Joshua Wong: 'We had no clear goals' in Hong Kong protests

- Published

Juliana Liu speaks to Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong about the future of the protest movement and his role in it

Wherever Joshua Wong goes in Hong Kong, the teenage political activist is instantly recognised.

In the space of just half an hour in the Admiralty district, two young professionals and a group of middle-aged women greet him warmly, asking to pose for photos with him on their mobile phones.

But when I ask for permission to snap them jointly for a news story, some well-wishers decline, saying they do not wish to be publicly identified with the democracy campaigner, fearing it might affect their jobs.

Mr Wong, 18, just smiles and poses. He is not surprised.

The expression of private but not public support may help explain why last year's Umbrella protest movement, while unprecedented in scope and length, did not ultimately succeed in gaining greater voting rights for Hong Kong citizens.

Mr Wong leads the high-profile Scholarism student activist group

"First, we did not have any clear goal or roadmap or route for democracy. We did not deliver the message to the general Hong Kong public," says the university student, over lunch.

"Secondly, not enough people were willing to pay the price by protesting. We did not have enough bargaining power with the Chinese authorities.

"Say, for example, during the Umbrella Movement, if two million Hong Kong people had occupied the streets, along with labour strikes, and if this had continued for more than two months, we would have had enough bargaining power."

Global icon

Tens of thousands of people took part in the 79-day movement, which ended in mid-December when the authorities dismantled the main occupation sites in the Admiralty, Causeway Bay and Mong Kok districts.

Mr Wong, already well-known in Hong Kong for successfully campaigning against the introduction of patriotic education in local schools, emerged as a global democracy icon.

In fact, the movement was unexpectedly sparked when he and other young activists scaled a high fence surrounding the forecourt of the central government office on 26 September.

Footage of the police arresting protesters, including Mr Wong, drew public anger and prompted pro-democracy supporters to rally.

The initial arrests of about 60 protesters including Mr Wong on 26 September sparked subsequent protests the next day

When the authorities cracked down on the growing crowd with tear gas, the public grew even more infuriated and took to the streets in one of the biggest mass protests Hong Kong had ever seen.

"My decision to climb over the barrier was the best decision I made in the whole of my life," he says, before sheepishly conceding that getting together with his girlfriend, Tiffany Chin, was actually his best call.

Images of tear gas fired on protesters triggered widespread anger in Hong Kong and led tens of thousands to take to the streets

Deported, attacked

He says he has not been changed by the experience. His priority now is to finish his studies - he is studying politics and public administration at a local university - and plans on getting a job after graduation, though he isn't sure what kind yet.

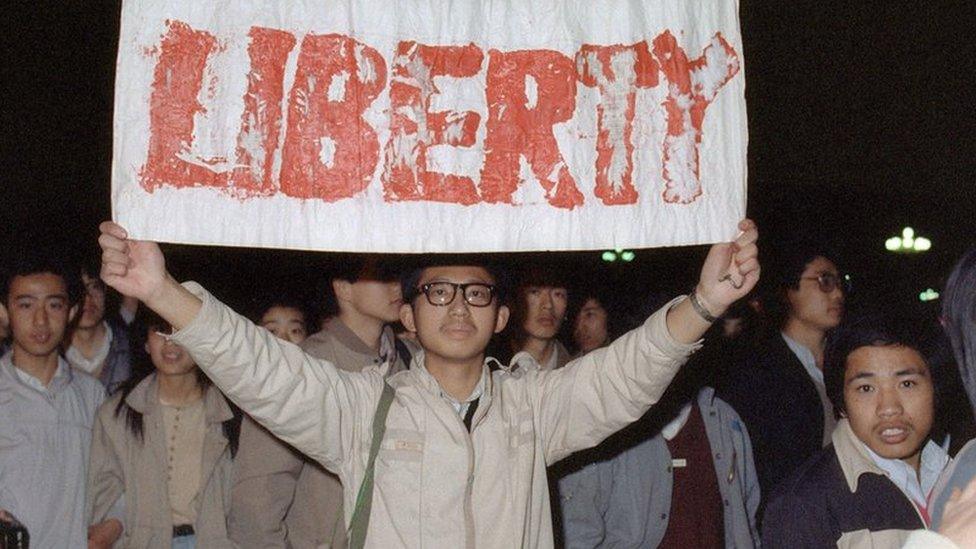

But in May, he was deported from Malaysia, after being invited there by local activists to talk about the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989.

In June, he and Ms Chin were beaten by an unknown man on the street after a movie date.

"Yes, I admit that I'm afraid," she wrote in a piece for a current affairs website after the attack. "Starting today, I feel a bit frightened every time my eyes meet someone else's on the street. This fear is unbearable, but I hope it won't last long."

Mr Wong keeps in constant contact with members of his student activist group

And in July, Mr Wong, along with other activists, were charged with obstructing police during a protest last year.

He denies having done anything wrong, but admits he faces jail time.

"In principle, I don't mind taking responsibility. I don't mind going to prison," he says. "But I don't know what I would do with no mobile phone and no internet. I think it would be utterly unbearable."

During the hours we spend together, he is constantly glued to his smartphone, tapping out messages on a chat group with more than 100 members of Scholarism, the protest group that he chairs.

They are hotly debating the future of democracy in Hong Kong in an opinion piece to be published by a local newspaper.

Road map

In June, lawmakers in the Hong Kong Legislative Council voted against a controversial proposal that would have let Hong Kong voters elect their chief executive - but only from a pool of candidates vetted by a pro-Beijing committee.

The proposal was rejected, which means that, in 2017, the city's top leader will again be chosen by a small committee largely loyal to the Communist Party.

But Mr Wong is looking far ahead. He wants to rectify the mistake of not presenting a viable plan to the public.

He says that by 2030, the democracy movement needs to present a clear roadmap spelling out how it can achieve a legally binding referendum on the city's future.

"Let every Hong Kong citizen vote to support a new Basic Law or constitution in Hong Kong. That, I think, is the minimum requirement," he says.

Mr Wong believes entering the forecourt of the central government offices on 26 September was one of his best decisions

By 2047, the "one country, two systems" formula is due to end, and the de facto border between the two sides is meant to disappear.

When asked whether he is planning another civil disobedience movement, Mr Wong says not for a few years.

"The power that we can mobilise on the street has already reached its maximum during the Umbrella Movement," he says.

"Maybe in 10 years, we'll be able to mobilise something much larger. But within these three to four years, we need to take a rest."

- Published18 June 2015

- Published11 December 2014

- Published12 December 2014

- Published25 June 2019

- Published2 October 2014