Taking stock of China's five year economic model

- Published

China's five year plan system is a Soviet-style throwback from China's communist past

Big changes lie in store for China in the next five years, as the government announces significant policy shifts in its new blueprint for the country. An end to the one-child policy, and a lowered GDP growth goal are the biggest changes to surface so far.

In the coming weeks and months, more details will emerge, explaining how the plan will be carried out and what objectives will be met. It's worth it to pay attention to the details.

The five year plan system is a Soviet-style throwback from China's Communist past, but it remains a pivotal feature of the Chinese government. We're just concluding the twelfth version of the plan.

Communist Party cadres are evaluated on how well they meet the plan's targets. Sometimes, this leads to forest-for-the-trees situations: it's not unusual for the plan's wider objectives to be thrown out the window in order to achieve an obscure data point.

'Widespread irregularities'

China's affordable housing initiative is a good example of this pattern. In 2010, the goal to build subsidised housing was a key initiative of the 12th five-year plan.

The specific goal called for 36 million units of subsidised housing to be built within five years. According to the official statistics, the plan was a success.

China's housing market has taken off in recent years

"In reality, we've already built more than 36 million units of subsidised housing in five years," explains Jiang Xuemei, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

"There was an even bigger process to renovate shanty towns. We aimed to renovate 4 million but in reality, we renovated 10 million of them."

But a closer look reveals a more complex picture.

In 2014, China's state auditor uncovered "widespread irregularities" in the affordable housing programme. Approximately $1.47bn (£958m) in funds was misappropriated to pay salaries, office expenses and to "invest in wealth management products", the auditing office discovered.

Some companies illegally obtained 485 million yuan ($77m, £50m) worth of subsidies to build housing that did not qualify under the scheme, including dormitories and offices.

A further 20,600 people were found to have used fake documents to obtain low-cost housing under the plan.

"Corruption does exist in some places," Ms Jiang notes. "The challenge now is to manage the current housing projects and make sure they are fully utilised."

Balancing the economy

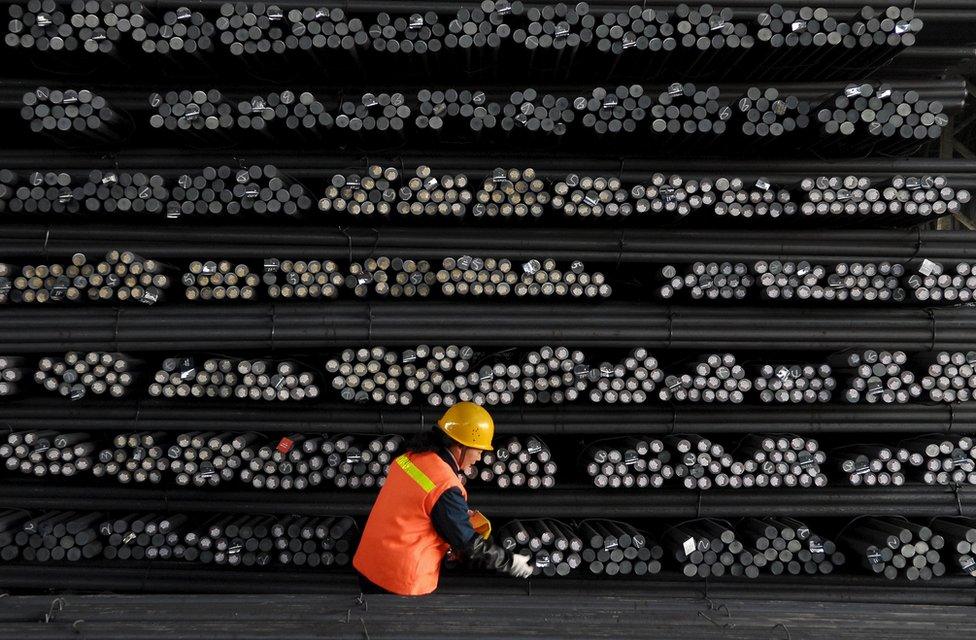

Attempts to steer the economy into a new direction formed another part of the last five year plan.

China's leaders have stated repeatedly they want to move away from a dependence on low-cost exports towards more sustainable growth that relies on the service sector, high-end manufacturing and domestic consumption.

Low-end manufacturing and exporting still powers China's economy

Did the government achieve its economic reform goals under the five year plan?

Technically, yes. Many of the economic targets in the plan appear to be on target.

"We've reached a preliminary goal to restructure our economy to focus more on the service industry," explains Chi Fulin, the director of the Chinese Institute of Reform and Development, a think-tank based in Hainan.

"The service industry now contributes more than 51% of our GDP growth, higher than we expected. Secondly, we've reached the goal of 7% economic growth and third, consumption became the main driver of our growth, accounting for 60% of the growth of GDP."

However, consumption has grown in part because the demand for exports has fallen due to the global economic downturn.

"The restructuring of our economy hasn't fully succeeded, the speed isn't fast enough and the service industry still plays a relatively small part in the economy," Mr Chi says.

"We still face difficulties. China is at a stage of development where we've nearly reached the end of the industrial revolution."

Relevance

Is the five year plan system still worth it? Is there a value in planning in such detail, so far in advance?

Chi Fulin thinks the plan's function has changed, giving it a new purpose.

"China's five year plans derive from the planned economy we had a long time ago," Mr Chi says. But now, he explains, "our plan has changed from a firm plan to an overall objective."

"We are focusing more on the predictions and strategy and shaking off the aspects of an old-fashioned planned economy. For example, when we set a target for a growth rate, we're only predicting a rate rather than deciding it."

This shift in thinking reflects a new breed of Chinese leaders: those who recognise that many aspects of China's development are simply beyond their control.

"In my opinion, the speed of our transformation hasn't met my expectations," Mr Chi says. "I think the difficulty we faced while restructuring our economy was much bigger than we ever imagined."

- Published30 October 2015