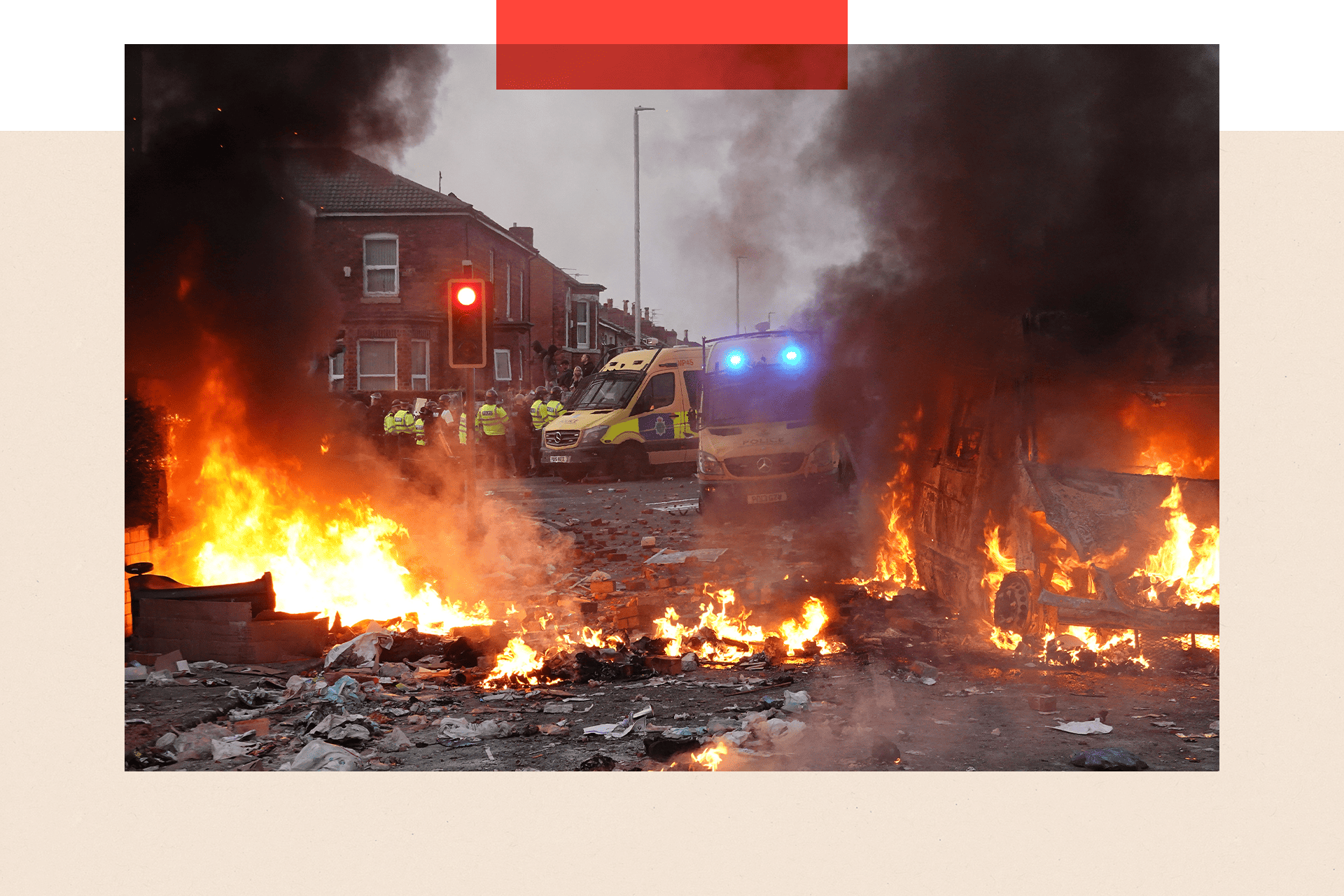

In Sunderland on Friday night, I watched a wave of criminality and thuggery engulf a proud city.

As they had done previously in Southport, Hartlepool and London, far-right activists - who claimed to be protesting at the murder of three little girls - attacked police trying to keep the peace. They set fire to an advice centre next door to a police station, threw stones at a mosque and looted shops.

But as well as the masked thugs hurling missiles at the lines of riot police, there were families in England tops cheering them on. I saw mums and dads pushing babies in pushchairs; small children draped in the St George’s flag joining the march.

One woman advised her son who was throwing stones at riot police to make sure he didn’t hurt himself.

Some, like Nigel Farage, the leader of Reform UK, have suggested what we are seeing is evidence of a country close to boiling over, community relations on the edge.

Is he right? Are we set for a summer of racial strife, with mosques hunkering down, police preparing for the worst and deepening community tensions?

Or are those who suggest the country is at breaking point at odds with statistics that reveal a different story, one where compared with a generation ago, Britain is a low-crime and socially tolerant nation?

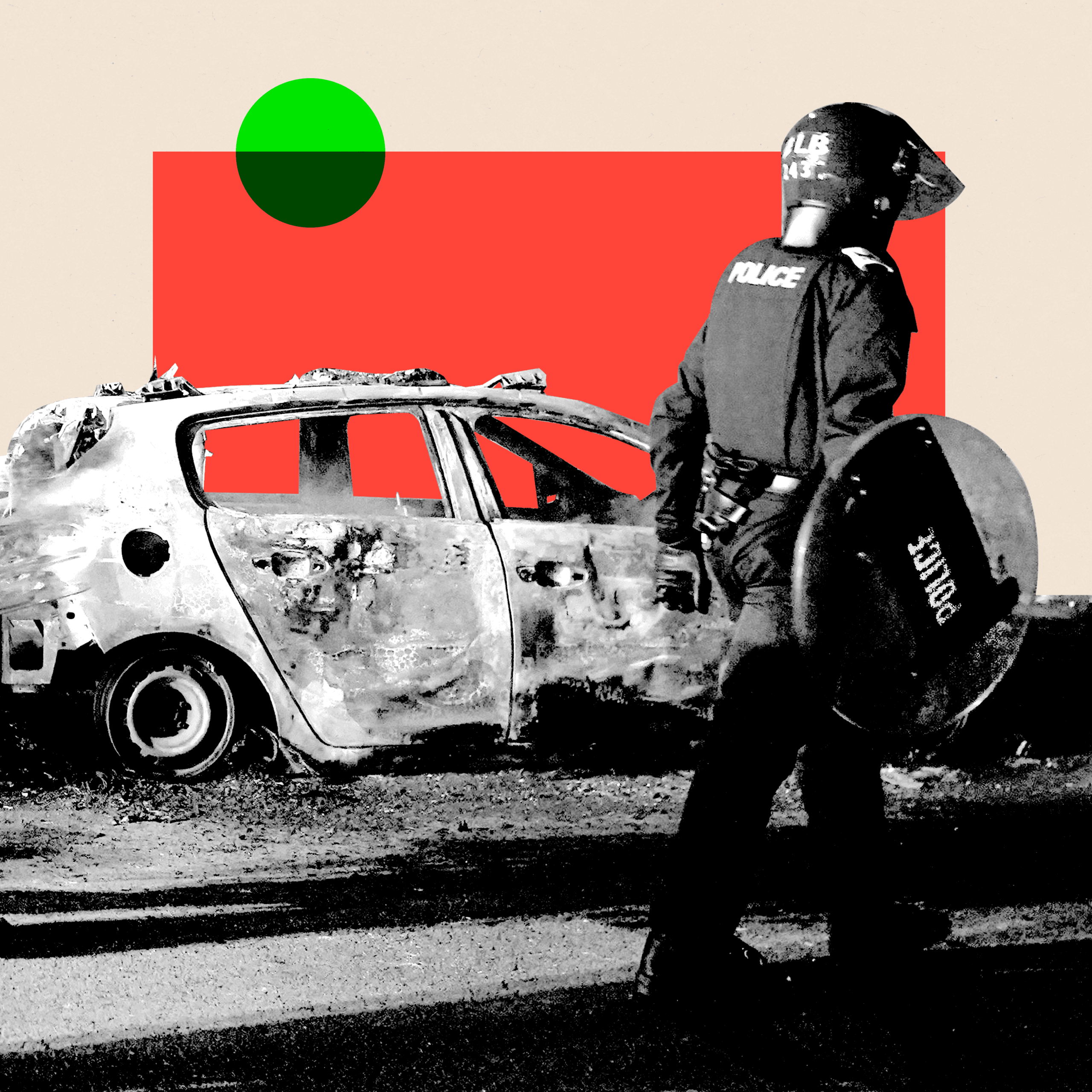

Police first came under attack in Southport when a protest following the attack in the town turned violent

The spreading of lies and misinformation led by far-right extremists after the killings in Southport, is an example of their wider tactics. In Southport, they focused on the false claim that the person responsible for the attack was a Muslim asylum seeker who had arrived in the UK by boat.

More broadly, misinformation has also been spread that wrongly suggests levels of immigration and violent crime are linked, and incorrect claims have been made that foreigners, notably Muslims, present a particular threat to children. Police and politicians are accused of failing to protect those who view themselves as the indigenous population.

Often, unevidenced claims of “two-tier policing” - that senior officers are more lenient towards ethnic minorities when they protest - are also promoted by far-right activists on social media.

“What will it take for you to be angry enough to do something about this?” asked Tommy Robinson, the former leader of the far-right English Defence League.

It is a compelling narrative to those looking for someone to blame for the struggles they face in their daily lives: the cost of living, unaffordable housing and poor-quality public services.

Rioting leaves scars on communities that already struggle with economic challenges. But visit the day after and you see a very different Britain.

After disturbances in Hartlepool last week, I went to the Salaam community centre on the street which had been targeted during the disorder on Wednesday night. The building had become the headquarters for a volunteer clean-up.

The community centre regularly delivers food parcels and other supplies to those struggling to make ends meet. Time after time people from a range of backgrounds came up to me to say the idea that the town was a racial tinderbox was ridiculous. They spoke of a close-knit community in which people from all backgrounds looked out for each other.

Work begins to ID Holiday Inn petrol bomb rioters

- Published5 August 2024

Watch: Violent crowds hurl missiles, set fires and target hotels

- Published4 August 2024

As if to prove the point, a group of young women arrived having just delivered chocolates and other gifts to the police station to thank the officers who had had to deal with the trouble. They were carrying packs of food and drink to be distributed to local families caught up in the violence.

A local butcher had become a Hartlepool hero for staying in his shop as the mob attempted to smash his windows, protecting his meat knives and cleavers from falling into the wrong hands.

An asylum seeker who was punched as he walked down the road during the disorder was the next day having his hand shaken by people from the many different communities which make up this deprived neighbourhood.

“Tight as a drum”, was how the local beat bobby described the people on his patch. “There’s a few idiots but I know everyone round here and most of the adults out on the street were not from Hartlepool.”

To suggest there are no tensions in the town or others affected by recent disorder would be wrong. The rhetoric of the far-right is effective because it taps into genuine frustration and disaffection.

Race relations in Hartlepool were sorely tested last year when an asylum seeker, Ahmed Alid, stabbed a pensioner to death in the town. Alid, who said he was motivated by events in Gaza, was jailed for life in May, with a minimum term of 44 years.

Beyond these relatively isolated incidents, there are, of course, legitimate concerns about the impact high levels of immigration can have on communities where healthcare and schools are under pressure. There are also questions about the effect on community cohesion.

Home Secretary Yvette Cooper has said rioters will "pay the price" for their actions

The evidence shows there is significant worry around both current levels of legal and illegal immigration. An Ipsos survey in February, external found 52% of people believed current immigration levels to be too high. Two years earlier, only 42% said that.

But the Ipsos survey showed people are generally more positive about the impact of immigration than not, although that gap has tightened since 2022 too.

As for longer term attitudes, the respected European Social Survey found that in 2022, external most people in the UK thought immigration had been good for the economy and the country’s cultural life. A clear majority said it had made Britain a better place to live.

Separate research by the World Values Survey, external found the UK the least likely country to agree that immigration causes crime or unemployment. Just 5% of Brits said they’d be unhappy to have an immigrant for a neighbour, one of the lowest proportions found anywhere.

Some areas that have seen protests, such as Middlesbrough, have crime rates significantly above the national average. And with policing facing well-documented challenges and backlogs in the courts, people don’t necessarily feel like the police or courts are dealing with things. This sense may be particularly acute in areas with the highest crime rates.

But the best evidence available from the Office for National Statistics suggests crime is a fraction of what it was a generation ago. For every five crimes in England and Wales in 1995, there is just one offence committed today., external

Anti-social behaviour is also at a record low. Your chances of being a victim of violence in Britain are almost certainly lower today than at any time in history. The figures show that over a time when migration has been rising, violent crime has been falling.

Presented with a daily array of terrible crime stories, we can be forgiven for imagining the country is becoming more lawless and more dangerous. But when you ask people about their experiences of crime, it is the opposite according to responses to the Crime Survey of England and Wales.

In Sunderland, it looked like quite a few saw the unrest as a bit of a Friday night spectacle, an opportunity to demonstrate their anger at a state they believe ignores them.

For others it was less spontaneous. Shortly before the trouble kicked off in the city centre, a train pulled into the station carrying passengers who had begun their journey that day in Glasgow, full of men draped in the union jack. Outside the station, they were greeted by a crowd with southern accents.

I noticed a few faces with links to the now defunct English Defence League - this is not the first time I’ve seen racial tensions flare in 45 years of covering the UK.

What is different this time is that self-publishing on social media means those seeking to whip up the mob can do so without worrying unduly about the facts. There is evidence of foreign-owned websites actively spreading disinformation which is lapped up and spread by extremists attached to an amorphous array of self-styled “patriot” groups.

For those seeing violence erupt in their community this is clearly a very worrying time and we don’t yet know whether we have seen the worst of it.

But I have watched the clean-up operation in Hartlepool and read the research that suggests Britain today is safer and more tolerant than it has ever been. Because of that my sense is that right now it would be a mistake to assume that orchestrated far-right hooliganism is representative of the mood in Britain.

More from InDepth

In one US state, women politicians dominate. What pointers can it offer Kamala Harris?

- Published3 August 2024

The junior doctors' strikes may be over. But is trouble ahead?

- Published2 August 2024

Why we might never know the truth about ultra-processed foods

- Published28 July 2024

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think - you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.

Get in touch

InDepth is the home for the best analysis from across BBC News. Tell us what you think.