China's political propaganda gets a digital makeover

- Published

More than 3,000 representatives gather at the congress

China has been trying and failing for years to get its people, especially its young people, to care about its political system. Could it now be close to working out how to do just this?

Every March, the National People Congress, external (NPC), China's biggest annual political event, goes virtually unnoticed by the vast majority of the Chinese people.

But if you've ever been to China, you will notice the government's propaganda is installed everywhere, from Chang'an Avenue in the capital city of Beijing to the small rural alleyways.

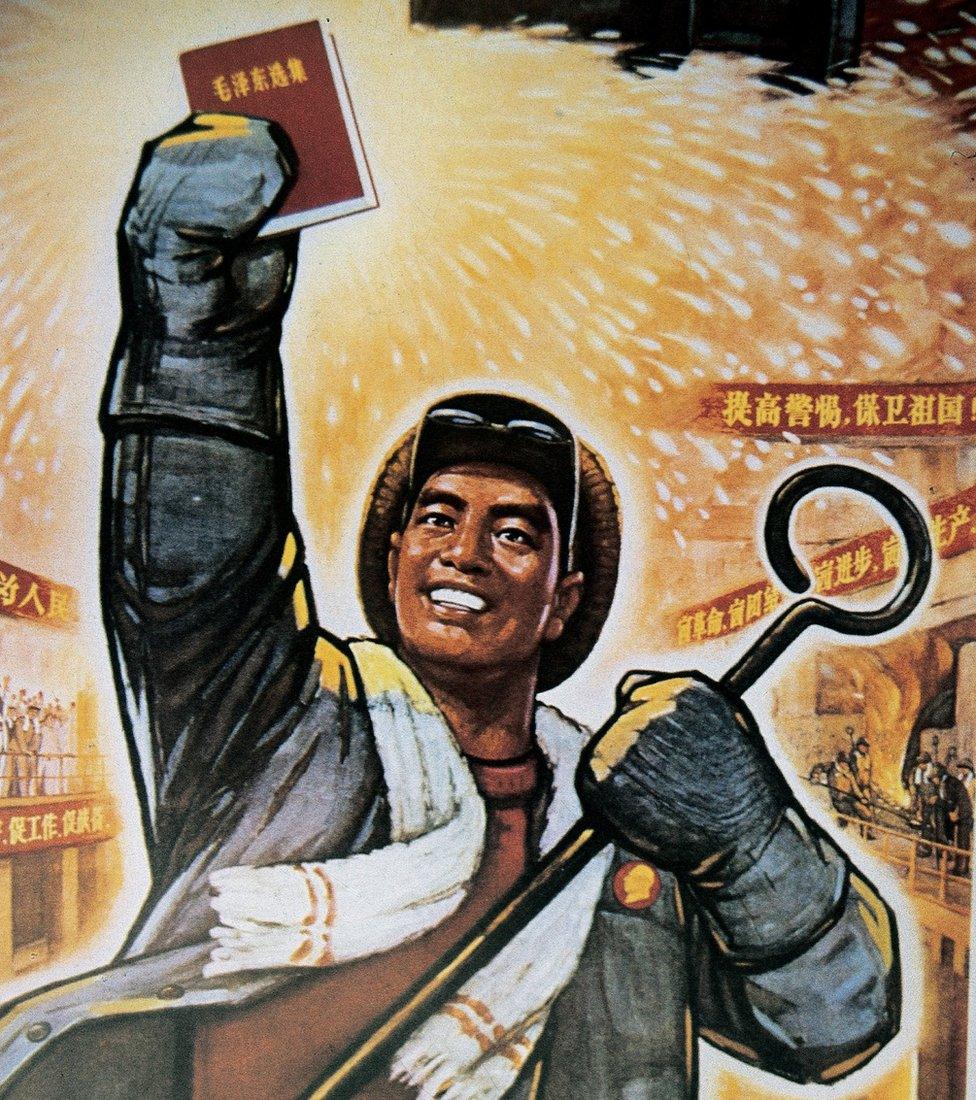

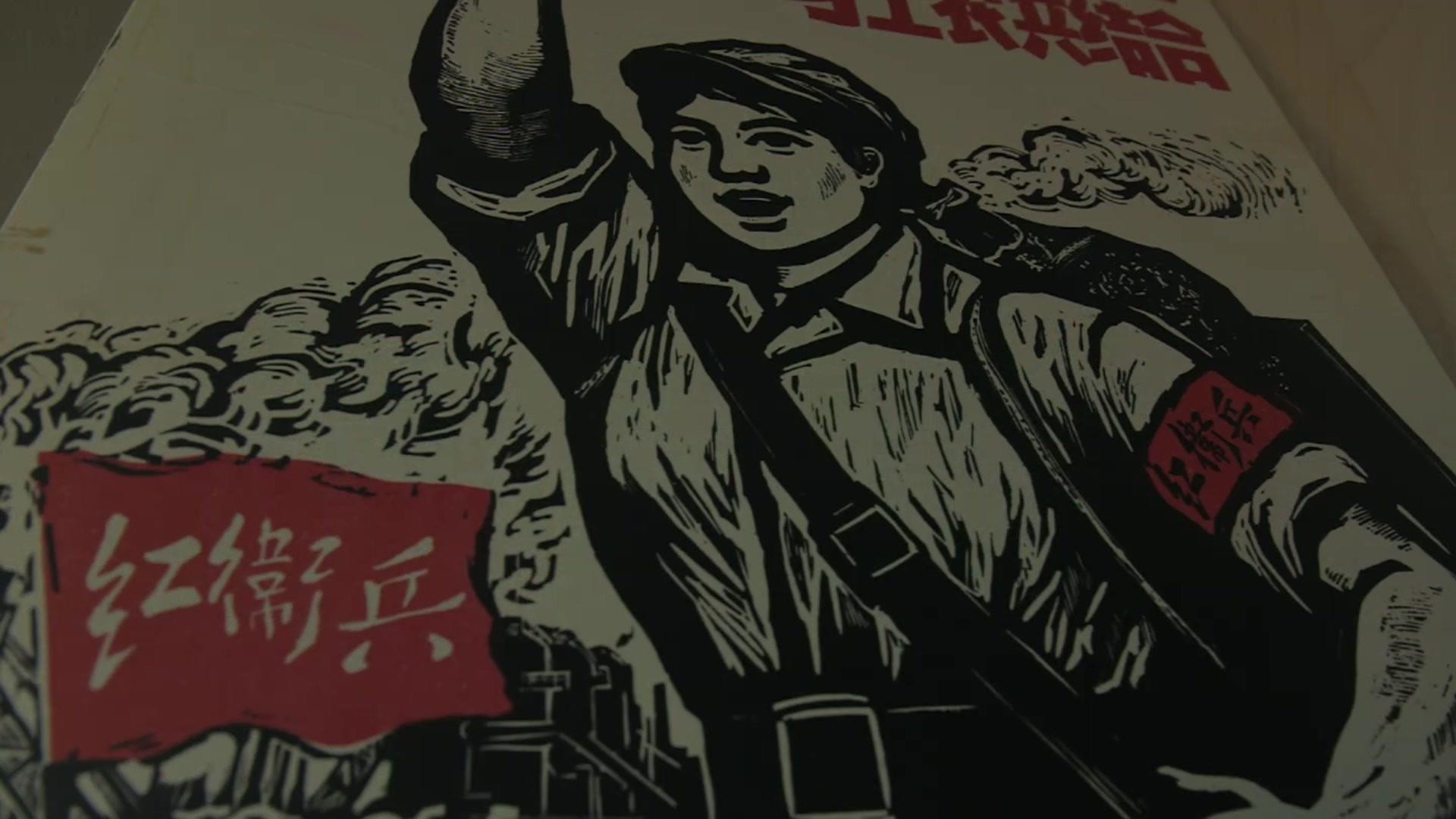

Party and productivity: the core messages remain much the same

Red posters with white ink writing, politicians' long and dry speeches and endless awkward slogans, the Communist Party of China has consistently delivered in spreading what some would see as monotonous political messages and doctrines.

But as the propaganda platform shifted from rice paper to LED screens, the government has developed new tricks.

One of its first big successes was the music video of "Shisanwu", the 13th Five-Year Plan, which came out in 2015. So how do you sell the idea of the 13th five-year social and economic development strategy to young people?

The Shisanwu music video was a major departure from traditional propaganda

An animated music video with a foreign band singing in English of course.

It became an instant hit on social media with young people talking about it, sharing it and even learning to sing it.

There are more such tactics being adopted this year. A rap song called "My Two Sessions, My Say", produced by the People's Daily, a Communist Party mouthpiece describes the grand scene as delegates of the National People's Congress and the Political Consultative Conference arrive with their people's agendas.

The People's Daily produced an unorthodox but colourful take on the rap genre

It has all the buzzwords, it discusses social problems like China's petitioners, government officials being lazy at work, but also suggests all grievances will be discussed and the people will get their answers. It dismisses the idea that the congress is just a rubber stamp political body.

"Wow, even the old school People's Daily starts to rap," is one response largely echoed in social media.

But others were not impressed.

"Not my delegates, not my congress. I never had my say."; "Who are these delegates? I didn't vote for them."

Tackling environmental issues is increasingly a propaganda theme: this LED screen in 2014 urged people in Beijing to help protect clean air

The Chinese State Council also released a series of newsy digital videos featuring people's wishes in the run-up to the congress.

They even interviewed carefully-chosen celebrities, such as Hu Weiwei, entrepreneur and founder of China's most successful shared electronic bikes and a viral sensation in China.

Ms Hu said she used to feel the government's NPC report were strange and distant. In another interview, the famous actor Ge You said he wants to hear about solutions to air pollution.

All these reflect the genuine concerns and feelings of ordinary people.

Alongside politicians like Premier Li Keqiang, coverage also included more unusual faces like entrepreneur Hu Weiwei, left, and actor Ge You

"I give full points to the PR team behind it," says one web user: "If the government had been talking to me like this, I would have listened."

The propaganda initiative has even stretched as far as a group on WeChat, China's most popular social media app.

WeChat is wildly popular in China

As soon as you enter the NPC chat invitation you are suddenly "in a group" with Premier Li Keqiang, government ministers as well as delegates.

It's all obviously simulated but the interaction eventually takes you a page where you witness a simulated conversation between yourself, other ordinary Chinese people and high ranking officials.

WeChat users are encouraged to engage with the state through the app

"Group chatting with state leaders. Such a cool idea.", "It felt so real. I like it," many have commented on social media.

"It's all fake. It's a reminder that we would never be able to have exchanges with the state leaders or the congress delegates directly like this," say the sceptics.

But no stone has been left unturned in this unprecedented campaign to reach the digital masses.

So even foreigners have been recruited to help, possibly in the hope that foreign faces will help engage a foreign audience too.

Foreigners are increasingly appearing in Chinese propaganda

In one China Daily video explainer, a British man called Greg turns into a miniature doll on an office table. He walks through a calendar, Xi Jinping's book The Governance of China, as he explains the congress.

Critics say it's the same old propaganda, just on new platforms.

But they show a desire to innovate on the part of the government and state-run media and engage the public on the platforms where they know people prize such innovation.

They can claim success in one respect: at the very least they are getting young people to talk about the congress.

Five years ago this was not happening.

Delegates from across China gather in Beijing for the NPC

- Published13 March 2017

- Published30 June 2016

- Published27 October 2015

- Published15 May 2016

- Published26 August 2016

- Published14 January 2013