What the India tariffs deal means for Scotch whisky

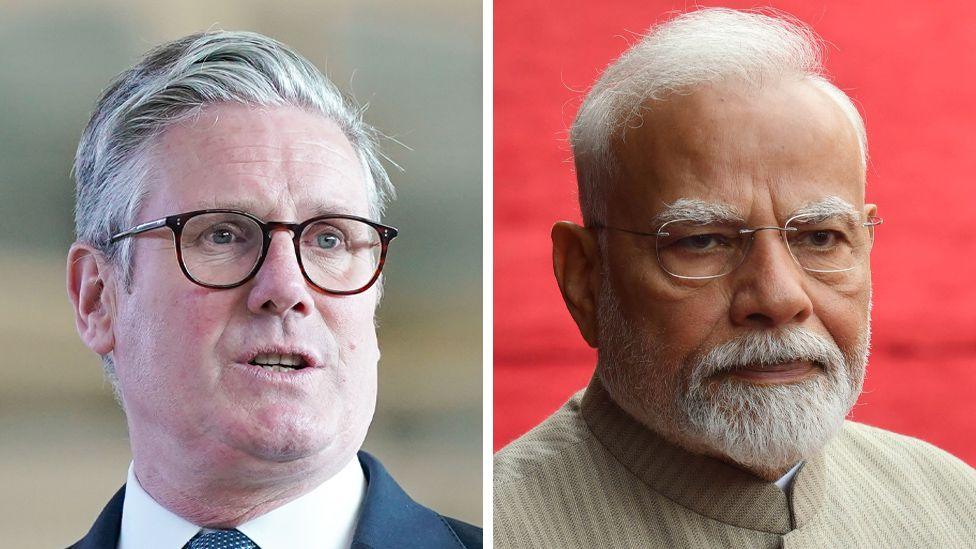

UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India shake hands after signing a free trade agreement at Chequers

- Published

The world's biggest whisky market has long been an enticing prospect for Scotch exporters, but was protected behind 150% tariffs.

It was symbolic of India's long-time attachment to developing its own industries behind high barriers to trade, believing that its huge population was a sufficient marketplace in which to develop its economy in its own way.

For more than 30 years, the trade barriers have been gradually dismantled.

Indians have learned that they have skills that can compete globally, notably in IT, pharma, back office processing, and increasingly in manufacturing.

It has slowly woken up to the benefits of further lowering obstacles to trade.

And as more people have joined India's middle class, by the hundreds of millions, they have put more pressure on their government to give them access to imported products.

Scotch whisky is one of them, successfully marketed as a signal of prosperity and an international, sophisticated outlook.

Despite having a 150% tariff and other non-tariff barriers, Indian imports of Scotch have grown to become the biggest national market by volume, overtaking France, while the USA is the biggest by value.

Much of India's imported Scotch is in bulk for blending with domestically-produced whiskies, which can be sold at a premium price.

Scotch whisky is successfully marketed as a signal of prosperity and an international, sophisticated outlook

The UK-India trade deal struck in early May and being signed between the countries' prime ministers at Chequers on Thursday cuts that tariff in half and then sees it cut to 40% within 10 years.

That's still a hefty tariff, while the average Indian tariff on imported UK goods falls from 15% to 3%, and most trade will have no tariffs at all. That includes soft drinks, down from a 33% tariff - an Irn Bru, sahib?

But it's a very significant boost to the prospects of selling more branded Scotch and pushing into premium markets for single malts.

What has made the difference that got this deal done?

One key to this has been Diageo. With around 40% of Scotch production, it has the brands and the marketing heft that already reach into India's middle class.

It has also been crucial to weakening the resistance to tariffs of India's domestic distillers, by becoming the largest of them.

It bought the United Distillers empire inherited and expanded by Vijay Mallya, the flamboyant businessman who paid big for Scotch distiller Whyte & Mackay.

As his empire collapsed and he hit big legal problems (still unresolved), Diageo took control in 2015, but had to offload Whyte & Mackay to avoid the attention of the competition regulator.

Thus, the company that is the main domestic distiller became the same company that is the biggest winner if tariffs come down.

Of course, a trade deal is a lot more complex than alcoholic spirits. And they have been less of a concern for the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. He comes from Gujarat, a state that has long banned consumption or sale of alcohol, with a few exceptions recently put in place.

He may reckon on continued Indian obstacles from non-tariff barriers, including labelling, customs delays, retail restrictions, and India's sclerotic legal system, but the trade deal has tried to secure gains on these.

Four things you need to know about UK-India trade deal

- Published24 July

Scottish exporters 'disappointed' over Trump tariffs

- Published3 April

One of Mr Modi's personal interests is in the global export of yoga – the Hindu version rather than its western interpretations.

And among the categories of workers given special measures in the trade deal are yoga teachers, as well as chefs.

India has other, more significant asks of the UK, which have also been a reason for previous British ministers to stall a deal.

Foremost among them has been access for its companies to place Indians into the British labour market. Companies such as Wipro and Tata Consulting Services have vast numbers of IT specialists they can place with clients, but Britain has resisted allowing more in.

Indian companies have invested in UK subsidiaries and bought British companies, such as Jaguar Land Rover. They also want to be able to place their own people from India in British factories and offices, at least temporarily.

The trade deal allows for a smoother process, and more predictable "locked-in" work visa rules, for longer periods than they've been able to secure before.

The UK government's description of that deal is defensive, emphasising what it will not do – it won't increase immigration figures, and it will not mean that these migrant workers will have the right to remain in Britain permanently.

Other parts of the trade deal extend to car trade in both directions, where India's reputation for car manufacturing has greatly improved under Japanese and Korean influence.

Food and clothing imports with low, or no, tariffs are expected to drive down some costs for British consumers.

Economic modelling

The total value of this is calculated by the UK government at £6bn of additional investment in the UK, as a stimulus to create 2200 British jobs over its initial 15 years and to add £4.5bn to total output, including a £190m gain to the Scottish economy.

The economic modelling suggests exports from the UK rising by more than £15bn over the projections for trade growth without a deal. In recent years, they've been worth around £11bn.

That's a big number, but not huge in terms of economic growth more widely. Its significance lies in being the biggest and most significant deal struck by the UK government since Brexit, when Westminster regained the power to strike deals on trade.

It sends a signal. India and the UK are open for business, and touting the gains from freer trade, rather than wanting to put up new barriers. The contrast is clear with the American president, arriving in Britain as Narendra Modi departs.

The Scotch whisky industry is very pleased by the India deal, but remains very concerned about the prospect of further barriers to sales in the USA. There is already a 10% tariff.

That could have a 25% added to it in July next year, with the end of the suspension of a tariff on single malt whisky, including the more valuable brands.

That was introduced as collateral penalty in the dispute over state subsidies for Boeing in the US and Airbus in the EU, with a reciprocal tariff on bourbon heading east, and it was then suspended while Joe Biden was president.

It does not require Donald Trump to impose that tariff once more. Unless he chooses to change it, it will automatically return next American Independence Day, 4 July.

Ahead of Sir Keir Starmer's meeting with the US President somewhere in the Aberdeen area, whisky industry source says "he must not be allowed to leave Scotland without an agreement to avoid that happening".

- Published6 May