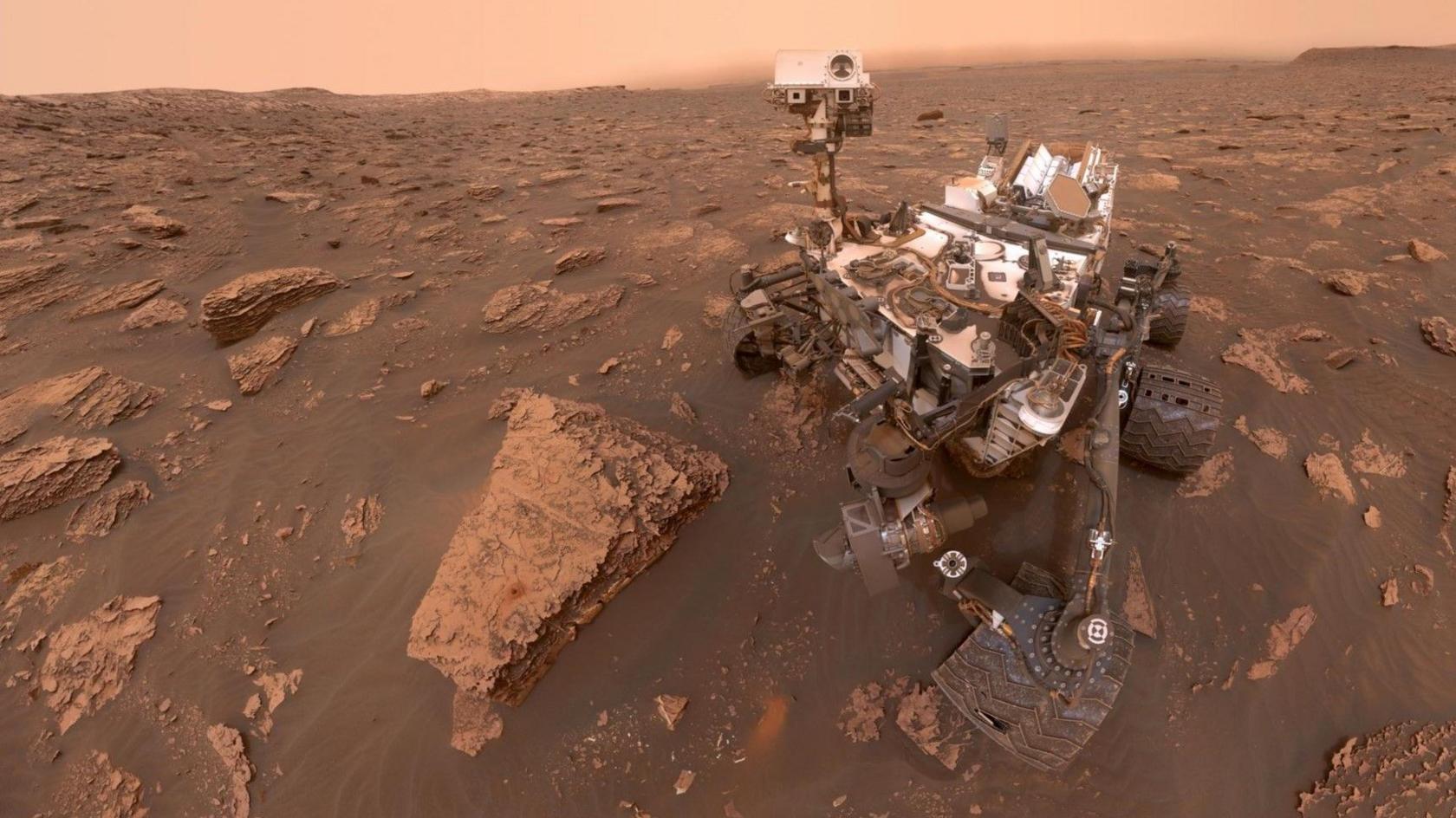

The tough conditions on Mars have been underlined by the experience of the unmanned Curiosity rover.

Just a year after landing in 2012, its six rigid aluminium tyres were visibly ripped through with punctures and tears.

As for the Moon, the US Artemis missions aim to return astronauts there, perhaps by 2027.

Later Artemis missions plan to use a lunar rover to explore the Moon's south pole starting with Artemis V, currently scheduled for 2030.

The Artemis astronauts will be driving much further than their Apollo forebears, who in six landings between 1969 and 1972 never ventured more than 25 miles (40km) across the Moon's surface.

"The target is to cover 10,000 kilometres in 10 years," says Sylvain Barthet, who runs Michelin's lunar airless wheel programme in the central French town of Clermont Ferrand.

"We're not talking about short, week-long durations, we're talking about decades of utilisation," says Dr Santo Padula, who has a PhD in materials science, and works for Nasa as an engineer at the John Glenn Research Centre in Cleveland, Ohio.

The rocky surface on Mars has damaged Curiosity's tyres

One big challenge for anyone developing technology for the Moon are the huge temperature ranges.

At the lunar poles temperatures can plunge lower than -230C, that's not far off absolute zero, where atoms stop moving.

And that's a problem for tyres.

"Without atom motion you have a hard time having the material be able to deform and return," says Dr Padula.

The tyres need to be able to deform as they go over rocks and then ping back to their original shape.

"If we permanently deform a tyre, it doesn't roll efficiently, and we have issues with power loss," says Dr Padula.

The new wheels will also carry much bigger loads than the lightweight rovers Apollo astronauts cruised around in.

The next space missions will need to drive round "bigger science platforms and mobile habitats that get larger and larger", he says.

And that will be an even heftier problem on Mars, where gravity is double that on the Moon.

Michelin uses high-performance plastics for its Moon tyres

Apollo's lunar rovers used tyres made from zinc-coated piano wire in a woven mesh, with a range of around 21 miles.

Since extreme temperatures and cosmic rays break down rubber or turn it to a brittle glass, metal alloys and high-performance plastic are chief contenders for airless space tyres.

"In general, metallic or carbon fibre-based materials are used for these wheels," says Pietro Baglion, team leader of the European Space Agency's (ESA) Rosalind Franklin Mission, which aims to send its own rover to Mars by 2028.

One promising material is nitinol, an alloy of nickel and titanium.

"Fuse these and it makes a rubber-acting metal that can bend all these different ways, and it will always stretch back to its original shape, says Earl Patrick Cole, chief executive of The Smart Tire Company.

He calls nitinol's flexible properties "one of the craziest things you will ever see".

Nitinol is a potentially "revolutionary" material says Dr Padula, because the alloy also absorbs and releases energy as it changes states. It may even have solutions to heating and refrigeration, he says.

However, Mr Barthet at Michelin thinks that a material closer to a high-performance plastic will be more suitable for tyres that need to cover long distances on the Moon.

The pads on the Bridgestone tyre mimic camel hooves

Bridgestone has meanwhile taken a bio-mimicry approach, by making a model of the footpads of camels.

Camels have soft, fatty footpads that disperse their weight on to a wider surface area, keeping their feet from sinking into loose sandy soil.

Inspired by that, Bridgestone is using a felt-like material for its tread, while the wheel comprises thin metal spokes that can flex.

The flexing divides the lunar module's weight into a larger contact area, so it can drive without getting stuck in the fragments of rock and dust on the Moon's surface.

Michelin and Bridgestone are each part of different consortiums that, along with California's Venturi Astrolab, are presenting their proposed tyre tech to Nasa at the John Glenn Centre this month (May).

Nasa is expected to make a decision later this year - it might choose one proposal or adopt elements of several of them.

Meanwhile, Michelin is testing its tyres by driving a sample rover around on a volcano near Clermont, whose powdery terrain resembles the Moon's surface.

Bridgestone is doing the same on western Japan's Tottori Sand Dunes.

ESA is also exploring the possibility of whether Europe might make a rover on its own for other missions, says Mr Barthet.

The work might have some useful applications here on Earth.

While working on his doctorate at the University of Southern California, Dr Cole joined a Nasa entrepreneurial programme to work on commercialising some of the technology from the Mars super-elastic rover tyre.

An early product this year will be nickel-titanium bicycle tyres.

Priced around $150 (£120) each, the tyres are much more expensive than regular ones, but would be extremely durable.

He also plans to work this year on durable tyres for motorbikes, aimed at areas with rough roads.

For all this, his "dream" remains to play a part in humanity's return to the Moon.

"So, I can tell my kids, look up there on the Moon," he says. "Daddy's tyres are up there."

More Technology of Business

- Published25 April

- Published11 April

- Published15 April