Final goodbye to China's 're-education' camps?

- Published

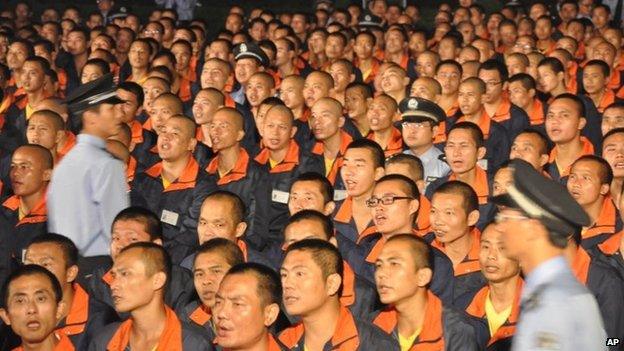

Some "re-education through labour" camps are to be converted to "drug rehabilitation centres"

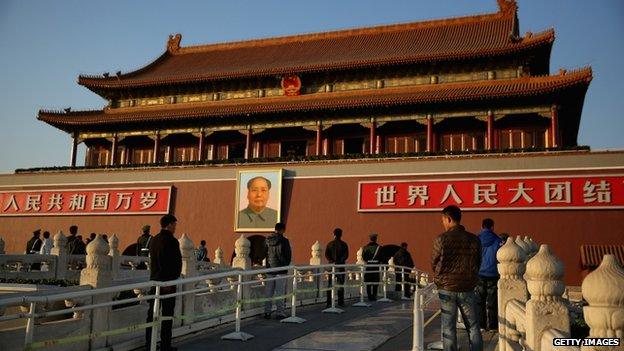

Many celebrated last week's announcement that China will abolish its much-hated "re-education through labour" system.

The system, which dates back to the 1950s, allowed the Chinese police to send anyone to prison for up to four years without a trial. A labour camp sentence was almost impossible to appeal.

"The re-education through labour system was arbitrary, it was abusive, it was unconstitutional," explains Nicholas Bequelin, a senior researcher with rights group Human Rights Watch.

He argues that the system's abolition opens the door for legal reform in China.

"There's no point in trying to improve the criminal law system, trying to decrease the incidents of torture, forced confessions and miscarriage of justice if the police can just go another route and send someone without any kind of procedure and due process for up to four years to a labour camp," Mr Bequelin says.

China had 260 labour camps holding 160,000 inmates at the start of this year, according to figures from the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights Watch.

But that number seems to be shrinking. The Shanghai government announced on Wednesday that it has already released all of the people held at its labour camps.

'Changing sign boards'

Still, some fear that the extra-legal camp system will disappear in name only.

Most of the people locked up under the re-education through labour system are detained for drug offenses - either selling or buying small quantities of illegal narcotics.

The police will still have other tools at their disposal even after "re-education" camps are abolished

At least one former labour camp in Yunnan province will be transformed into a drug rehabilitation centre, according to state-run Xinhua news agency. More camps in Sichuan and Guangdong provinces have also made the switch, according to Human Rights Watch.

"They're just changing the name of 're-education through labour camps' to 'drug rehabilitation centres'. They're just changing the sign boards," Mr Bequelin said.

The police will still have various tools at their disposal to deal with petitioners or dissidents, including so-called black jails, or extra-legal prisons, or the ability to dispatch detainees to psychiatric prisons without their consent.

Still, the abolition of the camp system reduces the power of China's police to act with impunity.

"One of the upshots of abolishing re-education through labour is it brings up the cost of repression by the government a little bit," Mr Bequelin said.

"It's just a little bit less easy and more costly in terms of public image to suppress ordinary citizens who have done nothing but to express their rights."

Beijing's next steps over the coming months will be crucial, explains prominent Shanghai lawyer, Si Weizhang. He is waiting for the leadership to release a proposed new "education and correction" law, which will probably give the police the power to detain people for a period of time.

"I predict people who commit minor crimes will still be detained from six months to a year. This is still quite a big range, just the labour camp system, on a smaller scale," he said.

"The creation of the new law should be transparent, to ensure the labour system isn't reintroduced in disguise."