Shock and anger after Kunming brutality

- Published

There is a profound outpouring of grief online following the shocking attack at Kunming station

There are many shocking things about the attack at Kunming station. The number of dead, 29, in just 12 short minutes of carnage. And the choice of weapons - swords and cleavers. The attack appears to have been chillingly calculated in its brutality.

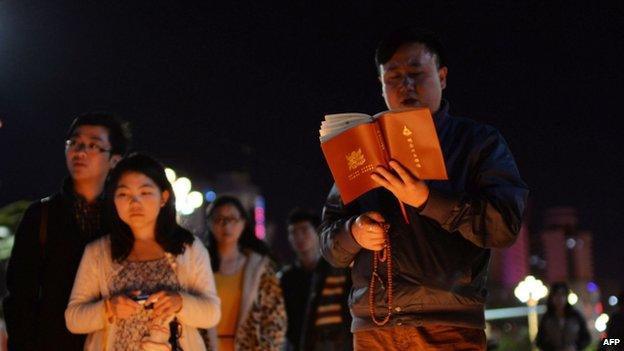

The sense of national outrage and grief, being expressed in the outpouring on China's internet, is profound. On the station concourse, a small memorial has been set up where people are laying flowers and lighting candles.

Xiang Feng You, who has come to the station to see his wife safely onto her train, breaks down when I ask him what he thinks about what has happened here. "It's terrible," he says. And then choking back the tears: "I can't speak, I'm sorry."

There is anger too. "I feel so shocked," Tan Zhuzhu tells me after placing her candle on the ground. "How could they hurt innocent people? What if they were their friends and family then how would they feel?" she asks.

'Bias is obvious'

It is shocking too how quickly Kunming station has retuned to normal. Within little more than 24 hours of the attack all traces of it had been removed, the blood cleaned from the floor and the concourse and ticket barriers opened.

The authorities appear to believe they have all the evidence they need to reach the speedy conclusion that separatists from Xinjiang were behind this attack.

Officials believe that separatists from Xinjiang were behind the attack which killed 29 people

No details, other than that broad claim, have been released. But if true, the attack would represent a dramatic escalation of China's simmering Uighur problem.

There have been hints at a radical, international dynamic for years, driven by Xinjiang's more open borders with Afghanistan, Pakistan and the former Soviet states with sizeable Turkic communities.

The Eastern Turkic Islamic Movement was placed on the US list of terrorist organisations in 2002. But so far the violence has been mainly confined to clashes between groups of Uighurs and the security forces inside Xinjiang.

China's harsh security crackdown has made it next to impossible for international journalists to report from Xinjiang and to assess the real strength of radical Islamist and separatist sentiment on the ground.

The consensus, at least up until now, has been that it is probably exaggerated by the Chinese government in order to justify the restrictions it places on Uighur religion, language and culture.

China bristles at such claims, accusing Western commentators, with their focus on Uighur rights, of hypocrisy and double standards on terrorism.

People set up a memorial near the station, leaving flowers and candles for those who died

In fact, even in the international media coverage this weekend, China has detected the same affront.

"It's clear that these Western media are hypocrites, and their callousness driven by bias is obvious," reads an editorial in Communist Party paper People's Daily.

"Aren't you talking about "human rights"? Have you seen those victims lying in a pool of blood? … If the same thing happens in the US, no matter what the casualty is, how will you comment on it, and are you still going to be stingy about using the term 'terrorist'?"

With the state-controlled Xinhua news agency describing the attack on Kunming as "China's 9/11" it seems likely that Beijing will intensify its argument that the threat is very much a real one.