The 'Michelin curse' comes to Hong Kong

- Published

One customer who seems as keen on the dumplings as the Michelin judges

Winning recognition in the annual Michelin Guide is one of the most sought-after honours in the restaurant business.

But in Hong Kong, a city plagued by high rents, the accolade may bring unexpected challenges.

Just ask the owner of Kai Kai Dessert, which specialises in classic Cantonese desserts like steamed egg pudding, red bean soup with lotus seed, and papaya and white fungus soup.

Chiu Wai Yip, 58, told BBC News that just weeks after being featured in the Michelin guide in November, the shop's landlord more than doubled the rent from HK$100,000 ($12,900; £8,800) to HK$220,000 ($28,378; £19,400) a month.

What's more, the landlord wanted to halve the amount of space the eatery currently occupies.

"It's really too bad," Mr Chiu says. "After we were recognised by the guide, the owner raised the rent by a huge sum. So, we have no choice but to relocate. We have no other option really."

A loyal customer came to the aid of Chiu Wai Yip and his delicious desserts

The family-owned business has been an institution in the gourmet haven of Jordan for three decades.

Even in the middle of the afternoon, not a traditional time for dessert, every table at the eatery is occupied by customers slurping its delicately sweet creations.

Luckily for Mr Chiu, after hearing his plight, a regular customer came to his rescue.

In March, Kai Kai will move around the corner, where he will pay a cheaper rent of HK$90,000 per month.

Kai Kai is one of about two dozen street food eateries in Hong Kong featured in the Michelin guide for the first time.

The inclusion of such accessible, authentic local fare was praised by many food critics and bloggers, although, as often happens in the controversial foodie world, the exact choices were hotly debated.

But because all of them charge such low prices - a bowl of pudding at Kai Kai costs less than three US dollars - they are vulnerable to enormous rental increases, resulting in what some call the "Michelin curse".

Kai Kai is an institution in the foodie haven of Jordan

Another establishment similarly affected is Cheung Hing Kee, which specialises in Shanghai-style fried dumplings.

Called shengjianbao, they are moist on top and pan-fried to a golden brown crunchiness on the bottom.

Eating them takes some practice. If you're not careful, a mouthful of sticky, savoury pork broth will shoot out onto the unsuspecting diner.

An order of four dumplings, enough for a moderately hungry person, costs HK$28 ($3.60; £2.50).

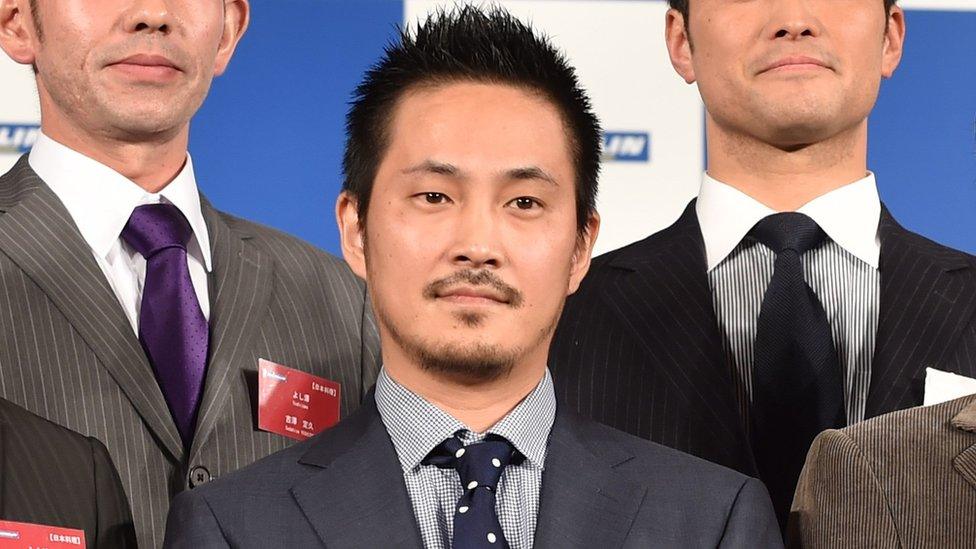

Owner Sun Kei, 50, and his business partner started the tiny eatery in the modest working-class neighbourhood of Tsuen Wan three years ago.

Both have family roots in Shanghai and wanted to bring the fried soup dumplings to Hong Kong.

Shengjianbao Shanghai dumplings - a feast for the stomach and the eyes

The former British colony, Mr Sun says, is quickly losing its culinary street culture because of high rental costs and rising salaries.

According to research from real estate firm Jones Lang Lasalle, rental prices among high street shops in Hong Kong have nearly doubled since the city was handed back to China in 1997.

Denis Ma, head of Hong Kong research for estate agency JLL, says he thinks the "Michelin curse" is a myth. He believes gentrification and changing demographics are to blame for sky-high rents.

Prices actually peaked in October 2014, and have been falling steadily since.

That has not helped Mr Sun, who started rental renewal negotiations with the landlord before being recognised by the Michelin guide.

After winning the honour, he says, the landlord's attitude hardened and he refused to budge from a 30% increase in monthly rent.

The dumplings had customers queuing up long before a certain French food guide arrived

"I don't blame Michelin for this," Mr Sun says. "To be honest, I don't really blame the landlord either. He has to make a living. He should be trying to get what he can."

"But the Hong Kong government has not done a good job in managing the rental market, leading many small and medium restaurants to close. Hong Kong used to be a food capital. Now, that glory is really fading. And its getting worse and worse."

He wants the government to reinstate a rent control policy that was abolished in 1998.

But even that policy had applied only to residential, not commercial, rentals.

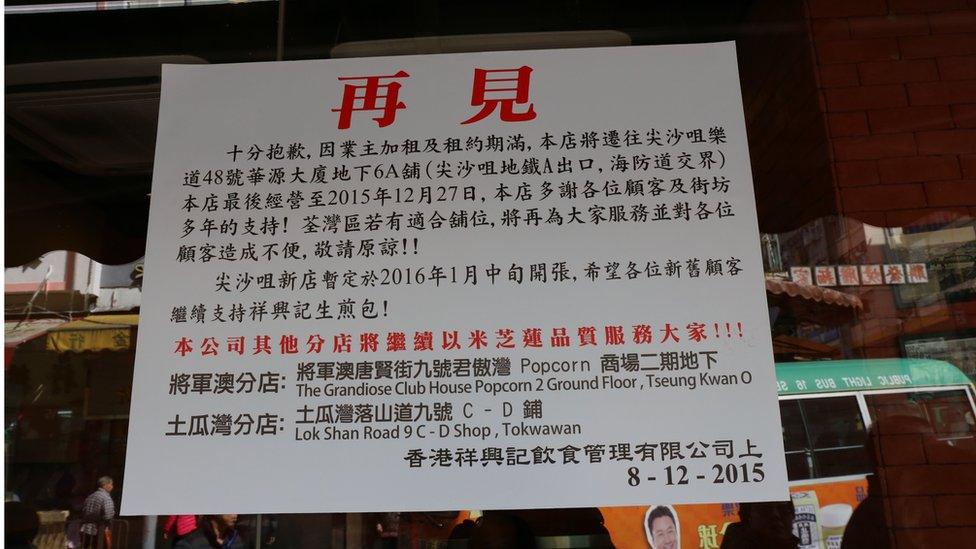

Buoyed by the Michelin recognition, Mr Sun plans to open a new branch of the eatery in the commercial district of Tsim Sha Tsui, which is popular with tourists and office workers.

But news of the move has angered many loyal customers.

They are sharing photos of the closing notice on their social media networks, decrying what they call "greedy landlords".

One of them, Crystal, says she feels like crying.

"There are many good restaurants in Tsuen Wan. That's why I still live here," she explains. "I think it's a real shame they're moving."

Moving location has been wrenching for restaurant owners and customers

Mr Sun says he is just as sad to be abandoning the neighbourhood that gave him his start as an entrepreneur.

"Of course it was great to be recognised by Michelin," he says. "It was public recognition of our team, our food and our service. It really encouraged us. But, of course, not everything resulting from that was positive."

He vows to return to Tsuen Wan as soon as he can find a new location.

Like the owner of Kai Kai Dessert, Mr Sun is realising that being featured by the Michelin guide has its downsides.

- Published4 December 2015

- Published2 December 2015